Mgzavrebi, Waltz

Tell us a bit about your route into filmmaking. Was it something that had interested you from a young age?

I didn’t plan to be a film director, but after completing my degree in acting and directing at the theatre institute, I wanted to change my life and explore something new. Writing stories has been a passion of mine since my youth, so I decided to try my hand at screenwriting. As I delved deeper into the craft, I saw each music video as a small film with a story and dramatic structure. After creating a few short films, I wanted to explore the medium of music videos. Instead of relying on the typical approach of having an artist sing against a particular background, I aimed to tell a story more innovatively. Although this approach was unpopular for music videos in the past, I was inspired by pioneering experimenters such as Unkle, Radiohead, and Massive Attack, who created videos directed by Jonathan Glazer, Spike Jonze, and others.

I adopted a unique approach to creating video clips using a visual sequence with a dramatic structure and musical accompaniment, similar to silent films. This method served as a learning experience as I gradually developed my craft and began writing longer forms of content. As I gained more experience in the industry with clips and advertising, I became familiar with the workings of the movie business and the structure of film production. I learned how to work with tight budget restrictions and use the approach of clips as a form of silent cinema to my advantage. This ultimately led me to my first feature film, The Execution.

I realized I had chosen the wrong profession when I enrolled in a theatre university. As a result, I started exploring other industries. Writing had always been my passion, so I shifted my focus to screenwriting. After spending considerable time working on various materials, I strongly desired to produce and direct my own written works.

Later, at over 30, I plucked up the courage to call myself a director and continued to study. This profession has a peculiarity – it does not have an endpoint. There is always a feeling that you are looking at the horizon, seeing some island, and when you swim to it, you need to formulate a new goal, which is again hiding behind the horizon. And you keep moving. The profession of a director involves an endless journey throughout one’s life. In the process, you formulate points where you need to halt and spend the night – there are periods when you can realize that you have come some way, but in no case admit that this is your endpoint. Unlike many others, this profession has no finish line.

Mgzavrebi, Waltz

Your latest music video/short film for Mgzavrebi, Waltz, is both a moving and original tribute to your Georgian roots, and a poetic exploration of love, loss and family ties. What was the initial inspiration behind this passion project – was it a topic you’d wanted to explore for a while, and were just waiting for the right vehicle?

I am an ethnic Georgian, so I have always wanted to collaborate with Georgian artists. Three years ago, Gigi Dedalamazishvil, the band leader of Mgzavrebi, wrote me an offer to work together. We met in person in January 2022 in Tbilisi at a private screening of my film The Execution. Gigi sent me Waltz. After listening to the track, but not knowing the meaning of the lyrics in Georgian, I wrote a script that completely coincides with song’s message. It’s about Gigi’s first sense of loss. He tried to express the feelings he encountered at 16 and 17 when his grandmother died. It’s a song about losing a loved one, a quiet dance with oneself, or, more accurately, a kindred departed soul. Although the key in the music is the lullaby motif that Gigi’s grandmother sang to him as a child, I believe it works universally with any listener or native speaker of any language.

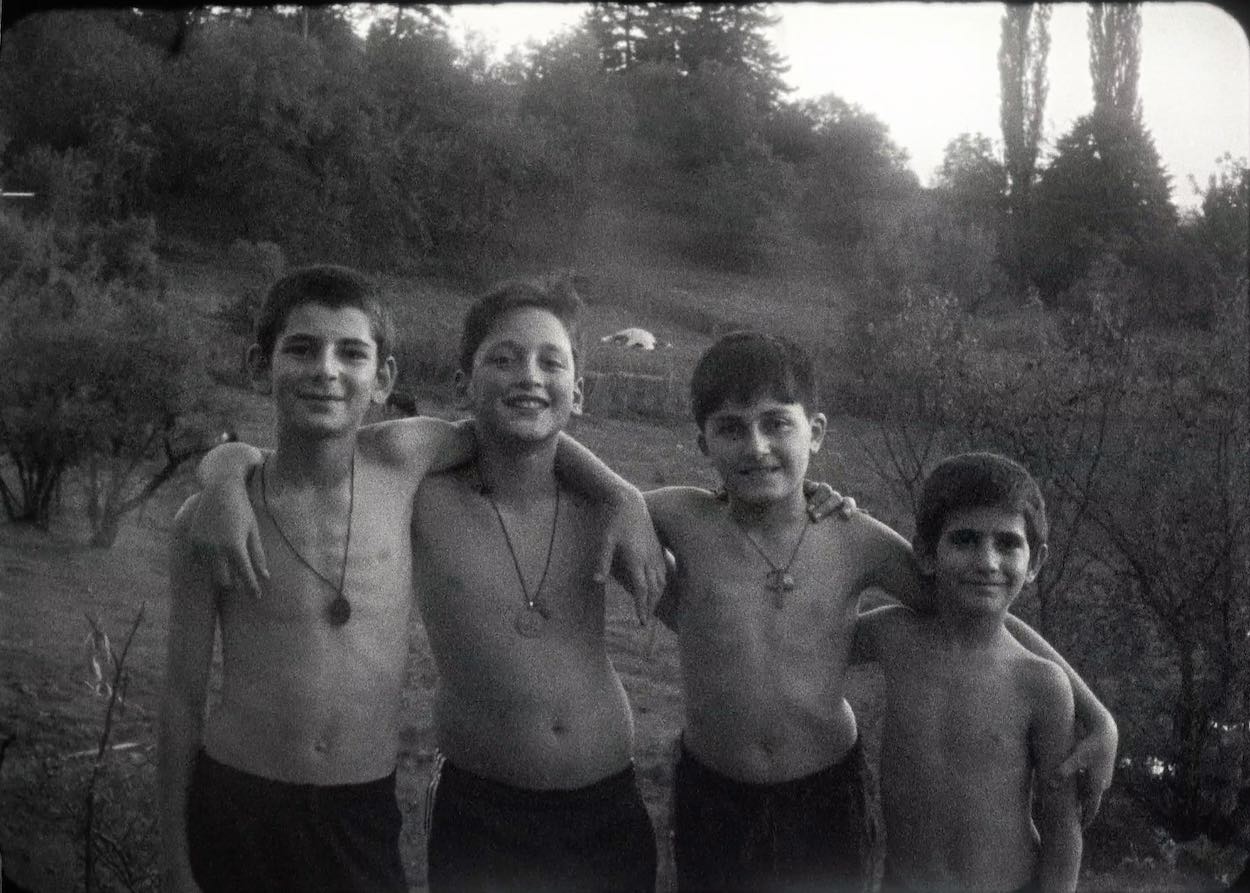

I spent my childhood in a Georgian village, influenced by certain context and traditions. It was important for me to take a journey into the past in order to understand my identity and, above all, to have an internal talk with my departed loved ones. I wanted to imagine how and where relatives who are no longer around live, to see them and to know that they are good now. This is such a kaleidoscope in my mind, fragments of the warmest memories from childhood in Georgia: our hazel tree groves; a pond where we fished never seems to be empty; an old aluminium washbasin in the yard, filled with ice water in the morning. This is a time for me in which it is safe and happy. From such precious fragments, a feeling of inner warmth is formed, which is always by your side when you turn to these memories.

Mgzavrebi, Waltz

The film was a year in the making, and shooting took you to some remote locations in Georgia – what did you learn about yourself during the process, both as a filmmaker and personally, in terms of your cultural heritage?

My guide to preserving values and love for Georgia is my father. Since childhood, he never tired of repeating to me: you must remember who you are, your relatives, where you come from – and respect and appreciate it. Thanks to my father, I was able to keep some connection. But at a conscious age, I began to show interest in Georgia and tried to visit it more often. I became acquainted with Georgian art and culture.

I have an innate understanding of certain Georgian behaviours, possibly due to some genetic predisposition. It feels like a unique Georgian code is imprinted upon me at birth, becoming increasingly apparent. To gain a deeper understanding of Georgia, I started filming here. Through capturing the world around me in my work, I have discovered a unique way of experiencing the country’s history and cultural contexts. The more I visited Tbilisi, the more I got the feeling of a place where I feel calm and harmonious. Here I began to feel a sense of home. Georgia reminds me of my childhood memories spent with my grandmother and parents. I am filled with a sense of security and comfort each time I return. This is where I spent my formative years, and it holds countless cherished memories and emotions that will stay with me forever.

As I’ve spent more time here over the past five years, I have gained a better understanding of the context and issues that are currently relevant to Georgia’s development. It’s fascinating how even without knowing the specific circumstances of the country’s current situation, one can still intuitively grasp the context. I have realized this is my home, where I feel most comfortable. However, I do not want to confine myself to living in just one country. I prefer to reside wherever I want to at the moment. Unfortunately, people are often categorized by their nationality. Nevertheless, I value individuals based on their character and their role in my life, not their race. Their nationality does not influence my love for people, as it is my least important factor.

