What made you move to LA from London and what impact did that have on you?

I went to California on a roadtrip in 2009 and just loved the pace and weather and having grown up in the 90s I was transfixed by the iconography of LA in the films I’d watched – I was under its spell. LA really is the global hub for film and TV and I just knew I had to be there for a while and experience it for myself.

Both sides of my family are from different parts of the world and they moved to England for more opportunity. So from a young age I had that example right in front of me. Also one of my best friends, the artist Pauli The PSM, had moved to New York a few years before and I saw how he’d grown both professionally and as a person, so for these reasons I wanted to move out of my comfort zone and explore that.

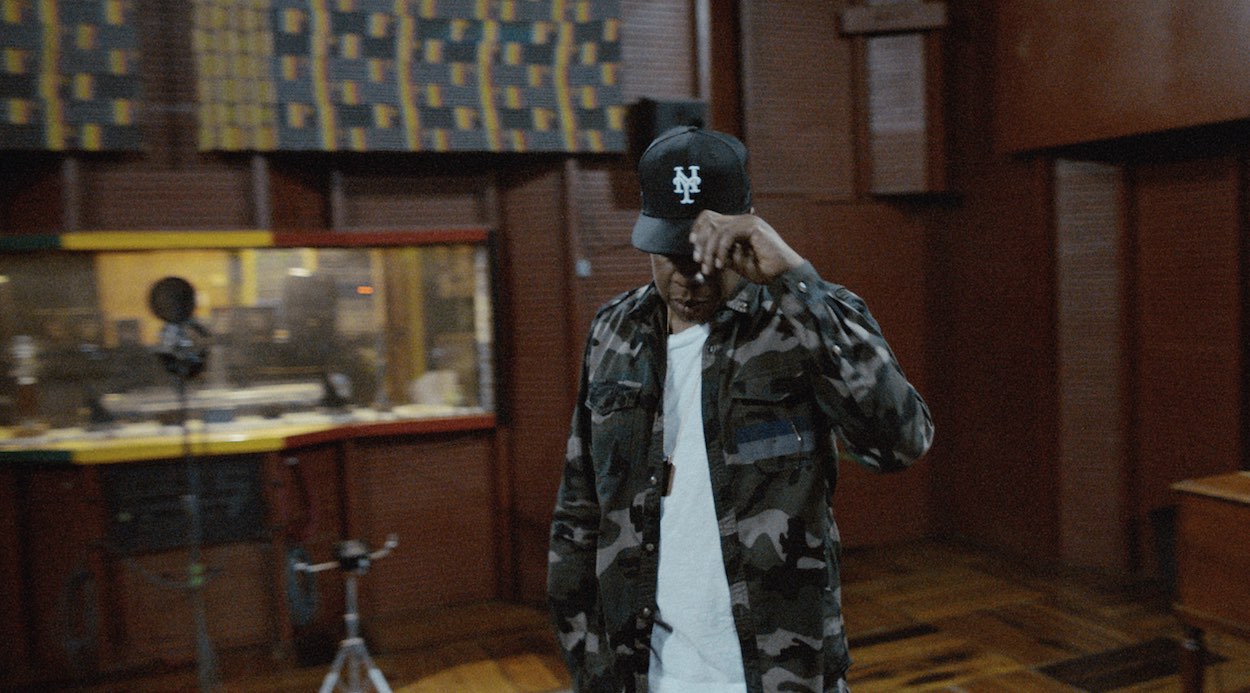

From Jay Z’s Bam

Elaborating on that, what was behind your decision to experiment with traditional formats, combining music video and documentary film for instance in your films Bam, When I See You I See Me, Nasir, Rest In Power…?

When I started, I had no budget to control anything – just my Canon DSLR camera and my eye. So my early work, documentary by nature, formed my reel in a professional sense. I always wanted to develop my own style and play with conventions in short form. I also wanted my work to feel emotive, cinematic and thought provoking, so I focused on really looking at the subjects in my films – who they are as people, what drives them, how they feel, the journey they are on.

Bam for example is the best version of my documentary style I’ve made so far and the closest to what I envision. That project tells the story of legacy and the importance of Jamaica’s rich culture to the world. When I first heard the song I was drawn to the sample of the iconic Sister Nancy track. She told me [Bam Bam] was something she freestyled on the spot and it’s crazy that it became this unifying cultural force – Jay-Z, Damian Marley and myself all grew up listening to and it brought us all together for this project.

Ultimately I love these projects and they turned out exactly the way I wanted them to. I’m really proud of all the films you mentioned, they speak on issues and themes that I truly believe in so I had to make them.

From Nasir

Your work is compelling. There is intent and there is grace. How much carte blanche did you get working with big artists like Black Thought, Jay Z or Nas?

