Joanna Nordahl

Tell me about your background, and your journey into filmmaking…

I grew up in a very small town in southern Sweden. I found my passion in theatre when I was young – I was taking acting, dance classes and hanging out at a local theatre. Later, at my high school, which was a very traditional, study-orientated school, I got involved in this musical theatre project run by students and I gradually got a bigger role as director of the project. It was only a tiny thing in a tiny town, but I do remember realising that I enjoyed directing: it was natural, instinctive. I didn’t know, at the time, that I would end up in film. But there was a sadness about directing stage productions: I was always upset when a production finished. That’s when I thought about film, because it lives on, and you can revisit that feeling forever.

In my early twenties I reached out to and did a few internships with directors and DPs that I admired, like feature director Tarik Saleh. Assisting on shoots, writing treatments, doing casting work, looking after the extras – I just wanted to soak up everything, while I experimented with making music videos on the side. I did a sneaky little move: I dropped out of film school in my last semester, but I could take the study loan to be able to afford travelling around to assist these directors.

I wasn’t a big film buff back then (more now), but I did have a huge interest in music, dance and theatre, and that sparked an interest in music videos. I was 100% an MTV kid, so [making music videos] was the coolest thing I could think of. The first video I made was for my own rock band, haha. At that time in Sweden, there were next to no female filmmakers around. I was in the industry for almost seven years before I met a female director. So I was making these videos, but I wasn’t sure I’d be able to make a living out of it, because I hadn’t seen any other women doing that. Getting into the commercial industry seemed to be a smart avenue for learning, hopefully making a living and growing as a director, as I couldn’t get in to (or pay for) the high end film schools. Now I find the commercial format a fun challenge, and there’s a lot of interesting projects going on.

BTS, Swedish Fairytale

What does your creative process look like? How do you capture your ideas, are you much of a planner?

I’m very sensitive to music: if a track speaks to me, or it emotionally sweeps me off my feet, it’s inevitable that I start projecting what it could be visually. It’s taken a long time to tame all my ideas and figure out which ones are worth doing – or doable, from a production standpoint.

I have a very hard time coming up with something from nothing. It needs to be a response, a reaction to something. When an idea comes to me, it’s a bit like Sudoku: I have to move things round until something clicks inside my brain. I don’t start writing immediately: I look at thousands of images, I listen to a lot of music. In a best case scenario, there’s time to let things breathe and marinade: I’ll write a first draft, let it rest, then have an epiphany in the shower and start writing again. But the reality of the commercial industry is that you have four days to do everything!

The process is much longer with my on-stage and dance projects: a year, two years of discussions and reading. It’s more like creating a long-format film.

Swedish Fairytale for Maria Nilsdotter

Alongside directing, you’ve kept in touch with your theatrical roots as one half of creative studio, Daae/Nordahl. How much crossover is there between heavily styled and staged films like Swedish Fairytale for Maria Nilsdotter and the performance art you create with choreographer Ludvig Daae?

I like to tap into that theatrical world when I can – it’s more forgiving, and free, and over-the-top. And researching a specific subject for a longer period can be extremely rewarding. A lot of my projects which aren’t [to a brief], have to do with inner life, escapism, emancipation and the future. I’m always trying to liberate my characters from something. I can definitely see red threads through my work in terms of the themes, but when it comes to the look, or vibe, it’s more instinctive.

For a long time, I felt like I had to almost apologise for doing these theatre projects on the side. People in the commercial industry can be very quick to put you in a box, but I feel like the world has moved past that: different [art forms] feed off each other.

