David Kolbusz: Autumn, this was an unbelievably quick turnaround from landing the job, to principal photography, to the film’s release date. You’ve made shorts before. Your Prada series The Postman Dreams was a notable triumph. However, to jump straight into a feature from the work that you’ve been doing with these accelerated timelines, seems like madness. What gave you the confidence that you could pull it off?

Autumn de Wilde: I’ve always stuck my head in the fire. Actually the first photo job I had was on a Xerox commercial that Gore Verbinski was directing. And I called up my dad and I was like, ‘Dad, they’re going to figure out that I don’t know what I’m doing’.

I was taught by my father as a photographer, I didn’t go to [film] school and I didn’t realise how much I knew from him. I went to drama school and he’s like, ‘well, you went to drama school, right?’ And I was like, ‘yeah’, and he goes, ‘act like a fucking photographer’ and hung up on me.

I’m 50 this year, and it is my first film, but I have had a lot of trials by fire. It was kind of amazing to not be 21 and wondering how I was going to do it. It was terrifying on a certain level, but I had all these bags of tricks from all these different weird things that I’ve done and they were incredibly useful.

I studied ballet for 14 years. I went to drama school so I know how to talk to actors. I didn’t like being photographed so I used those techniques to help people who also don’t like being photographed. I kind of pretended all of my photos, even portraits, were scenes from movies anyway. The most captivating portraits make you wish that you were there and make you wonder what they did next or what they had just done.

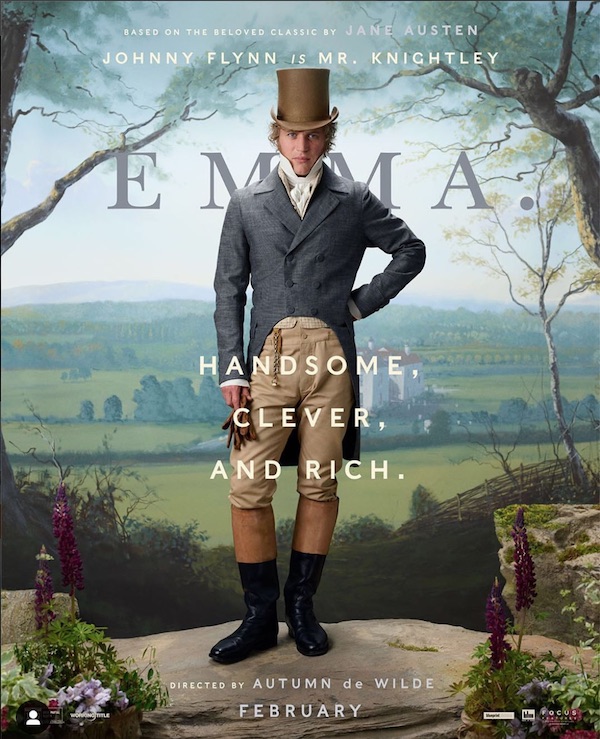

So to help my subjects feel comfortable, I’d often create a movie that never got made for the photo shoot. That is why I think those musicians asked me to do music videos and, of course that worked in commercials. I wasn’t a frustrated filmmaker making commercials, I weirdly really like making them. I had marketing ideas from the very beginning. Like I made a tee shirt that I wore that said ‘Handsome, Clever, and Rich’, and I’m like this is a hook, this is genius. And I had this whole pitch for the film that was based on creative content and the visual palette and all this stuff. It was a benefit that I’d been in commercials.

Portrait for NY Times Mag by @jingyulin_

Portrait for NY Times Mag by @jingyulin_

DK: And a little more on that. The pitch, let’s talk about this right now through the prism of obsession. So you get into things, you become obsessed and it manifests in your work. And one of the wonderful things about Emma is that you just want to live inside this world, as you’re about to see, it’s just meticulously detailed. So please talk about the act of world-building, how it’s integral to your creative process. Maybe you share that delightful little pitch box….

AW: Obviously when I was a rock photographer, not every band was my favourite band that I shot. So I always tried to think from the perspective of the fan, what would they want next? And the same thing with commercials, I always want to know who’s the one that’s already buying it and who’s the person that they’re hoping will buy it.

Then in film I feel like Jane Austen obviously has this set group of fans, they’re going to be in the seats already. And then I wanted to know what would turn someone’s head who says they hate this kind of movie. I didn’t want to go soft and sort of dance in the middle of something. I wanted to commit hard to the Jane Austen film.

I do love period films and I think they’re hard to do well. I’m a fan no matter what. All the research I did was to find the things that maybe have been overlooked or maybe because of the time period when that movie was set, they weren’t comfortable. Like women always looking like they’re going to a wedding in a Jane Austen film instead of the sort of weird tight curls that were the fashion of the early 1800s. It’s so fascinating and comedic. I was like, well I’ve got a funny hook right there that you can poke fun at. If you can poke at fashion, you’ve got another story-telling layer.

I’ve gone off course… Oh the box! Having done so many commercial pitches, I know how often it is just ‘next, next, screen, screen.’. It was always frustrating that I couldn’t be there in person.

I didn’t want them to be able to discuss it over a digital presentation. I thought it would be kind of funny if they were either like ‘fuck that was so good… or so bad’. So I made two of these packages and the box came later for the final pitch. They couldn’t open it until we did our Skype call and then we opened at the same time.

I can’t spread it all out for you. But what I will do is show you a few things. So with my designer I designed a logo basically, which is still the logo..

DK: It’s a hot topic in a lot of the reviews that you kept the period (at the end of Emma.)

AW: Well it’s a period because it’s a period movie.

I have the first page of the book, a design, by my designer and I was thinking about what kind of paper? I feel like everything Jane Austen-ish is like this ugly parchment paper that they never used. You know, these things that in the 80s people decided were Austen-ish. There were newspapers then. And a big part of my pitch was I didn’t want to modernise it, I wanted to humanise it. And familiar, tactile things were part of that.

The other thing I wanted to do is remind people how colourful the Georgian period was. We think of Jane Austen’s world in the early 1800s as we see that period in museums and the great houses in England, which are faded and yellowed with age. But that’s because they’re antique now. And I think everything looks antique in a lot of movies, and I have always been like, no, no, no it wasn’t antique then.

So I’ve exaggerated and heightened the colours, as I like to do with my worlds, show really weird food, fashion, a lot of caricatures, and things I hadn’t considered before, like when the wind blows, this was the first time in fashion that men could see the shape of a woman’s body and how comical that could be or how beautiful and sexy that could be. So that was a big part of my pitch. And also introduced actors that I thought would change maybe the preconceived notion of those characters. I often cast for my pitches anyway, so you immediately can imagine how someone familiar like Bill Nighy would play Mr Woodhouse…

Anyway, so it was a big mess, which was great because then there was spontaneous talk. But each photo (out of the box) was giving me a clue of what we were talking about and it prompted questions – you know, we’ve all been on calls where you feel like you should say something just to say something and just to explain who you are. And I’m just wanting people to talk because they’re actually curious about what I might do.

Click on pic to view designer Carson Ellis’ puzzle purse in action. Similar to the goodies in Autumn’s pitch box

DK: A lot of this feeds into the next question. You’re so meticulous about everything resulting in a very stylized and considered aesthetic which is true of all of your work. But your work is incredibly warm and human and these two things seem at odds. So considering how detail oriented you are, how do you ensure that, that humanity breathes through?

AW: I love a sort of heightened stylized world but none of it works without sincerity and in all my work I die on the sword of sincerity. Maybe not on the concept that I spent all night working on, because sometimes the best idea is the thing next to it, the trashcan that you didn’t know would be on set looks better than the idea you slaved over for two months.

I think it’s important to have a skeleton of an idea, a very elaborate skeleton, always to fall back on. And it’s also important to keep an eye on what’s really happening with the humans around you. As a photographer, I’ve done so much observation with human behaviour, men on tour, women on tour, my own foolish experience, the bands that I shot call me the rock and roll Martha Stewart.

I bring the comfort in the rock, but none of them are surprised I did a film. If the sincerity is there, you can go really big and that’s screwball comedy. It’s such a big influence on this film. I made all the actors watch Bringing Up Baby and His Girl Friday because I think Jane Austen is really funny, but it requires a translation of meaning and an understanding of maybe words that are different now and to know the class system and stuff. But she was a very astute observer and satirist of small town life I think.

I thought American screwball comedy was a really great parallel to exhibit all the things that people want to say, but don’t say. That passive aggressive behaviour that is so beautifully famous in comedy in England because it’s just a part of your life.

DK: Yes.

AW: And I’m a bit like an Italian making a Western.

Autumn de Wilde and Bill Nighy at NY premiere

DK: This was a large cast of characters and a veritable Who’s Who of young up-and-coming British talent. By the same token, you’ve got some legends of the business in there as well too. How did you make sure that every character was fully formed and that everyone worked together as a unit? Because I think when you watch the film it feels like a social circle, a real coterie.

AW: And it was. I had my eye on certain people, like I said, in the pitch. Some of the movie was cast in my head, but they weren’t cast until I’d met them. And I really wanted to form a band. I was thinking about John Hughes’ movies with the Brat Pack and you wondered what’s it like to be with them? Or like ‘I hate them, they think they’re so cool’ or like I’m obsessed with all of them. I wanted that whole thing. And I think that fun is infectious, and I have always built my crews this way too.

I care who the PA is because I think the makeup artist is the first person touching the actors. If you’re not careful about who that person is, there’s this ripple effect, this domino effect of bullshit, bullshit, bullshit. Everyone, bad behaviour. You know, I’m a mom. I have a 20 year old now, and you know if you fuck up. Like if you don’t feed actors and crew, all the dudes at the right time… and I like to make everyone feel important because they are, because it’s this weird fucking circus that should always go wrong with the time limits that we’re in. Right? It is 100% a disaster about to happen unless you really craft the building of the crew and the cast with good chemistry.

I have often not chosen a certain person on the crew because I don’t think they’ll mesh well with that other person. It doesn’t mean that I would never hire them again. So the whole movie was less a bigger crew than I’d ever had, but it was kind of exciting to have producers that believed in the approach and it worked. They all loved each other and I think the fun was infectious, they’re kind of like the Brit Pack instead of the Brat Pack.

I didn’t want them to have a situation where they might be competing against each other. We were doing physical comedy, like Josh O’Connor had done comedy on The Durrell’s but he had never done real screwball comedy like we were doing. He plays a very comedic character and I wanted everyone to feel safe in that environment.

Bill Nighy is like the ultimate ringleader to make actors feel loved and safe and be adventurous because he’s so humble and great. So yeah, it was really an important part of the production and post production as well. It’s the talent and the reel, but also the personality. Everyone just flourished with each other and I think that’s an important creative force.

Links: