You seem to have been a bit of a creative polymath as a kid, judging by your bio – what drew you down the path of directing?

There were lots of ridiculous things I wanted to be growing up, but director was not on the list. However, I remember a point pretty young when it suddenly felt like I was supposed to make movies. Like a baffling and inexplicable knowing. Where I grew up, kids don’t make movies. If your dad worked heating and cooling like mine, you grew up on job sites. So it was a funny thing, this knowing. Like an odd sense of purpose that somehow smuggled its way in my skull.

Now, of course, no one in their right mind was going to let me direct anything at 15, but from what I could tell directors needed to know how to work with actors, and so acting became the ticket. I got into theatre, playwriting, the art of rehearsal. Fell in love with scene work, character development, dialogue and dramaturgy. What good fiction stands to offer its audience often comes in the shape of its characters, and the stage teaches you that. Theatre is still one of the best places to discover the time-tested pillars of storytelling.

You dropped out of film school aged 18, but continued to make films – how do you think that mix of training and independence has shaped your approach and aesthetic?

I say this with a bit of a wink, but I’d describe my aesthetic as hungry. Hungry and clinically obsessive. For me, ‘dropping out of film school’ was more like getting kicked out for being a broke ass kid who couldn’t pay tuition after God visited my Nana in a dream and told her not to co-sign my loan. That may sound salty, but my Nan‘s an incredible first generation Irishwoman and the Irish in me found it hilarious. And in a weird way I understood. You gotta trust your instincts.

I remember reading a Seneca quote around that time that said, “I count you misfortunate because you have never been misfortunate,” which became a sort of mantra for me. My friends at the school kept up the classwork while I worked at the YMCA and lived on couches. Being forced to drop out was an early lesson in the art of turning bad news into blessings. That’s the aesthetic of hungry. Before the school year was out, I’d written a handful of scripts and chased down a local producer to give notes on one called The Lost & Found Shop. That evening changed my life. His production company ended up giving us a bonafide Make-A-Wish package of film equipment – RED cameras, Master Prime lenses, two trucks of lighting gear, you name it. Which at the time felt like being accepted into Harvard.

These days I plan meticulously, to a point that feels like mitigating a cognitive disorder, but I’m always leaning into the obstacles, the curveballs. As a director you gotta have your ducks in a row, but it helps if you enjoy the hurricane – the moments where everything that matters is tossed to the storm. Looking back I’d say getting bounced from film school was probably one of the best things that happened to me. Whatever God said to my Nana in that dream, I’m forever grateful.

Let’s talk about your most recent short film, enough., with artist Nathan Nzanga. You met through Prodigy Camp – an intensive camp for young filmmakers and songwriters. What were your first impressions and what was it about his music that inspired you to want to create a film?

My first impression of Nate was that when you put a mic in his hand, he’s playing to a stadium no matter where he’s at. That’s an extraordinary quality. When I heard his new track, I was impressed by every aspect of it. I admired how he balanced nuance and compassion with indignation and righteous anger. For a young Black man in the summer of 2020, it was brave to say things he knew could piss off allies — let alone friends across the political divide. I have deep respect for artists attempting to strike those near-impossible balances. I wanted to make sure that whatever film came out of our collaboration did justice to his songs, and honoured the care he put into their construction.

What were the logistical challenges of using real footage of Nzanga shot over 10 years? There must have been a huge amount to sift through…