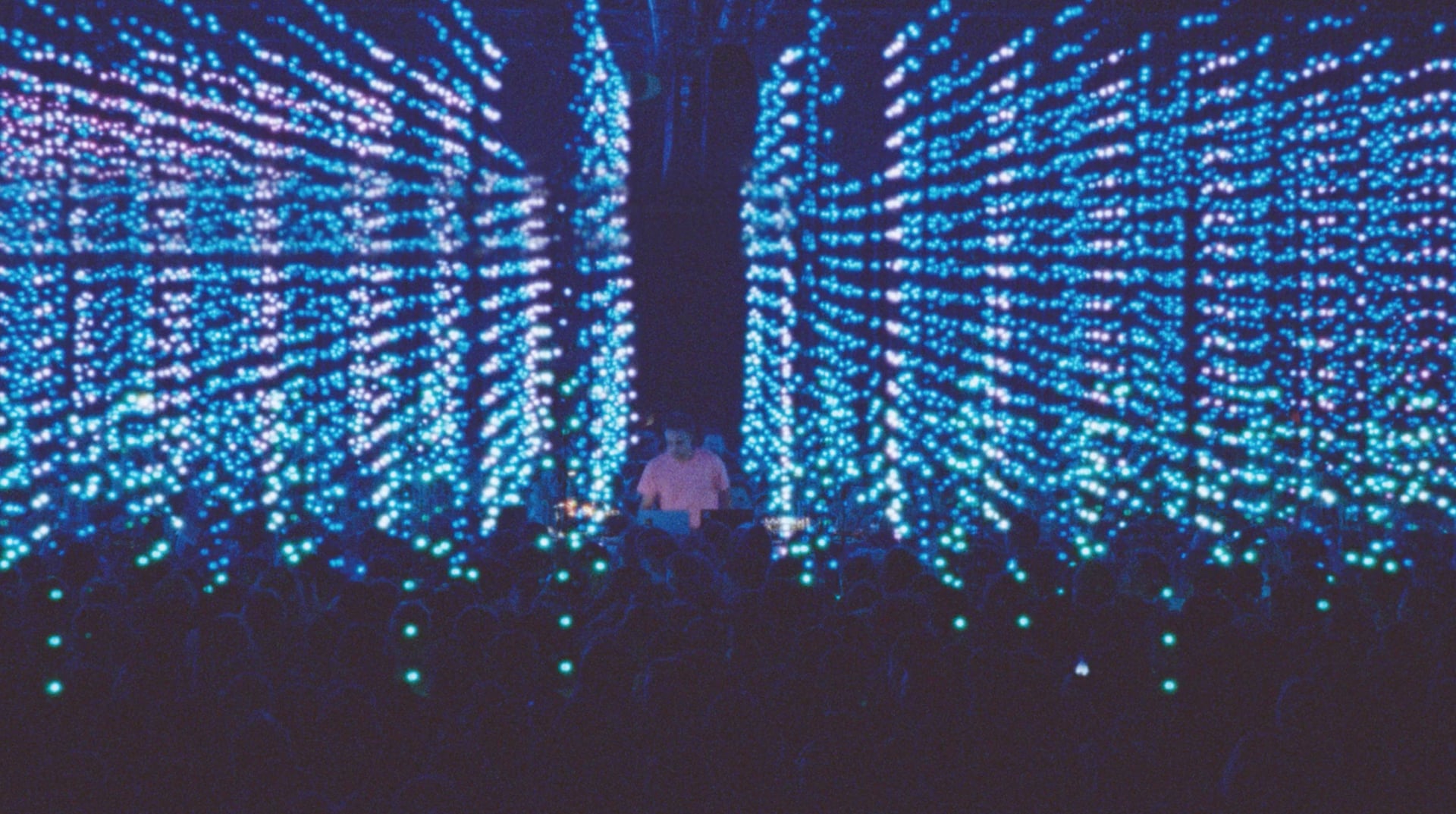

Drone scene for Four Tet, Baby

Let’s talk about your two films for Four Tet. Teenage Birdsong is interesting – the brief for the video was simply to document Four Tet’s comeback gigs at Alexandra Palace, but the end result is much more than that, capturing the emotion and intimacy in a way most concert videos don’t. What were the biggest creative and technical challenges involved in making the video?

Thank you, I am happy you enjoyed them. The way Kieran [Hebden] described the event to me, it sounded more like performance art. It was going to be his most ambitious gig ever, a homecoming, so he obviously wanted to record it, but didn’t know how. He didn’t want cameras on the floor, because he didn’t want to interfere with anyone’s experience of the concert.

My first thought was: it’s going to be like documenting a dance performance – [the viewer] won’t ‘feel’ anything. I knew this from my performance work: me and Ludvig have been researching the question of what it means to be ‘live’ in our collaborations over the past 10 years, and we’ve always had this dilemma, which is that our live show looks crap on film. You cannot document a live dance show well. It’s impossible to translate what’s happening in the room.

Initially we were thinking tech solutions, like 360-degree cameras, VR. Then I remembered that I’d met Josie and Connie [the two fans] at a shoot a year earlier. I got in touch with them, and pitched the concept, and they wanted to go to the concert anyway, so it all aligned.

The success of that video was because Kieran trusted my idea. I told him: ‘Josie and Connie are hilarious on camera, and super easy to direct; they are also brilliant visual artists, so they completely get it. Let’s still shoot it, and shoot it beautifully, on Super 16mm, paying respect to the concert, but if you just trust me to give it to them, it’s going to work. It needs to be about what it feels like, not what it looks like.’ And he was like: ‘yep, let’s do it.’ Which is obviously so rare in this industry.

