The Horrors’ Ghost

You’ve known each other since film school. How did you begin working as a duo and what does that look like these days, practically, on a job?

We bonded during the unsurprisingly undersubscribed experimental film module at university. It was here that we developed an interest in the more leftfield, playful aspects of film history. Stuff that celebrates film for what it is and isn’t necessarily anchored to a script. This felt like the right meeting point for us, in respect of our personal tastes and also in relation to the music video as a visual form.

Whilst we didn’t actively collaborate at university, there was a sort of silent appreciation of one another from afar. Once we left university, we finally broke the ice with a bunch of low-budget music videos for mates’ bands and gradually one project led to another until we caught the interest of Natalie Arnett. And that’s pretty much how we find ourselves at Riff Raff now. Those early videos were pretty formative for us in terms of honing a style and a workflow.

Role-wise, nothing is set in stone, and so far we’ve tried to split everything 50/50. If one naturally takes the lead in one respect, the other will pick up the reins in another. Production poses both creative and logistical problems so there’s always plenty to do. There are of course creative differences along the way but we’ve always stuck by the good old motto: thesis-antithesis-synthesis.

Much of your work explores the uncanny space where something familiar and recognisable – such as the human body – becomes unknown, alien, even otherworldly. What interests you about this space?

There’s a curiosity, especially when making music videos, to try to bring something new to the table. We’re both interested in the experimental tradition, and art more broadly, and we often take our cue from there.

I guess that liminality you mention (a word we use too often in treatments) is a result of this. Certain tracks/briefs suit these kinds of images more than others so we are definitely mindful of that in the pitching process. We want to make these videos as engaging for the audience as possible, but not be so abstract that the piece becomes unintelligible. There is always a balance to be struck. Hopefully in/out inhabits a space where the ideas are fresh and accessible and most importantly in sync with the tempo and feel of the music.

What’s exciting about the music video for us is the opportunity to try new things out. It seems like the perfect form to create a visual language outside of narrative (successfully or not). Don’t get us wrong, we love drama and narrative but we tend to see that as a separate endeavour to music videos. That is certainly not to say that people aren’t making great work in that vein.

For us, it shouldn’t feel like a short film or a visualiser. It sits somewhere in between, hopefully becoming its own thing: a music video.

