What was the initial brief and what were the early conversations about?

The brand has done a lot of research into African surf culture with their previous book project AFROSURF. Peet Peinaar, the creative director of Mami Wata, has a deep understanding of the subject which fuels his unique and powerful creative outputs, so the initial conversations were informed and exciting, overflowing with creative ideas, a beautiful way for a project to start.

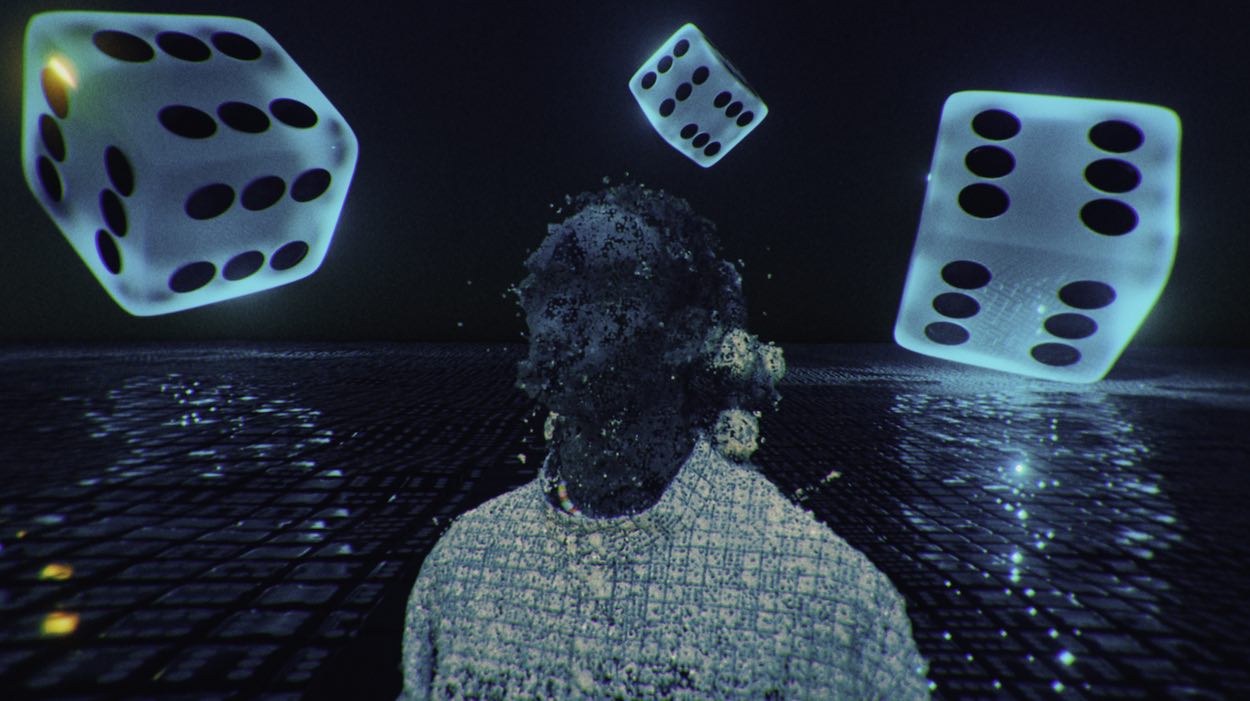

The film’s story was inspired by one of the interviews in the book. So the core story of the film was quite clear in the initial brief – animistic elements of luck drawing a surfer to the water to find his freedom. But there was lots of creative freedom on how to bring this story to life; what the journey looked liked etc.

These smaller, less commercial projects are fuelled by creativity, but it’s about being clever production-wise to make sure every decision maximises the end product.

The biggest decision early on was to make the whole shoot happen in Senegal, and create a strong treatment that could get collaborators excited to get on board.

Getting Jo Barber to produce the job early on was crucial in allowing us to make these key production decisions, to help maximise the creativity.

An animist? Can you explain please… and tell us about the lead character Damme Samb.

Animism was a new concept to me when I received the brief, but as soon as I delved into it, I realised that it’s not as foreign as I expected. I think most human beings can connect to the term in some way, “the belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence”. Just maybe in my world I never had a word so directly for it. One thing that is important, is that it is not a religion, it lives alongside religion, as a separate belief system.

Some things you plan really hard for, and some things just happen and you are VERY grateful. Casting Damme was possibly the best thing we could have never planned for. We spent quite some time in pre-production, doing castings remotely with other Senegalese surfers who the brand had connections with through the AFROSURF project.

Damme was a surprise, the underwater camera op, Calvin Thompson had worked with him previously and said he had a wonderful energy, and when we arrived in Dakar we got to experience it for ourselves.

A few lucky things fell into place, and Damme joined us on this adventure. Although he had been featured in a surfing film before, this was his first time really performing in front of a camera on land.

The language barrier was tough, but together we got into a beautiful flow and an understanding of the energy of each scene: he felt natural and powerful at the same time. Damme lives with his family in Dakar and is a surfing instructor by day. The close up portraits in the blue room are done in his bedroom and the rooftop bubble shot is also connected to his family home.

We love your use of vfx and animation at the appropriate moments. Did you work closely with the brand’s creative director, Peet Peinaar, developing the visual narrative? And to what extent did you have the storyline fixed in pre-production?

Thank you, the surreal element was very important to push from the start. We never for a second wanted the film to feel like a pure documentary, Peet was clear about that. Their previous film four years ago (see here) was more in that aesthetic and this time it was to push into a new territory.

In the original brief Peet had ideas of surreal vfx moments, which we developed together, and then with the introduction of Gavin Coetzee into the team, Gavin really pushed them to the next level. The animation was handled in-house under Peet’s supervision. He also created the distinctive eye motifs plotted throughout the film.

The storyline was in some way very fixed, but with the freedom to completely adapt when we arrived in Dakar. We had reached out to people, scouted locations via google maps and online research, and were very excited about what we found, but we knew as soon as we arrived more exciting things might reveal themselves and we wanted to stay open to them.

I wish my more commercial projects could be more like this, and it’s something I would like to try and introduce more into my workflow. Plan plan plan, but then allow a freedom to shift if a better opportunity arises, and not get too fixated on what you thought was the best solution in pre-production.

You live in Capetown (and occasionally Berlin) – had you been to Senegal before the brief came in?

I’ve actually just arrived in Berlin now as I write this.

I had never been to Senegal, but instantly reached out to some friends who had, and received an overwhelming positive response about the place and the people. We also were connected to a surf photographer in Dakar via the brand and had calls with her, to discuss production resources that side etc.

Jo the producer had worked there before, which was great, so she was already connected to a great fixer who was instrumental in the success of the film. Meissa who owns Senegal Fixers, really embraced the project. I think sometimes fixers can just be there to provide what is asked for but Meissa was more creative, trying to understand what was needed then providing the correct solution even if it was different to our initial thoughts. It’s always special when people connect to a job personally which I felt was very strong in this production.

What was your process for scouting the locations?

Once we had decided on Dakar as the city for the film, it was a full-on internet attack. We luckily had some weeks to prep, so it was sort of a constant process of exploring Dakar virtually, google maps becoming our best friend. Although the story required certain locations, we wanted to see what extra the city added to the story that we could never have scripted, and I think one of my favourite locations was found like this. The room where the dice manifests is such a special location, that was never scripted but once we saw it we knew we had to write it in. As soon as we arrived we physically scouted the list of potential locations, and had to quickly come up with a final plan, and adapt our story and shooting schedule accordingly. It became a very fluid and instinctive process.

Did you spend quite a bit of time in Senegal filming and what were the main challenges of shooting there? Did you take a crew with you from Capetown?

We were there for nine days in total, which is something we worked hard to make happen. It was difficult to predict how long we would need but we knew the more time we had there the more unique opportunities would open themselves to us. It ended up being the perfect amount of time. Of course a few more days would have been nice, but I think that would always be the case. Nine days gave us enough time to explore, be inspired, and then action. Senegal doesn’t have a strong local film industry, so hero equipment was all brought from South Africa. The DoP Deon van Zyl created a very small camera set up, so we could be nimble and non-intrusive, which was key when working with such a hit crew.

HOD’s were all brought with us from South Africa, well except Deon who flew from London where he had recently relocated. (London is lucky to have him.) But our approach from the start was to have a small team of five, who were multifaceted, HOD but team players who would cross over departments if help was needed. It was a very collaborative, and exciting nine days.

How did you find directing the large crowd scenes?

This was one of the more stressful days of the shoot, but the stress was eased as it was largely guided by the advice of the fixer, especially on the areas and times we chose to shoot. We had some control, but a lot of it was also about working in environments we knew we could fit in, and not disrupt too much. So that a small intermittent lock off gave us great production value. A lot of the street scenes are shot in an area the fixer is very connected to and it was easy to negotiate and coordinate with the community. In the end it was all very smooth and we just had to be flexible and go with the flow, which sometimes is counter intuitive to our normal film-making mindset but very rewarding when you open up to it.

Was it always perfect weather conditions?

Far from it, weather was actually one of the biggest hurdles. With any surf related film, we knew getting the best waves would be tricky and out of our control, so we would have to allow ourselves as many surf sessions as possible. What we didn’t foresee was the water temperature changing drastically during the week we were there. This meant that surfing without a wetsuit became increasingly tough as the water temp dropped. Damme trooped on but it meant short sessions with large breaks to try and get his core temp up again. Again so grateful to have Damme with us on this project, he pushed on and on, building an instant trust that helped us through some stressful moments.

Being a small brand we’re assuming there were budget and time constraints – how did this impact on your production?

Of course it was very tight, and it affected production on every level. I’m very grateful for Stink and Giant films who fully backed me on this project. It’s of course them who take the biggest risk, but it was through joint production where we were able to think collectively and overcome the hurdles when you try to make something of substance with very little.

We fortunately did have some time to make this, which when working with such talented people is key, as they are all busy. We had to try and fit this in between their bigger commercial jobs. Xander Vander the editor and I worked through the end of year break, squeezing in any days we could.

A lot of making is about creating a final product you are proud of, which I am in this film. But sometimes there is deeper magic in the process of making, and for me this was one of those projects. Coming off a tough few months personally, I saw this project as something I could sink my soul into and in the process it gave me back far more than I could have imagined.

Represented by: