Zebra Katz

What was your childhood like – was it a particularly creative background?

I grew up in the far away countryside of Sweden, in a big house surrounded by deep forest and a view that stretched across vast meadows. The whole place was suffused with the magical atmosphere found in fairy tales, certain poems or of that in the first episode – Sunshine Through The Rain – from Kurosawa’s film Yume (Dreams, 1990) – a film that has made a huge impact on me.

The bookshelves in my and my siblings’ rooms were filled to the brim with children’s books. Storytelling, music, film and building secret forest huts, characterised my childhood. My hard-working parents weren’t active in the creative field in particular but created a creative and allowing place for me to grow up in. I discovered the power of moving images at an early age and started to make my own films as an 11 year-old. Films that were made on a simple camcorder which a friend and I got our hands on by picking the lock on his dad’s bar cabinet when he wasn’t around.

I wanted to make real films. But there was no one around to teach me. This was right before the Internet turned into the vast source of knowledge it is today. I didn’t even know what a script was. All I knew was that I loved the feeling of capturing my world with a camera, turning my imagination into reality, capturing details, the shifting of the light, playing with music through images. The camera became like a beloved instrument to me and even though I’ve been to schools studying the fields involved in filmmaking I would say I’m mainly autodidact in what I do.

Ever since I first found my interest, my passion has been to explore the powerful relationship between dynamic images, sound and music. Regardless of whether I’m working with a film script, an art project, a music piece or a poem, I’m driven by a desire to portray emotions, state of mind and atmospheres.