Moses Boyd’s Stranger the Fiction

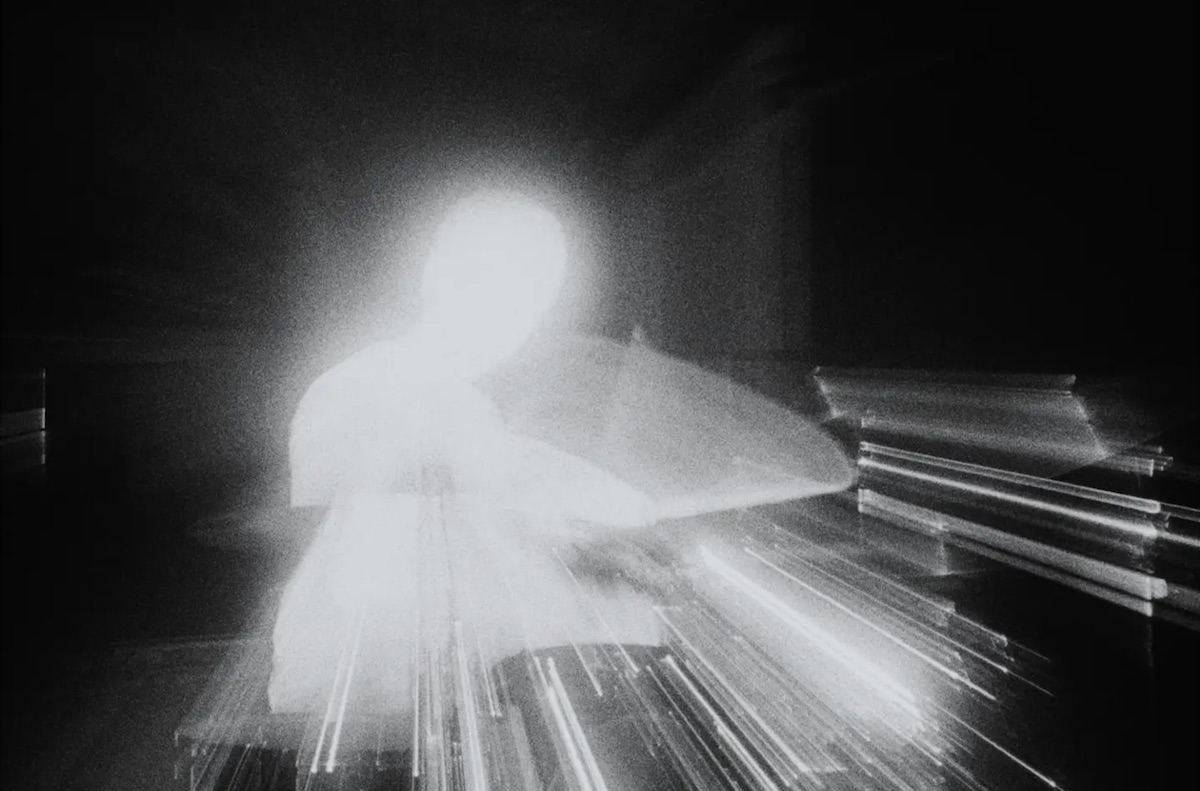

Your latest video, for Moses Boyd’s Stranger Than Fiction, is full of mesmerising effects, such as the white-hot glow surrounding the performers. What was the brief and can you tell us a bit more about the shoot and how you achieved the unique look and feel?

In practical terms, the effect was achieved using a reflective spray and a singular spotlight, totally aligned with the lens of the camera. If not, the spray was imperceptible. We shot tests on our iPhones which were deceptively good as the lens and flash light are pretty much bang in line. There were difficulties however when this had to be upscaled to a film camera and more powerful light. Thankfully, our DP Spike Morris was on top of all this.

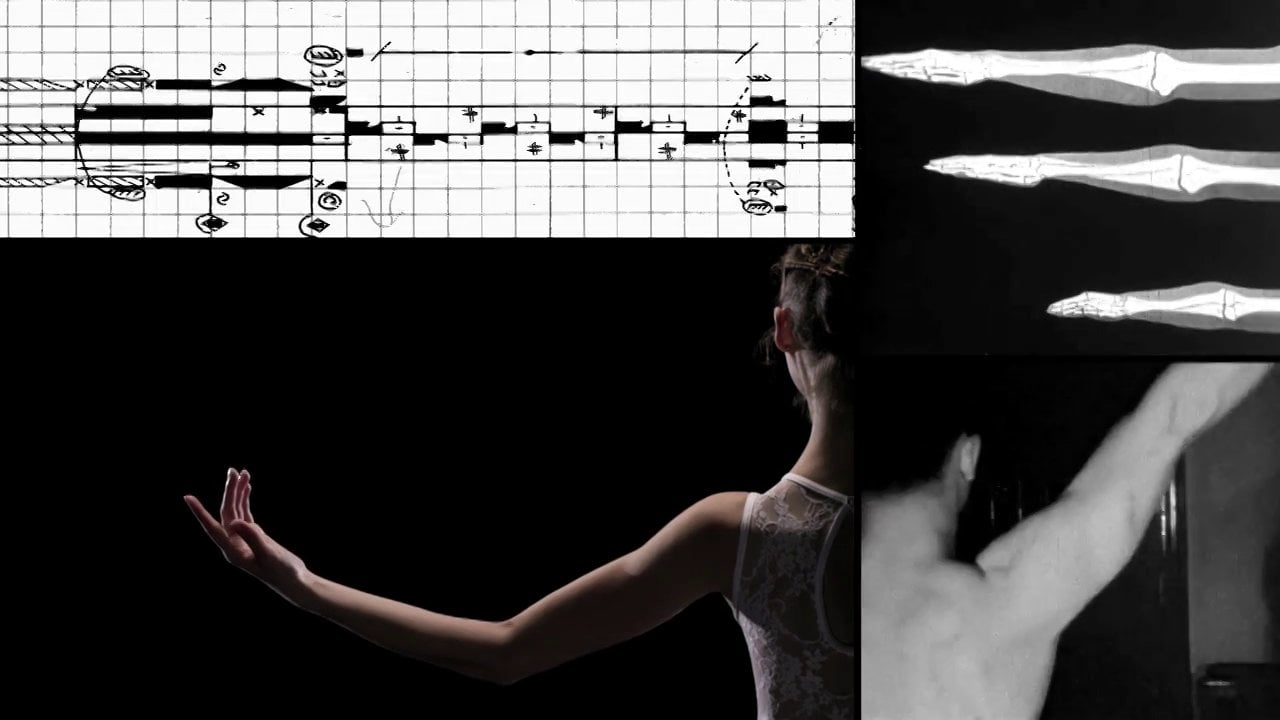

Outside of the look and feel of the film, the word from the brief that stuck out to us was this sense of ‘hyper-musicality’. It’s an abstract concept, especially in relation to imagery, but that is precisely what excited us. In this respect, our response was a kind of ‘hyper-visuality’ – coming up with a bunch of setups that could only be experienced visually, in total lockstep with the music.