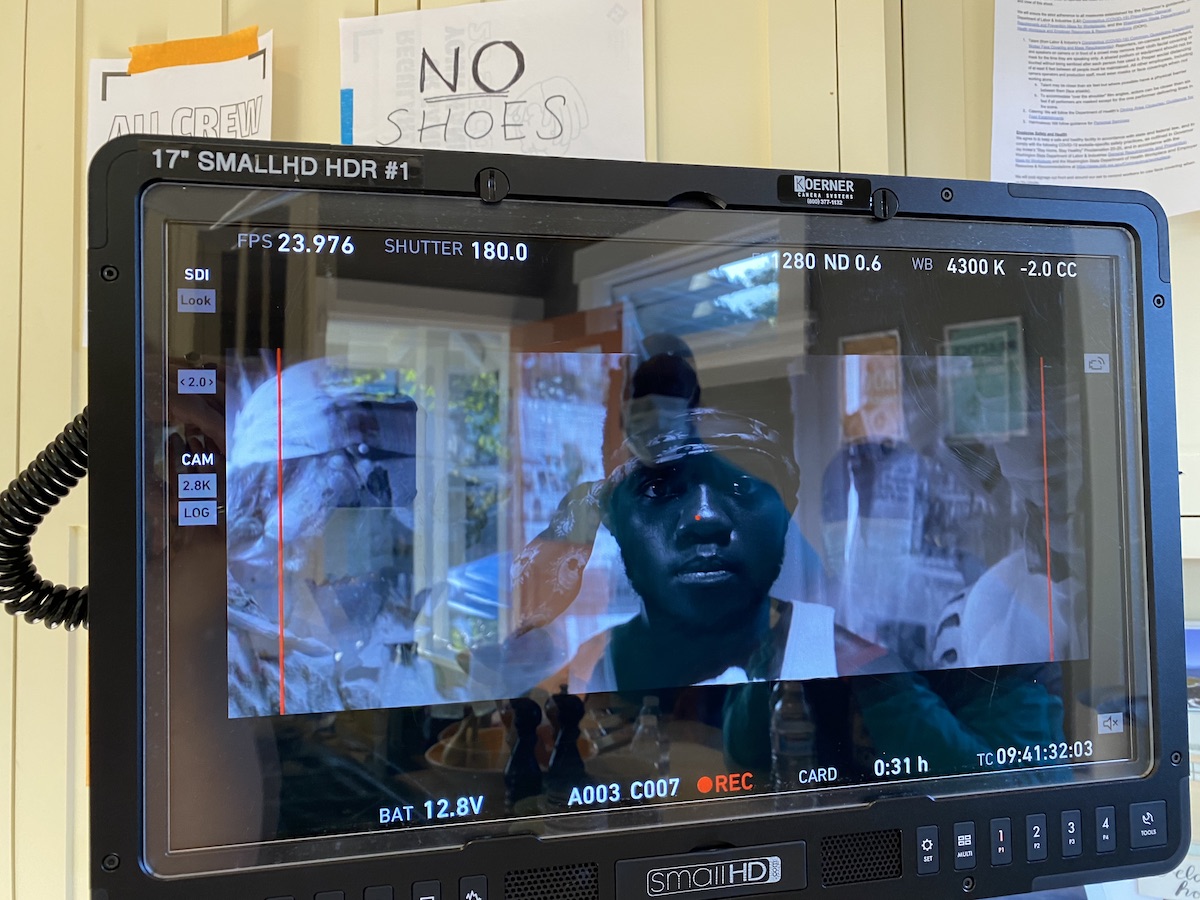

There was a huge amount to sift through. Ten hours, maybe more. No one had ever gone through it either, which isn’t abnormal for The 5000 Days Project. Typically the archival footage is turned over to each kid once they reach adulthood and complete their last interview, like having a video journal to look back on the rest of your life. I was the first person to go through Nate’s, but filtering down exactly what we would use required time we didn’t have. The shoot had an outrageous schedule, only two full shoot days on an eyebrow-raising budget. Stack that alongside the overarching political sensitivity, a narrative built on dream logic and the film’s genre-bending aspects and you’ve got a lot of moving pieces. So when it came to the interviews, my approach was to block out places in the structure where Nate’s interviews could interweave with the narrative. As a director you need to know the vision, but you also need to listen, especially with a story like Nate’s. Having a decade of documentaries under my belt definitely helped the process of sorting what should be firm and what should stay flexible.

How did you approach the edit? Did the story arc change much?

The arc didn’t change much. The way each chapter unfolds was being revised daily based on production needs and conversations between myself and Nate, but the big picture we locked in on. I did the first assembly in a few days and tagged in my long-time collaborator Nick Pezzillo to edit the interview sections — the intro and outro, as well as improving the overall cut. He’s edited a lot of hip-hop videos as well as social justice projects, so beyond his natural story talent Nick understood the material on a deeper level. His contribution was significant.

The Seattle anti-racism protests were ongoing during filming, that must have brought a very real and raw dimension to the project…

It did. Production didn’t cross paths with the protests directly, but the electricity was in the air. Seattle has a sort of sacred punk attitude when it comes to protests. They treat May Day like Dallas treats the 4th of July. We could have been out marching with them, and many of us had, but Nate and I knew this film was about the long game. What happens when people move on to the next thing? What stories are we taking out of this moment? How do we keep learning from it going forward?