As I continue to explore Georgia, I am discovering this country more and more and feel the need to talk about it, so I want to make a full-length Georgian film. After all, the only thing I can do is confess my feelings by doing it through the cinema. That’s why I made up Waltz, my little movie about big love for this place. And while that may not sound like the best ‘toast’, it’s okay. Anyone who reads this will forgive me.

I find Georgian cinema and culture incredibly emotional and filled with love. The country is a space where people display philanthropy and compassion. One of the most remarkable things I have observed in Georgian films is how the filmmakers strive to understand and forgive even the most unpleasant characters. No matter how disgusting the hero is, the author still tries to accept, forgive, or let him go.

Mgzavrebi, Waltz

The parallel storyline, which converges at the end of the film, is beautifully realised both through the editing and the use of two kinds of film to represent the past and current threads – can you talk us through the choice of film and cameras, and how you developed the edit?

Due to the project’s modest budget, we initially had a clear limit — 15 cans of film for the entire movie. We divided the filming period into two blocks. A black-and-white documentary block filmed in mountain villages was limited to three cans of film. The main acting colour block was filmed in Tbilisi and was limited to 10-12 cans.

We filmed in the highland villages of Racha and Bakhmaro. The footage was collected bit by bit, with a minimum daily output. I was limited by three cans of film for this part, and I did not have the opportunity to shoot several takes. Before clicking the record, I had to decide what to shoot.

We were also limited in time: from day to day, the onset of seasonal cold was expected, and the snow should come, so the villagers had to leave the village for several months and go down to the area below, where they usually spent winter. It’s a miracle that we managed to film this fragile timelessness. Therefore, thirty minutes of this footage is so precious. Of the thirty minutes I got in the mountains, I selected five-seven minutes for editing.

We had a specific task: to distinguish between two worlds visually. I also built the contrast between the two worlds on the technical features of the used cameras.

We began shooting with a Scoopic, but it broke down quickly, so we continued with a Bolex from the 1960s, giving us the documentary effect we wanted. Thanks to flaws, some marriage of image and light, this camera creates a sense of chronicle. I wanted to achieve the impression that this picture was taken 100 years ago. As if this material was not filmed by us and not now, like these are shots of old chronicles, which seemed to be found somewhere in the Georgian archive. Bolex is an old camera with certain bugs and difficulties. It was wound up manually using a rotating lever. You can only film for 30 seconds, then the shooting stops.

The modern storyline was filmed on Arriflex 416, which gives a completely different image — cleaner and smoother. There was also a technical problem. We also used vintage optics for this camera, but it failed. It turned out that the wide lens was defective. We didn’t do a timely test, and we were punished for the laziness that the film crew once showed. Part of the general footage was filmed a little bit blurred, unsharply. And some of the shots had to be re-shot. But, as is usually the case in such situations, the retakes only improved our story.

The visually contrasting junction of these frames reveals all the precious textures that Georgia is rich in.

Mgzavrebi, Waltz

One of the most powerful themes in the film is the sense of family and history repeating itself throughout the generations, which are bound together across time and space. Is reincarnation something you can relate to personally?

This is the eternal theme of the conflict of generations. And I am no exception; with years, I began to feel that I was moving away from my culture, my past. Urbanisation and new ethics are changing the speed and focus of perception of the modern world. It is essential to remember where you are from and who you are; honour your culture because it has shaped you as a person. You should not deny the positive features of progress; you need to keep up with it, especially if it offers humanistic ideas. But for me, it was important to return to my roots, the past. Remember who I am. Perhaps to resolve some issues related to childhood. And, of course, to confess my love to my grandparents; to give them the respect they deserve.

Waltz has overcome many obstacles. When the war began, everything became indifferent, including the project. Everything around and life itself lost its meaning. Meanings faded away. But over time, I realised that this work has an important mission — to remind us about the value of human life. It has become so important to realise that life is so fragile. You can’t know how your day will end — maybe it will be your last. And suddenly, I realised that most of all, I would like to imagine how our departed loved ones live, to see them. I wanted to imagine the place where they would now be — and feel that they were no worse than here, and maybe even better.

I have a rather gloomy, pessimistic view of the world. But this year, I denied myself that opportunity. It was essential for me to start with myself and change my view of the world, to find the light that we need today more than ever. When I watched Waltz as a spectator, I felt that an inexhaustible supply of light remained inside. I experienced a feeling of purification. I won’t lie, I cried. And I appreciate the fact that there is a similar response from the audience. Many comments and posts sincerely share personal family stories, memories, and feelings. We dedicated our film to our loved ones; the audience dedicates it to theirs. It is precious to me.