We wanted to use the materiality of film as an instrument by manipulating shutter speeds, frame rates and exposures. This all helped in building rhythm and punctuation when it came to the edit.

When watching cinema (or any visual medium), you’re usually drawn to a face, or somebody’s eyes. This anonymising haloing effect hopefully brings you closer to the musicality, the performances and the visual experience as a whole.

Stranger Than Fiction, like Ghost, demonstrates your delight in pushing the boundaries for in-camera work, be it through thermal imaging or photographic exposure. How do you approach the technical side of things – do you plot everything meticulously in pre-production or is more of an organic process on the day?

The pre-production reflects the nature of the project at hand. This video happened to be a fairly technical one, from the reflective spray to the looping trajectories. We like to think we’re fairly methodical in pre-production – driven from a sense of fear mainly. The more we test and plan, the more we hope we’re limiting mishaps on the day. But that is hardly ever the case.

Film sets (especially music videos) are very time sensitive arenas so you rarely have time to experiment and tinker. That’s not to say new decisions and turns are not taken on set. You still have to be adaptive and be able to compromise. In general, every shoot feels a little like a failure in comparison to what was in mind, but that might be just us.

The edit is then much more organic with lots of trial and error, but we’re afforded way more time here. And there’s an undo button.

Plaitum’s Jagwa

Music videos can sometimes suffer from a disconnect between the track and the visuals – as if the director was intent on making a certain sort of film and then found a track to plonk on top – but in your work, the synergy between the two is striking, such as the abusive relationship depicted in Plaitum’s Jagwa. When it comes to representing a song visually, what’s the starting point for your creative process and to what extent are you guided by the lyrics?

We both have pretty different tastes in normal life, but we respond visually to the same sort of stuff. Conveniently.

We tend to work off visual references, be they provided or found. We also talk about broader themes and conceptual underpinnings, but loosely. It’s mostly about cracking that initial visual and getting the right vibe for the song. That one hook can then lead us down a rabbit hole of research.

Lots of new ideas and accents to the treatment come further down the line. It’s rarely ‘oven ready’ from the offset. We can sometimes suffer a bit from ‘everything-itis’ so a natural culling process is important too. That can happen in the edit as much as pre-production or even on the shoot day.

Throughout this process it’s always important to listen to the music at certain milestones, but not to be obsessive about the track (that comes in the edit for us). You have to find your own voice in the mix.

What’s the appeal of “doing things for real” rather than relying on post? And what’s the most challenging job, technically, that you’ve ever done?

There is a sort of natural resonance with doing things ‘in the real.’ Appreciate that sounds a little bit hifalutin, but it’s something about being true to the ghosts of films – the history – the range and scope of the medium. The result always seems to pay off and you’re rewarded for the extra effort.

Maybe there’s less of a throughline nowadays and more of a shortcut between the initial imaginative spark and post production. And this sometimes overlooks the inherent qualities of the medium and the sculpting that you can achieve in situ. Horses for courses though. It’s not a catch all philosophy for sure and we wouldn’t say we’re absolutists either way. It’s more about ‘doing things that feel right’.

Each project feels like a different technical challenge. Often the most simple challenges can turn out to be anything but. We have a knack of making things difficult for ourselves too, but again, it’s all in the service of bottling up that desired ‘feeling.’

The Guinness spot was the most intimidating, launching 15 or so people into the air on wires simultaneously certainly had our hearts in our mouths. The music video ‘Red’ for Mt. Wolf was the most technically peculiar piece we’ve done. Eroding and scratching celluloid with bleach, nail scissors and acetates. Pretty smelly one, that.

Guinness, Liquid Tumble

You’ve also dipped a toe in the commercials world with a spot for Guinness – are you hoping to do more or stick with music videos for now?

A singular toe, yes. That was an unexpectedly big step up for us and kind of happened out of the blue but came as a direct result of a music video we had made. The creatives wanted to work with newer talent and had the confidence to back us, and hopefully that paid off.

It was a real eye-opener. In a way, it’s a little like the inverse of music videos. In the sense that time, budgets, equipment and personnel afford you endless possibilities. The question then is: where does that stop? Often in music videos you’re working with a variety of restrictions which can help make decisions for you. All in all though, we ended up enjoying the whole experience.

A big thank you to Matt Fone at Riff Raff and the creatives Nick and Nadja at AMV for entrusting us with that one.

So yeah, more please, of everything.

What other projects do you have in the pipeline, now that lockdown is lifting in the UK?

Nothing confirmed right now. A music video treatment in the works and then individual editing work and personal writing outside of that.

Interview by Selena Schleh

in/out is represented by Riff Raff