Actually all of them gave me a lot of freedom. I think they came to me for a reason, they must have seen something in my work that created trust. I always like to approach projects I do with other artists as a collaboration and they had really insightful observations and thoughts as we were making the films.

So I try to keep my directing style as an observer, rather than dictatorial and so your words really touched me, they’re exactly the kind of words I would want to be associated with. For me it’s all about authenticity – you’re not watching something that feels fabricated or disingenuous. With Bam notably, our approach with the production team was not to cast actors or stage scenes but to do deep research and find the right moments in real life that I needed for the narrative and then capture them.

Let’s go back to the start and how your journey as a film director began…

I would say my career started at Central Saint Martins (Art School) – as I went there to find my way into the film industry, thanks to my secondary school art teacher’s encouragement to pursue that path and my dream.

As there weren’t many cameras available for the whole class I used my Dad’s mini DV camera so I could shoot when inspiration striked, mainly video art at the time. When I graduated I hired a better camera and made a short film to try and get into a film school to do a Masters. I didn’t get in, but around that time the Canon DSLR video era kicked off and that’s when I really started developing and working with artists I knew from my area.

It was back then that I met Pauli and started shooting films for him. A production company spotted our work together and reached out through him, that’s how I got into the commercial and music video industry. I would always strive to elevate my work in some way, to separate it from other DSLR style films.

From Rest in Power, The Trayvon Martin Story

Delving in further, in Rest In Power your promo for docu-series Rest in Power: The Trayvon Martin Story and When I See You, I See Me you did a spectacular job of bringing the artists’ words to life with powerful visual narratives. Do you think works like these are seen and heard in all their dimensions in the wake of George Floyd?

When I first heard the song Black Thought made to tell Trayvon Martin’s story, I knew I had to be a part of this project. I think I wrote the treatment that same day. His words, the music, the cause – I felt it was my duty to make this. It was a very difficult project to be involved in emotionally and I put a lot of pressure on myself to make the film as effective as I could.

I do wonder whether with this “awakening” of society to BLM, works like Rest In Power and When I See You, I See Me will get more attention because I personally don’t think they got circulated as widely as I expected them to at the time. Not that the numbers matter in themselves but those pieces and their messages are so important I hope for as many people as possible to see them.

Wretch 32 at the Tate

From the PR at the time on Wretch 32’s When I See You, I See Me the prominent idea seemed to be about the rise to fame and “trials of modern day celebrity”. But in this multi-layered piece, one may also read the film as an exploration of identity – and notably the lack of black imagery in all the artefacts as he walks through the gallery?

Yes exactly. The title is Wretch saying “I see myself in you and you have the potential to do great things. Where I am now isn’t unattainable.” But from there it became a lot deeper. For example at some point he says, “I see free” – as in I see freedom – but then directly after he says IC3 which is the police code for a Black person.

We both wanted to show him in the Tate Britain as his mere presence there is interesting: Wretch 32 is a true artist of the highest order and his art belongs in the Tate. We were trying to show the lack of non-white imagery and art in that space.

He also plays on the word Tate with ‘esTATE’ – I love it because estates in England are such a hotbed of talent. They’re a melting-pot of people, a community with shared spaces to meet and where creativity is used to get through life and hardship. To me these are the most exciting ‘galleries’, where my favourite artists live and I wanted to show that beauty in the film. We wanted to showcase this idea as it’s something you don’t see in the media when they talk about the estates. I was lucky that my parents showed me that as a kid, and that because you have less doesn’t mean you can’t create beauty and I want kids to know that.

From Nasir

This leads us to Nas – so many of us grew up listening to and loving his music – the work you did with him on Nasir enhances the power of his message to great effect. Can you talk about the process here and what that project meant to you?

I still pinch myself that I got to work with Nas and that’s what we made. I remember being blown away listening to this album, as I always am when I listen to his music. He’s such a story-teller and a historian and from his early works he’s always been brave in tackling tricky subjects. My music video agent at the time asked me if I’d write a video for a song from Nasir so I picked Cops Shot The Kid. He saw it and asked what I would do if I did the whole thing, so I created a video pitch with visual references to build an impression of what I had in mind.

We met up in New York and worked on the different chapters. He trusted me, had lots of ideas, questions and took care in the imagery and symbolism that we were incorporating throughout. This was great collaborative, intentional work and a piece of art with a message. For example I wanted to show a pyramid in the Queensbridge projects to remind us that as Black people we descend from kings, queens and great civilisations that were constructing amazing structures. We shouldn’t lose sight of that. Nas wanted to use a Nubian pyramid as many people aren’t familiar with pyramids outside of Egypt. I could go through more details and layers of meaning but I like to let the work speak for itself.

I wanted each song to be a different chapter that often switched feel or genre: Not For Radio, more abstract, sets up the themes of the film; Cops Shot The Kid and Adam & Eve are music videos; White Label is more a documentary of Nas’ career; Everything is a narrative short film, and Simple Things is more reflective as a conclusion.

For Everything I worked with scriptwriter Ronald McCants. This song is so powerful and it was important to me that the story really hit hard on multiple levels.

I also work a lot with editor Sam Ostrove and over the years we’ve developed a short-hand. He’s great at building tension and exploring stories in a non-linear way. You can see this in the opening minute of the film that explores both the shameful history of America and the lineage of Black people, reaching all the way back to African Empires of old.

From Pauli the PSM’s The Idea of Tomorrow

Story-telling is such an intrinsic part of being human, and film can play a key part in shifting consciousness. What role/responsibility do you think filmmakers carry and where do you see yourself in this mix?

Yes I think we’re all storytellers and deep down we know when a story is told well. I think filmmaking has a central place in modern popular culture and is the equivalent of camp-fire stories back in the day. I personally carry a sense of responsibility with that – what message does your film put out into the world? When I was starting out and finding my voice, I learnt what it feels like to be working on something that isn’t genuine. Sure, some projects could have helped me get by financially, but it just didn’t feel right for me to be associated with them.

Also I am Black and Indian, though how society sees me I identify more as Black and growing up I would look at figures like Spike Lee, Viola Davis, Denzel Washington – what they put their names to and how they carried themselves. I looked up to and respected them and in my small way, I want to do that for whoever watches my work and follows my journey.

Mentoring has always been important to me and since moving to LA I’ve been working with an organization called Youth Mentoring Connection. More recently I helped set up Change The Lens with several Black Filmmakers including Savanah Leaf, Alli Maxwell and Jason Harper. It’s a pledge, soon a wider initiative, to take action in increasing opportunities and representation for Black filmmakers in the commercial and music video industry.

We’ve touched on your sense of purpose through your work, but also your authenticity in finding your voice as a director: who do you look up to or where do you get your inspiration from currently?

I’m a big fan of the artist Kadir Nelson, and also Hayao Miyazaki, Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, Ava DuVernay, Steve McQueen, Gregory Crewdson, Terrence Malick, and I listen to a lot of film scores as they help me visualise ideas. Spike Lee (who I was lucky to meet a while ago) is a big influence – He Got Game and Do The Right Thing are two of my favorite films.

I would also say I’m heavily influenced by my Mother – I get a lot from her, she is brave in her opinions, a well-read person and I think that has rubbed off on me.

I am lucky to be around a lot of amazing contemporary filmmakers and artists. Recently with Centerpiece, working closely with a visionary artist like Maurice Harris was inspiring. He’s a real force, now a close friend and I learn a lot from him.

A lot of my heroes are multi-talented. I’ve been reading “Into the Woods” by John Yorke, as I’m developing my screenwriting ability; I am learning a lot from the writers on my feature projects that are in development.

Director Melina Matsoukas in Centrepiece

The trailer for Centerpiece, your latest piece, is a condensé of pure joy and psychedelia. How did that project come about, and how much freedom did you personally have on this?

Centerpiece was a little different as there was already a proof of concept for it that Maurice and Peter Kline (the showrunner) had been developing with Rashida Jones and Will McCormack. So my job was to come onboard and sprinkle in some filmmaking magic to represent the themes and the narratives being explored. Peter and Maurice included me in all aspects of the series, which is rare for a director in TV. Centerpiece is such a fantastic exploration of creativity, Blackness, identity, excellence and truth on screen – I’m grateful I could be a part of it.

I think I’m lucky with all the people we’re talking about here as they’re all amazing and important artists and understand the creative process on the highest levels. They know that by empowering people, you are going to get more out of them.

In the 1.4 Show we have two directors showcases – Flying High Established and On the Cusp of Greatness for emerging directors. Any words of wisdom to our next generation of filmmakers?

If they’re just starting out, I would say the things in your life you think are a weakness are going to be your strength as a filmmaker. You know when you’re young, “what makes you special” is often what society will use against you, but that’s your truth and your perspective.

I think there are only so many stories and everything is a spin on something that’s been done before, but there are voices that haven’t been heard from enough and I think if you feel like an outsider, embrace that and lean into it. Think about what it is about the stories you want to tell and your voice that make you different – and don’t try to homogenise that because you think that’s what you have to do – lean into that.

Interview by Amelie Lambert

Websites:

See Rohan Blair-Mangat’s commercial work at My Accomplice

Quibi, Centrepiece