Mgzavrebi, Waltz

Waltz feels like a huge departure, stylistically and tonally, from previous work such as Leningrad Gold, Christmas on the Moon and Husky Judas, which are all pretty NSFW and heavy on violence, gore and horror. And it feels different again from your animated political polemic, Burn. In fact, there’s such a wide variety of styles and techniques within your work, it’s hard to see a signature aesthetic – are you a filmmaker who enjoys experimenting and variety? Is there a particular genre you’re drawn to, or does the creative concept/brief dictate the style?

In each new project, I challenge myself to come up with something that surprises me first. I see music videos genre as a laboratory where I can experiment with new tools and techniques that were once foreign to me. Each project brings a new set of challenges that I and my creative team must face. Sticking to a familiar style and path is not appealing to me. A director’s style is not defined by just the tools they use but rather the themes that they explore. My stories may have similar elements, but I always strive to find new tools, creative techniques, and experiments to tell a narrative in a fresh and unique way.

Since the outbreak of war, a full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, my life has changed drastically. I underwent a reassessment of values and decided to shift my focus from violence-related topics to something entirely different. My goal was to remind myself and others about the importance of human life. This may seem like a cliche and a well-known truth, but amidst this war and the numerous deaths, it is crucial to speak up as often as possible to emphasize the most important things.

You tend to explore and experiment with various tools to showcase your versatility when young. As you grow older, you become more restrained and focused on the meaning behind your work. Waltz was a technical experiment for me, where I deliberately stepped out of my comfort zone and challenged myself by using non-professional actors, a static camera, and many restrictions. Despite these limitations, I aimed to capture the true beauty of life and elevate its everyday moments to poetry. For my team, Waltz is a tribute to life and the people we captured through our lens.

This work has become saving, therapeutic, and healing for our team. Because it determined the meaning of our existence for a year. When death has become a part of your life, I would like to find a light in this darkness, salvation. It is easy to find yourself at the very bottom of this funnel of darkness. Therefore, the whole team set off on this beautiful journey. And now, when it comes to an end, we miss each other, and this wonderful period. The reality is so arranged that each of us needs to continue to move on, but this wonderful production period will forever remain with us. Each of us left a piece of ourselves and even something more. Each of us danced the same waltz with our beloved departed ones.

Monetochka, Burn

Much of your work carries political messages, both overt and implicit: Burn, for example examines the pitfalls of propaganda and the way we’ve become disengaged, uninterested bystanders at a time when we should be taking action and provoking change in the world. Do you consider yourself a political filmmaker, and do you feel a responsibility to effect change through film?

Living in a certain context is crucial for all of us to understand. As a director, I mirror the reality around me and cannot ignore the situation in which people live, including in Russia. My father is from Georgia, my mother is from Ukraine, and I have spent most of my life in Russia, so I cannot ignore what is happening around. Before the war, my creative expressions had certain risks. And new levels of risks arise now – they are incomparably higher. In Russia today, making any statement can result in a fine, and many people are being imprisoned. It has become a terrifying habit to watch daily reports of people being sent to jail. This is disgusting and terrible, and this is a new reality.

I do not see myself as a politically motivated director. I respond to the reality I encounter. It seems odd to me to talk about trivial or secondary issues when there are monstrous things happening around us. However, I have certain requirements for myself: the most crucial statement can only be made in context. The director’s conflict with the environment gives birth to topics and opportunities for discussion. I cannot always provide a solution to a problem, but I can initiate a conversation so that society can pay attention and express its point of view on the topic. I don’t expect viewers to agree with me when they watch my work. It is important to me that a dialogue takes place between me and the viewer through the film.

Leningrad, Gold

Are there any topics or themes you are keen to explore – or revisit – in future projects? And do you have any exciting work in the pipeline at the moment?

I am currently involved in the pre-production of two feature-length films.

One of my long-term goals is to create a film in the Georgian language. I am currently working on it, and it brings me great joy. It will be a tragicomedy. The idea for the film originated from our short film Waltz. My co-author Irakli Solomonashvili, and I have completed a detailed plan for the movie, including each episode of the story. Seeing the roadmap of the movie and the sequence of scenes, I felt that the film had finally come together. My partner Erekle Rodonaya and I plan to start filming next year.

The main thing for me now is that we are making our dreams come true in a team of very dedicated people.

Interview by Selena Schleh

INFO:

Lado Kvataniya’s website

Daddy’s Film website

Stereotactic website

@ladokvataniya

@daddys.film

@stereotactic