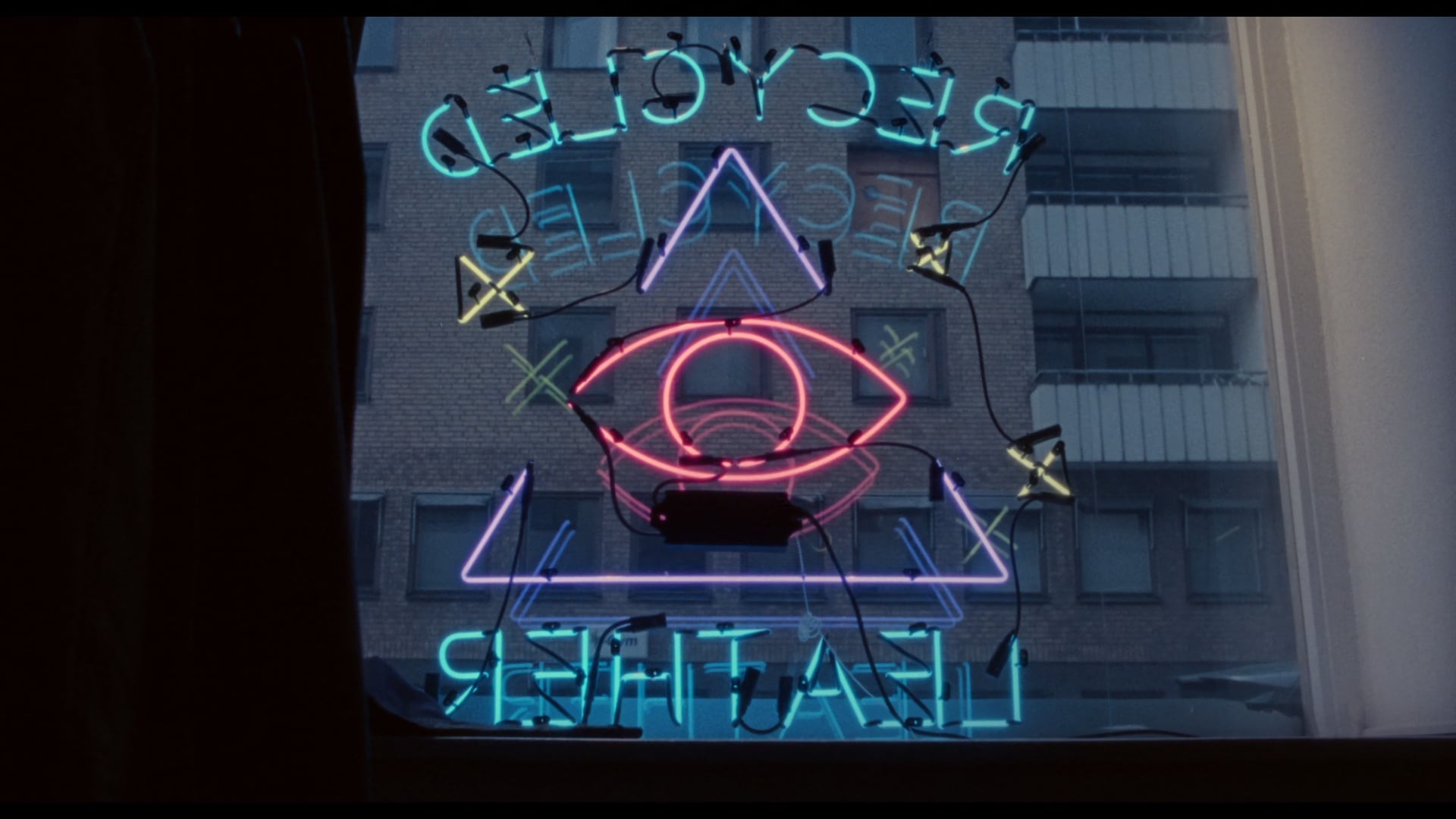

Zebra Katz, Lousy / In In In

It’s difficult to sum up your directing aesthetic – your sensuous music video for Zebra Katz couldn’t be more disparate from an earlier film with the Swedish musician Jenny Wilson, Beyond That Wasteland. The former zooms in on textures and deep warm tones whereas the latter focuses on vast bleak cold landscapes perhaps echoing the singer’s internal struggle at the time. Is it your relationship to the lyrics that guides your aesthetic or is it born out of close collaboration with the artists?

If we’re talking collaborations with music artists lyrics are definitely important and a key to inspiration and ideas, but my ambition is to avoid interpreting them too closely and rather use them as suggestions for a foundation of theme and attitude. More important is my close collaboration with the artists, sharing flow folders with a stream of refs, aligning on some kind of treatment and concept, cast, locations, styling etc. Keeping the communication open and alive. Sometimes what the artists think they need can differ from what I think they need. I’ve learned to insist on that through the years, whilst listening carefully.

And important to say, it hasn’t always been successful. Sometimes we didn’t align well enough beforehand and the artists or label rejected the final thing. With any kind of commissioned work, I think it’s essential to have the artist, label or client be present on the set in most cases. It will create a loyalty to the material and a will to see it released. The projects I did that were rejected have one thing in common and that is that the artist, label and/or client were not with us during the shoot.

As for directing aesthetics, I don’t want to repeat myself too much in what I do. Some aesthetics, some touch, will of course always be there as my signature even if the films take different forms and employ different lensing etc.

Jenny Wilson, Beyond the Wasteland

You not only write and direct your own films and music videos but you also edit and quite often shoot them. How important is it for you to craft your own storytelling?

Every project calls for a different brush. Some are more sensitive and naked and require a minimum of human filters involved between the idea and the execution of it. Or they are gritty, fast and lo-fi and something can be gained from me shooting it for that reason. It totally depends on the project and the scale of it. I wouldn’t take on the role of the DoP if the size of the crew was normal or large and if there was an agency/label/client involved and there was a real budget. The bigger the production the more every function needs to focus solely on their one role, and for me that is being a director.

The editing part comes from my background of editing all my stuff myself in the beginning. I still often do my own director’s cuts, but my preference is to always work with carefully selected DoPs, editors etc. and if the selection is right the outcome will always benefit tremendously from my collaborator’s talent and sensibility. But some projects just force me to get hands-on, no matter if I want to or not, it’s just the nature of the material and how it passes through me.

I just try to follow my intuition and I like to challenge myself. I’ve also produced more or less all my films and music videos myself, out of necessity, but I’d prefer to work with a producer any day of the week.

The Acid

You sometimes evolve pieces of your work into other mediums – for instance, the art exhibition, ºıı˙∞˚ ‡ ^ ˚ ‘ ^^ ˚, based on your film for The Acid that explores “the idea of a place and a state beyond the networked society and its excess consumption of information. A spiritual retreat where you go to be cleansed, where the digital pollution we all carry – one’s digital spirit – can be expelled. It’s an equally painful, uncertain and euphoric state, with no possibility of turning back.” How does your experience as a director influence your art installations (or vice versa)?