Birds have landed, filming for Four Tet

You managed to bring the same emotional quality to the follow-up video for Baby, which interlinks drone footage of landscapes – both natural and manmade – around the globe, and could easily have felt a bit techy and abstract, like a Microsoft screensaver, instead of being this beautifully cinematic piece of work. How much of that came from the skill of the drone pilot and/or the decisions in the edit suite?

I was browsing Instagram and saw one of the clips that [drone pilot] Andrés Aguilera had shot – it had something like 100,000 views – and it blew my mind. It was drone shooting on a whole new level. Kieran sent me a few tracks, and Baby was the one that had the pulse of flying, plus there are already bird sounds in it.

I became obsessed with the idea that these two things [the drone shooting and the track] should be put together: they couldn’t exist separately any more, so we started a remote conversation with Andrés. There was a lot of back and forth: it took a while for him to ‘see’ what I was looking for: at the beginning, he was sending me the most impressive footage, like flying under a bridge, or really close to a moving car, when I wanted the most emotional stuff. But he really understood it when he heard the track and we started adding the visual effects. It was a really fun collaboration, he’s incredible.

I’d always wanted to bring back the two fans [from Teenage Birdsong]. The original ending in that video was that they’d fly away, but it ended up being impossible for many reasons, so we just ended with them growing wings. For Baby, we were considering putting a rig on them and filming them flying in mid-air, but there were the same dilemmas as the first video. Then it came to me when I was walking to the pub in London, chuckling to myself: have them do a really crap landing!

Your lockdown short, Admiring u, is a montage of footage shot between 2013-2019, which feels incredibly personal and poignant, in particular the scenes from festivals, which feel like a snapshot from another era completely. Tell us about the process of creating the film over lockdown last year.

That was part of an online initiative called Shelter Shorts, which was started by a couple of filmmakers in New York to get other filmmakers to create things [over lockdown] rather than getting depressed. Crystal Moselle nominated me. I was already feeling very fragile as a freelancer and not having work, so it was a terrifying time. [Admiring u] was something I started making to calm myself down.

I’m a very nostalgic person: reliving past memories through photos makes me sad – but ‘happy-sad’. So I went through my old hard drive and found every photo I’d taken since 2013, and started looking for moments that had that feeling of spontaneous togetherness, what it means to be human at its finest. Love being exchanged between people in random ways. Ecstasy in music and dancing. People being drunk. Primal moments that touched me.

That’s what I want to do as a filmmaker: create moving experiences. I have a little motto: what moves you, makes you move. The film was very much a reflection of that.

You’ve just got back from South Africa, where you were shooting a new commercial for WhatsApp, and got trapped there over Christmas. That must have been tough…

When the script landed in my lap, it was very hypothetical. There were beautiful characters in there, but it was very open. That was actually blessing for me, because we only had a month to make the whole film. I’ve never done a production that fast in my life. The curse of that timeline is, of course, that it’s going to be tough. But the blessing is that very quickly, you’re going to have to trust each other completely.

The agency’s dilemma was that they wanted to show the family group chat, but they were worried about all the text and having to translate it to four different languages. I got two days to think about it and woke up in the middle of the night with this idea of using voiceovers and music as the motor and instead of scrolling through a phone, literally scrolling through live action scenes.

The client bought into the concept super quick, which was a blessing, and then we had nine days to prep the shoot. But I was in the lucky position where I could pick my team, so I trust the process – even though the timing was tight, if you know you’ve got brilliant producers, a brilliant DOP, sound designer, editor that you trust then you’re going to end up with something that is not nothing. It was released the day we finished it.

And yes, all our flights home were cancelled, but I feel like it summarised this year and we all kind of channeled it into the film.

As a director who loves travelling round the world, this year of restrictions and closed borders must have been tough creatively. Were there any silver linings for you?

With the WhatsApp project in particular, I felt extremely blessed to be in the sun. I’m in Stockholm now, and we have about one hour of daylight per day. Right up to the point that job landed, I was feeling like I had to escape [from Stockholm] and go surfing or something to not go crazy. I’m 50% Brazilian, so this isn’t my natural habitat in the winter haha.

I’m starting another project now, that I’m super excited about, but it’s still messy and complicated with Covid. Where are we going to shoot it? How are we going to shoot it? Can we shoot it? But at the end of the day, I have a job. The first six months of the pandemic were so scary, because I didn’t, so I count my blessings every day.

What are you working on at the moment?

I’m doing a brand project right now about the future of fashion. I’m almost scared to say it, but I am also writing: I’m trying to put more long-form stuff on paper. I feel emotionally ready for it, but taking the time off to write is difficult, because it means saying no to collaborations that excite me.

Interview by Selena Schleh

New Land website