Camille Summers-Valli

You were born in Bangkok, raised in Nepal and currently live between London and Berlin – how has your peripatetic life, and experience of different cultures, influenced your work?

Growing up in a developing country (Nepal) allowed me to be acutely aware of our privilege in the west, and the fortune I have to be doing something I love for work (more so, having access to healthcare and food). Simultaneously, growing up in Nepal allowed me to have a profound understanding and respect for land-based cultures and communities, something that always, somehow, comes back to the core of what I do.

As an adult, I understand that different geographic spaces allow for different experiences and, therefore, ideas. I love the pressure of working in a city like London or Paris, where I survive off the fast pulse of the cities. In Berlin, I stop and read and take care of myself, sit on projects that need time and space and reflection.

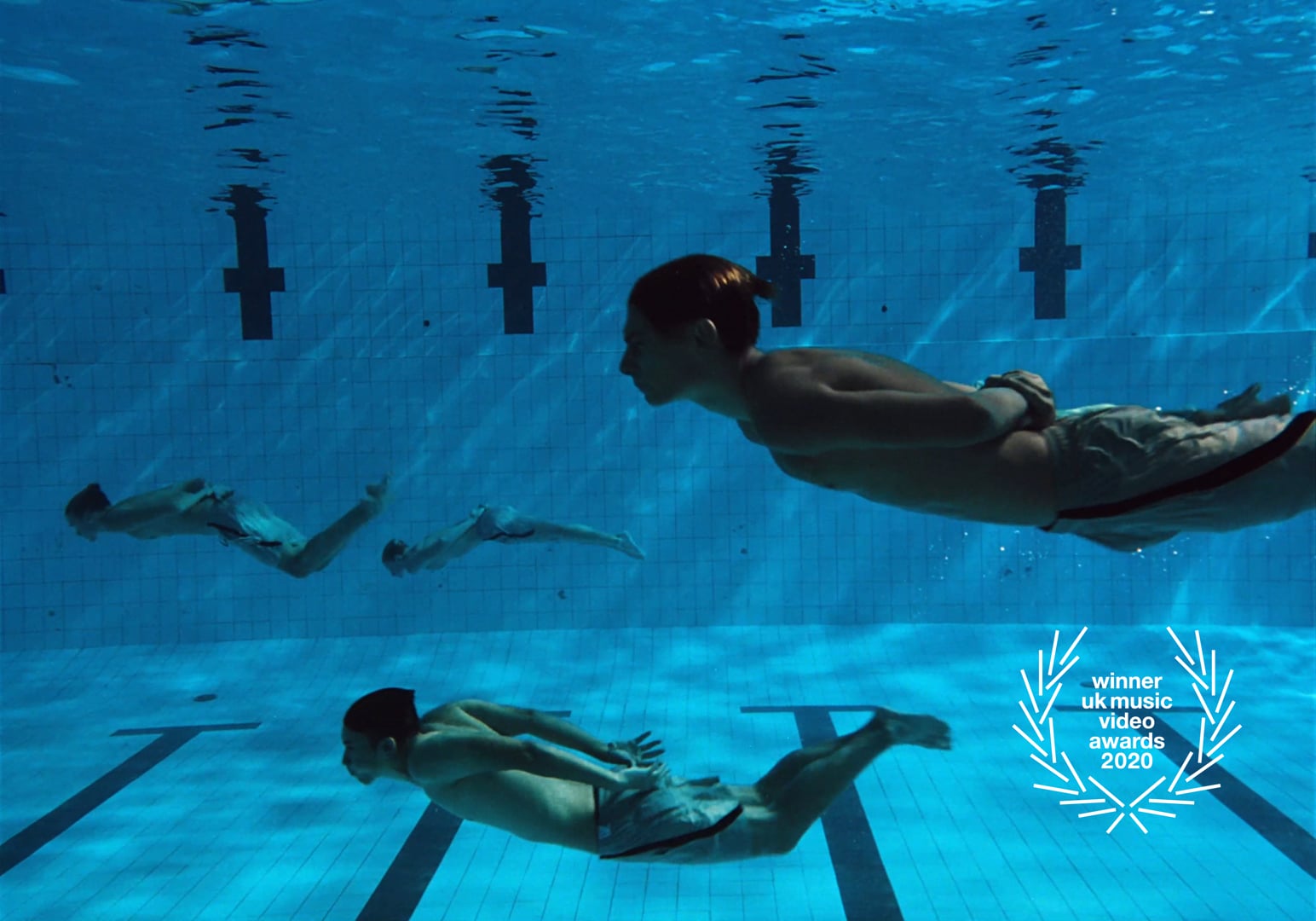

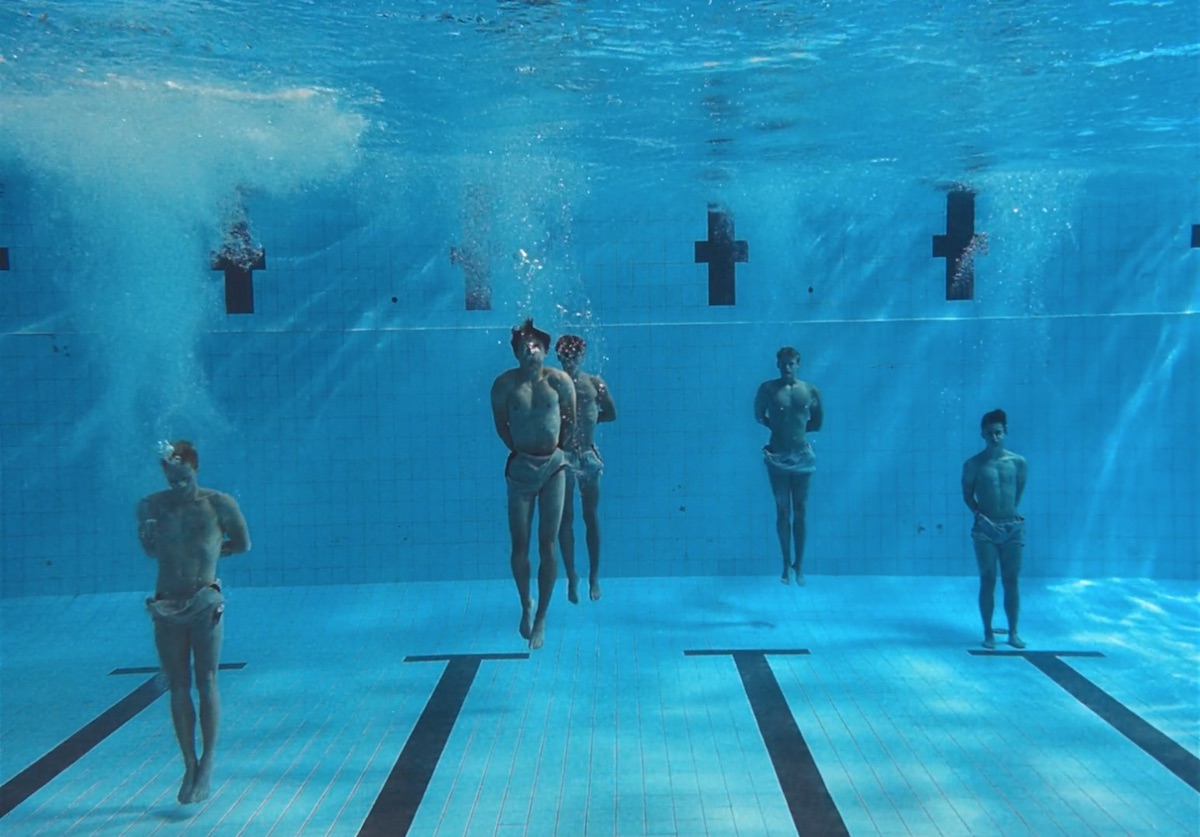

Swim Hunt Run, Alaska

How much was your career in photography and filmmaking inspired by your father, a documentary-maker?

Isn’t it the case that children don’t want to be like their parents until they wake up one morning, and, lo and behold, they are? In my case, that’s true…ish. I’m not entirely like him. My mother is pragmatic and level-headed. I believe I may have inherited some traits from my father and a lot from my mother.

My father told me that I should ‘follow my dreams’, by any means necessary; he did just that in his own life. I watched him make a living and a career out of his passions, therefore I guess I was less afraid to take this path.

As far as direct inspiration? Not so much. I constantly challenge and question the role of the photographer and filmmaker in a documentary space, so it’s conflicted. My questions and concerns around his practice have shaped mine.

Camille Summers-Valli photography

Much of your work feels like stepping into a dream – it has that fluidity, that ability to defy gravity or reverse time, and is full of images which appear unconnected but are somehow linked together. What does the creative process look like for you?

It is very image-led. Images from books and from life burn into my mind. I string them together in a way that is not at all theoretical but, purely instinctive. Once they’re all together, I’m like: ‘Oh yes, of course that film is about humankind’s fragmented relationship with the natural world!’ Or whatever else the film might be about.

I love this way of working, but now I really enjoy collaborating with writers. I’m so excited by the idea of making images work with language and narrative in a way that it accentuates it, develops it, allows it to be something else.

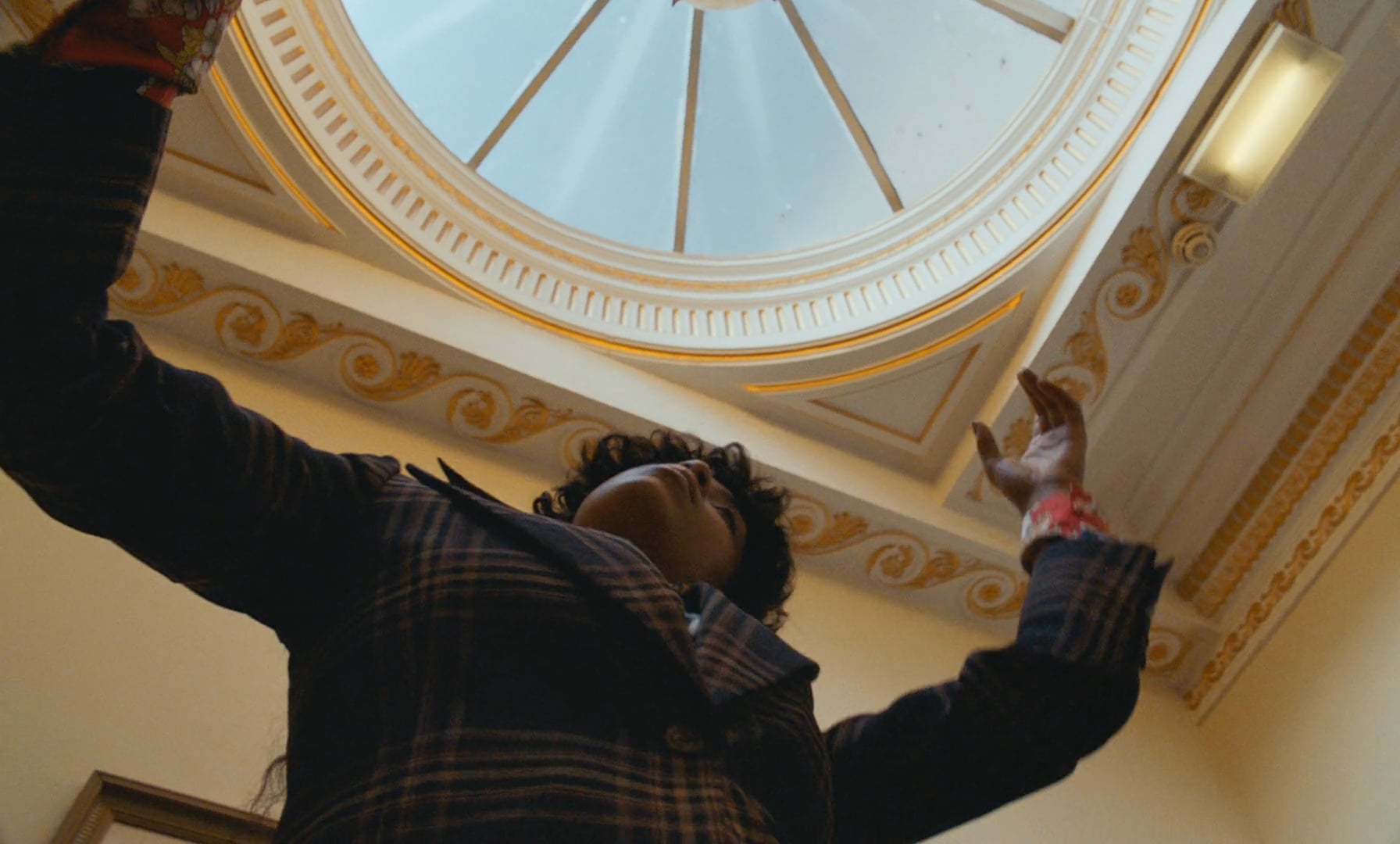

Lapsley My Love Was Like the Rain

Your photographer’s eye is evident in the striking staged imagery of films like Kenzie’s Dark July/ Funeral, and Lapsley’s For My Love Was Like The Rain. Do you share a visual language with your long-term DOP, Maximillian Pivner? How do the two of you work together?

We work very closely, not only on individual projects but we are constantly sharing images and ideas with each other. We have very similar taste and aspirations when it comes to a visual identity, but it’s taken time to build. He’s a complete perfectionist; I am not. This is a crucial piece of the puzzle as he pushes me to be more precise.

Lapsley My Love Was Like the Rain

Who or what are your biggest creative influences?

Nature is a big one. It’s in the top three.

Also, places that live between being modernised but still have a foot in a land-based way of living. Places like these shed light on some of the failures of modern culture and remind me how cool it is to live closely to the natural world. I find some modern ways of living hilarious, when they are starkly contrasted by the immensity of nature. Dry humour is a creative influence.

Then, artists such as Taryn Simon, Kara Walker, ChrisBan Marclay, Chris Marker. Jean Paul Goude. David La Chapelle. John Divola. Chantal Akerman. I could go on. Douglas Coupland. Lynne Ramsey. Issey Miyake. Guy Bourdain. Ansel Adams. Ben Rivers. I’ll stop, but the list goes on.

IFAD, Still I Rise

While making your first feature-length documentary, Big Mountain, you spent three years herding sheep and getting to know your subjects before even picking up a camera, which seems like incredible dedication to the cause. Are you someone who lives and breathes each project, or was this something specific to that particular film?

I was herding sheep before I became a filmmaker. I never went to the area, Big Mountain, on Navajo Nation, Arizona with the intention of making a film ([I was] trying hard not to be like my father at this point). I went as a sheepherder, working in solidarity with Native American elders who are still trying to defend their homelands against resource extraction. Two years in, Danny Blackgoat, an elder of the community turned to me and asked me if I wanted to make a film. I couldn’t say no. I was at art school at the time and I had access to a Canon 6D and shot the film. He made me a filmmaker.

As for now, it would be romantic to say that I live and breathe each project. Balancing commercials with personal work with photography, I live projects without necessarily breathing them also. Call it a work-life balance.

Camille Summers-Valli photography

Your new video art installation, Swim Hunt Run, interrogates the broken connection between humans and nature, and our doomed attempts to rebuild it. What inspired the idea for the film, and can you tell us a bit about how you brought the concept to life and how it will work as an immersive installation?

The broken connection between humans and nature is one of my biggest creative influences, really. I guess it goes back to my childhood in Nepal where I witnessed the rapid westernisation of remote areas. It acutely highlighted the difficulty we have as humans in accepting the natural world as something we are part of. This idea is a critical part of my personal practice.

I had been to Alaska before, and it was one of those places that had really burnt itself into my imagination. Max Pivner, my DOP, told me to stop searching for flights to Alaska and to actually book one. So we went there last summer without much of a plan; we had a shot list, we had a bunch of 35mm film stock left over from a commercial, we had a camera… and off we went.

As far as the exhibition, I come from a background in video art so I really like to consider the way something is seen. The work has already been exhibited in a beautiful space in Lisbon, on two 6m screens which you can get rather lost in. Niel Johnson did an amazing job on the sound, so the room trembles as a polar bear plunges into the water. It’s an attempt to be visceral with film. Hopefully, London will be next for a screening.

Gucci + Dazed Beauty, Growing Pains

What else are you working on at the moment?

Project number one: how to do lockdown in winter in Berlin while staying sane.

Number two: a short film, or video art piece (I don’t know how to label my films) written with Edie Campbell.

Number three: a book of postcards that Max and I took during the process of making Swim Hunt Run.

Interview by Selena Schleh

Camille Summers-Valli website

Somesuch website