Perhaps in how I try to build some narrative and pacing for the viewer and in how I work with an audiovisual experience, lighting it, creating a soundtrack etc. In ºıı˙∞˚ ‡^˚ ’^^˚ characters from the film were part of the exhibition, in costume, guiding the visitors into this universe and finally presented the premiere projection of the film by performing a ritual similar to the one in the film. So there was an element of meta to it and blurry lines between film and art project.

From the exhibition N.N.

Do your personal projects inform your commercial work or is it a completely different creative process and you usually stick to a tight brief? Do you like to nail everything down in minute detail in pre-production?

I’m most happy when I can bring my personal signature and ideas to a commercial project, but I have done things that were strictly on brief as well. I see it as part of the job when directing for a client that you need to be able to step in and out of your personal artistry and sometimes just deliver high quality craft, objectively speaking. It’s a choice that has to be made when choosing a project, I just need to have a dialogue with myself and come to clarity on why and what I want to get out of it. Today, I’m mainly doing commercial work where my personal influence is requested.

I usually like when there is room for intuition and exploration but I also have a perfectionist tendency, so I’m an advocate of nailing many things and leaving as few questions as possible unanswered in pre-prod, but with the purpose of starting the shoot on the safe side, not wasting precious time on the wrong things and allowing us more room to play and reach for more.

Acid, ºıı˙∞˚ ‡ ^ ˚ ‘ ^^ ˚

Your short films usually take us to some unpredictable place often with a tension that we’re expecting something ghastly to happen without emotionally alienating us from the characters. What inspired you to write Kleptomania?

When I was in film school (Czech National Film Academy FAMU in Prague) we got to do this exercise called The Meeting. The idea was to show a meeting between two persons without using dialogue, only relying on visual storytelling. Some years later I decided to do the exercise again for myself but tweaking it a bit, extending it into a short film and adding the parameter of letting the characters be of very different age and background, two persons that would normally never have met.

Let’s talk about your latest film for the two tracks, Lousy and In In In, from Zebra Katz’s album Less is Moor. The framing, the lighting and detailed art direction create a seamless flow of visual richness. Please tell us more about the ideas behind your narrative and what you wanted to portray? Did the fusion of imagery and the beat come together in the edit or did you have it mapped out before the shoot?

I see the film as a depiction and exploration of soft and hard masculinity, between introvert and extrovert. The brief was to visually and sonically reintroduce Zebra Katz before his debut studio album release, and I knew I wanted to create something different than an ordinary music video. My idea was to go for a setting and theme of self-care, using hypnotically introvert mundane everyday actions such as ironing and rehydrating in LOUSY to gradually peeking into something much higher, more extrovert and forceful – even otherworldly – with the upbeat forwardness of IN IN IN. The two tracks are never played out in their entirety but are edited into chapters that we go in and out of through the film – portraying a dynamic duality that I see between two sides of Zebra Katz’ persona.

I did a breakdown of the chapters beforehand and listed the visuals I wanted to correspond to each chapter, so yes it was pretty much mapped out, but there was also room in the schedule for several unplanned shots and some of the shots belonging to one chapter were intuitively used in a different spot in the final edit.

From Lousy / In In In

Zebra Katz’s film looks effortless, was it?

Overall it was a quite smooth shoot, but there was some logistical hassle gathering everyone and the equipment from several different countries and cities to come in time to the Swedish west coast. For example, the day before the shoot we didn’t have the 2-perf 35mm camera as it was late from another shoot, but sometimes you just need to have zen and believe. It was also a Fitzcarraldo-like experience getting the whole crew and gear in and out of the location of the wooden fortress (Nimis by artist Lars Vilks), an extremely remote and inaccessible place deep into a nature reserve that can only be reached through climbing steep cliffs and where it’s very easy to get lost when you’re shooting in dusk and need to get all the way back up in the dark.

From The Acid ºıı˙∞˚ ‡ ^ ˚ ‘ ^^ ˚

And finally how do you tap into your own creativeness? Anything in particular that triggers inspiration?

Physical activities, using my body and recreation like swimming, jogging, walking, gymming, showering and lots and lots of music. Basically anything that involves using the left side of the brain, so that the right side can cook up creative ideas by itself in the background.

Daniel Wirtberg

Daniel Wirtberg website