As for locations, it took a month to get permits in the city due to COVID restrictions, and even those got revoked. We had to go outside Seattle, where we weren’t particularly shocked to discover that no officers would show up for our permits, which in one case left us scrambling for new locations on the day. Stir in the first-degree malarkey of trying to find a saintly human being willing to give free rein over their home during a global pandemic and the whole location-hunting saga felt something like playing whack-a-mole with a goose feather.

There was a huge amount of local support for the project, with people volunteering their time as cast and crew, and donating film equipment – why do you think it resonated so much with the local community?

Honestly, we didn’t have a chance without that support. The community made the impossible possible. There’s the obvious urgency to Nate’s story, but I think moral obligation is less effective when creating art than love, passion and inspiration. More than anything people just love Nate. I don’t think he has an enemy in the world. And it’s good music. Seattle knows good music. I’d also add that the Prodigy Camp is one of the most extraordinary communities of people I’ve met. I mean for all intents and purposes enough. is a summer camp video. The production company in the credits is the camp. Anyone who knows the camp knows how it instills in young artists the value of vulnerability, storytelling and peer support. Nate’s a shining testament to that. The camp has been a great teacher to both of us, at different stages in our careers. Now he’s breaking out and using some of those principles to confront complex questions around prejudice, love, and power. That’s a tough blend to get right.

As well as creating an experimental writing app, Flowstate, you’ve also dabbled with virtual reality for your Eminem project, Marshall From Detroit – are you interested in using new tech to push the boundaries of filmmaking?

I think the heart of good art or fiction tends to be its earnestness; the ways it challenges sacred cows, pokes at our sense of purpose and investigates collective memory. It also helps to be funny. If fiction isn’t doing any of that on its own the tech won’t add much. Tarkovsky said art exists to remind us we’re going to die, and to prepare us for that death. That reads pretty heavy to most Americans, but there’s something to it. To me the difference between good fiction and content is that one is spiritually enriching and the other is there to wait out the clock. Good fiction doesn’t like wasting time. It doesn’t want you to hide. So tech can enhance art, but we shouldn’t confuse the two. Tech can’t create spiritual value.

That said, I’d love to make a video game. While it’s not a widely held position, I think there’s a case that Jonathan Blow’s The Witness is the best game ever made. It’s like he managed to interactively map the molecular structure of creativity itself, while zig-zagging between moments of magic and cold-plunges into existentialism. It’s not the sort of game I’d make, per se, but who wouldn’t want to explore a medium that can do that while still being fun as hell?

As a filmmaker, what other topics or themes are you passionate about?

Dialectic is a big passion of mine. The art of conversation. Everything from tenets of good journalism, to video game philosophy, to rock-climbing culture and Japanese history. Most topics I’m versed in have a link to some script I’m developing or plan to develop. The compulsion to spin yarns is a tough knob to dial down. And of course we can talk marketing and brand identity all day – I’ve put over a decade of thought into those for some pretty big companies – but the commercial vacuum can get a little stale without diverse sets of experiences to pull from. I think it’s important to develop a unique perspective on reality; an angle on who we are, where we are, and why we are.

And what’s in the pipeline, work wise, for 2021?

Last year I pitched a bizarre fantasy series, which ended up being the worst time in history to pitch a bizarre fantasy series. It was ambitious, out of control, provocative – right when the pandemic had networks scanning for safe bets. The script got great responses, but it’s on ice for now. Added to that, after years of research with my story partner Eric Martin we recently finished a mini-series pilot about Orson Welles’ doomed mission to Brazil, but haven’t taken it shopping for the above reasons.

So now I’m focusing on a story that doesn’t require a boatload of fiscal permission. In some ways it’s an extension of the visual approach and social awareness in enough., but fuelled by a mind-bending premise like nothing I’ve personally seen. You might say all those years of esoteric gaming are finally coming to bear. Anyway, I’m hunkered in Mexico City working on that script. The sun is crisp. The birds are carolling. It’s lovely, but there isn’t a day I don’t miss the storm like some far off, star-crossed lover.

Caleb Slain is repped by Superdoom.us