You grew up in both Iran and the US; did you always know that you wanted to be a filmmaker – what was it about the creative industries that appealed?

My parents are both artists who left Iran in the aftermath of the revolution during the Iran/Iraq war. We were forced to leave our country and like most asylum seekers, we were in limbo as we waited to be assigned a new home. Eventually, we got our visas and moved to San Jose, California, entering the bottom of the socioeconomic barrel.

I grew up in a housing project and we relied on food stamps for the first few years. I watched my parents struggle to reinvent themselves and find their place in the States. But in truth, I don’t think they ever truly found it here. As a kid, you just absorb and accept all of this; you tend to piece it together, the older you get.

You could see Silicon Valley from our backyard, so the extreme polarities of my community were always apparent and felt; but they acted as a catalyst for me to explore concepts of imperialism, class struggles, and institutional and systemic oppression. It also cultivated a beautiful resilience within me.

One of the truest clichés is that great art is born from struggle and pain. I’ve explored narratives about the uncompromising strength of disenfranchised individuals. Often, my stories feature subjects creating something for themselves despite the odds stacked against them and in doing so, they’ve held a mirror up to society in a most unrelenting yet revealing way. They also help me to make sense of all that I’ve encountered.

You’ve developed a very strong filmic style. What do you love most about creating your own projects?

I was always more influenced by images and music than the written word. I spent a lot of time listening to albums while going through my favourite photography books and magazines; it made the images come to life and feel as if they were moving. The music would almost act like a score to the process. I think of it much like Disney’s Snow White, where the film starts and ends with a book opening and closing – it was a similar experience flicking through my books with an album on in the background.

I still love to play music while I look at images; it fuels my ideas and helps me process my visual language. In this last year, I revisited a lot of Roy de Carava’s work at the suggestion of my friend and photographer, Ike Edeani. I went to The Underground Museum in LA to see his images and took them in while listening to Jaime Branch’s Fly or Die album through my headphones. It was magical. And those sensations stayed with me until later that night and the next day. My psyche was captivated – I remember having dreams inspired by the experience. Unearthing new art is important to me; it helps deepen my sensitivity and push my creativity… I’m currently into pre-revolution Iranian pop.

A lot of your independent work is rooted in documentary. How do you strike the balance between sensitivity and hard-hitting realism?

I’ve thought about this throughout my career and think that it started in childhood, where I was a pretty sensitive and scrappy kid, who got into trouble repeatedly during school. In seventh grade, I had a PE teacher who gave me an ultimatum – either I would be suspended or I had to attend a regular wrestling class after school… Of course, I decided on the latter.

Wrestling quickly became a passion of mine. It’s a brutal sport that forces you to face yourself and dig into uncomfortable places personally. What you realise is that when faced with challenging obstacles, you’re confronted by what motivates you.

A lot of what I’ve learnt through sports, I apply to filmmaking. Before I take on any project, I center myself and think about what’s pushing me to tell the story. That way, I can keep that in mind when the mental, emotional and spiritual fatigue inevitably sets in. In the long-run, it’s all about endurance.

Once my motivation for the project is clear, I share it with the actor or subject I’m working with. That way, they can understand my intentions and see what we’re trying to achieve. Storytelling requires high stakes and tension; so, I work hard to identify these aspects and focus on presenting them as needed within each piece.

It’s not uncommon for an actor or a subject to share something with me that they’ve never told anyone else before. I encourage honesty and truth in my work and try to create a safe space on-set for people to open up in.

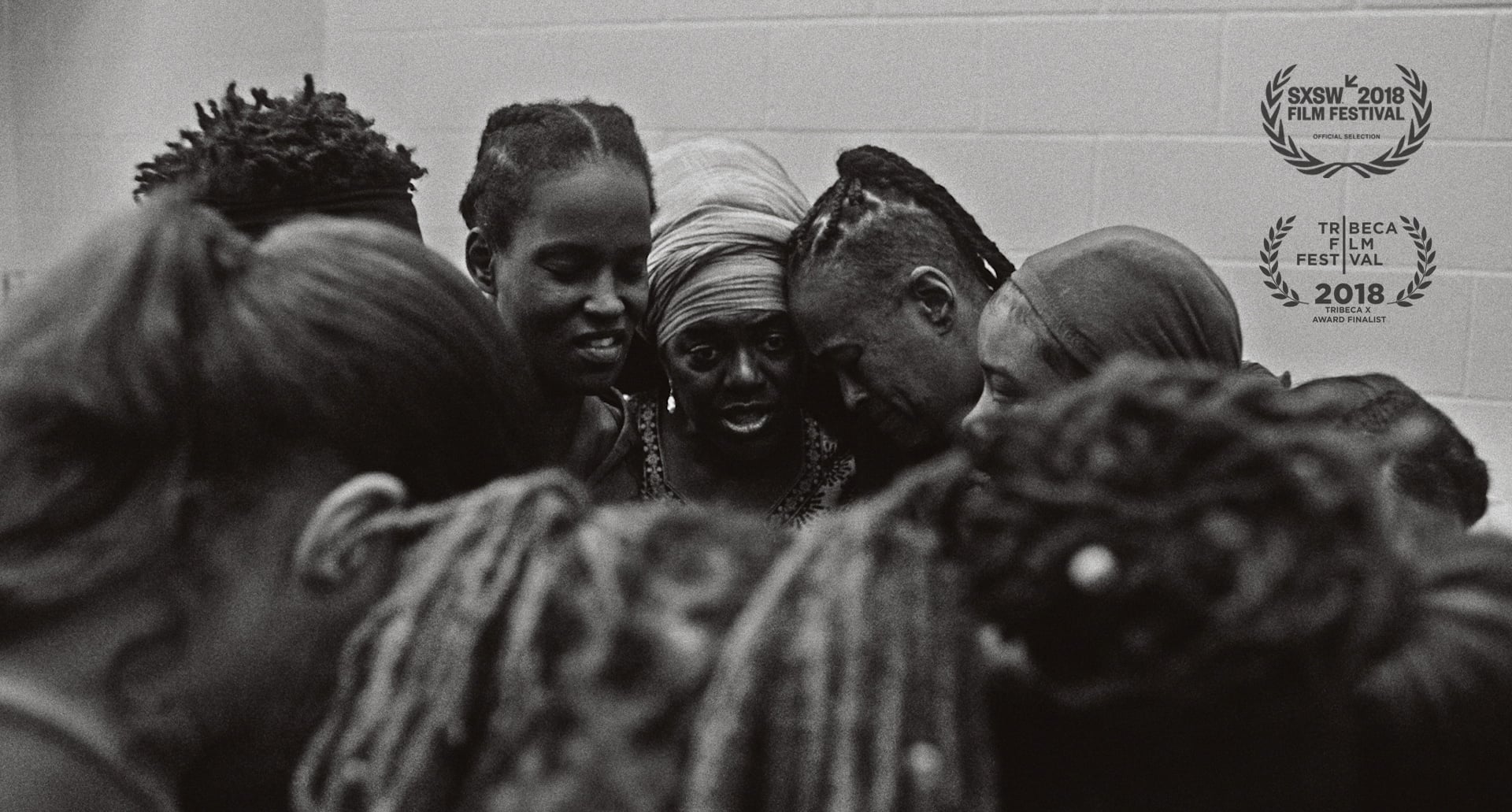

Sister Hearts

How do you find a lot of the protagonists that feature in your work?

Even/Odd [the production company launched by Gorjestani and filmmaker Malcolm Pullinger] is not just a creative studio and a production company; it also has a research element to it. We have between two and four researchers constantly working on any one project, exploring various subjects and pursuing leads. Our core team is deeply curious and we’re all on the same page when it comes to the sort of work we’re passionate about making.

What inspired you to make the highly-awarded Exit 12, Moved by War short?

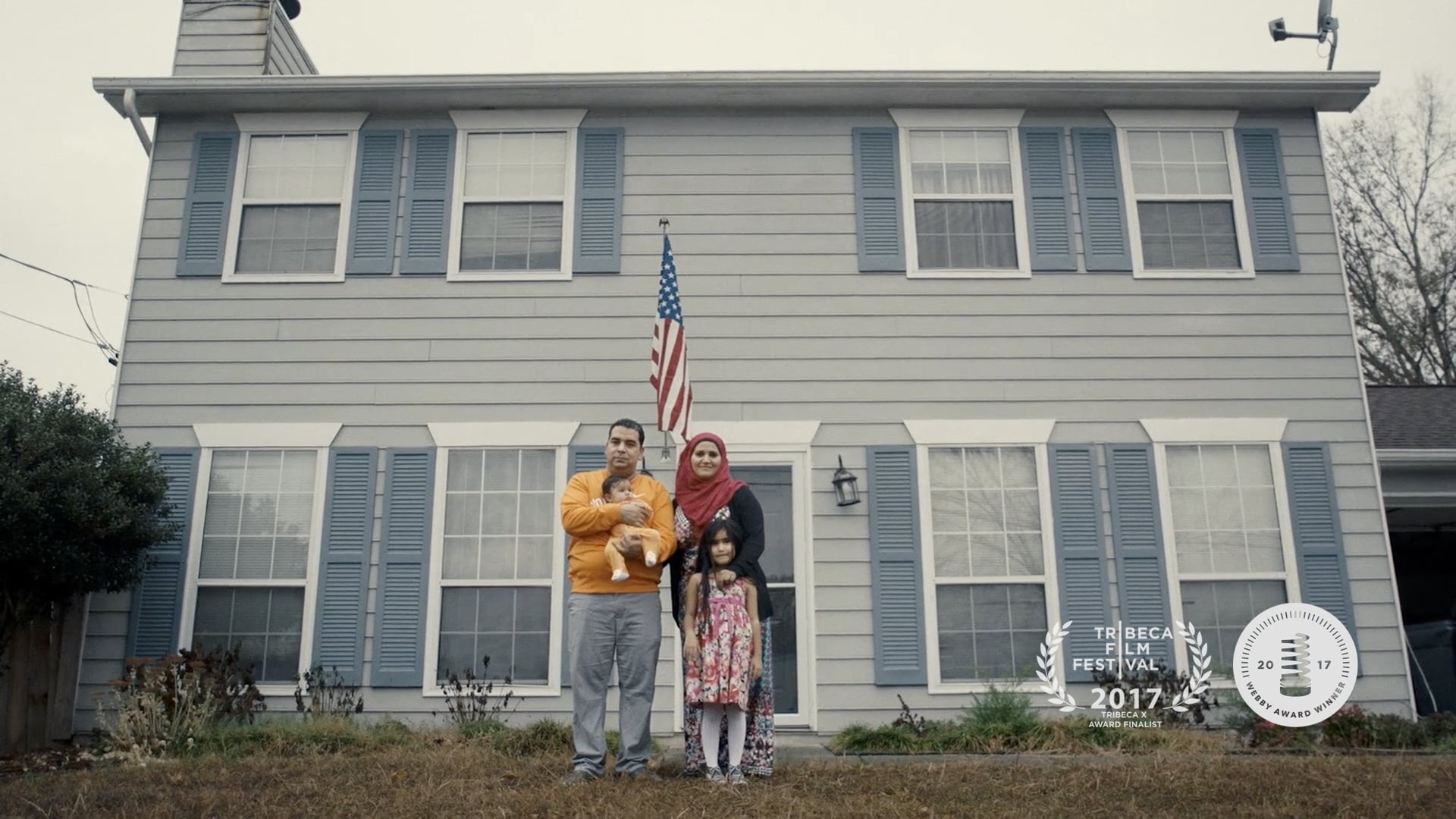

Exit 12 was part of a larger film series commissioned by Square that examines how class struggles have affected the contemporary American Dream. Each film focuses on communities and individuals that have been disenfranchised yet risen above the hardships they’ve experienced. Our partners at Square – Justin Lomax, the series EP, in particular – and I felt that we needed to include veterans in this anthology for a fuller and more accurate picture of who this was impacting.

This film also acts a countervoice to the current discourse in America. There are many people trying to rewrite American values today and hijack what it means to be American. They tend to steer public opinions on patriotism and include veterans in this mix.

Like many Americans, I don’t feel represented by politics right now. It felt powerful to infiltrate this conversation using a veteran’s viewpoint; they’re the undisputed vanguards of American morality and tradition. By showing a veteran in an alternative way to the image that’s promoted in the media, we’re challenging the notion of what constitutes strength and Americanism, forcing viewers to reassess their prescribed values. Exit 12 attempts to remind viewers that acceptance, diversity and inclusion are important qualities for American veterans.

Right now in America, if you’re an immigrant from a community that’s been marginalised by the current administration, you can’t help but question your place here. The film was also a chance for me, as an Iranian-American filmmaker, to contribute to the conversation and provide an alternative stance on the veteran community – one that shows them as simultaneously patriotic, sensitive and compassionate.

What do you think was gained from using Roman Baca’s voice for the narrative rather than featuring the face-to-face interview?

I didn’t want to take a camera in when I was interviewing Roman; I wanted to create a really intimate setting in which to record our interviews, which is only made more difficult with a camera. In our conversation, it’s almost like we’re chatting over coffee; it’s that tight and clear. Roman’s voice acts as a guide throughout the film and doesn’t break the fluidity of scenes. I considered including a talking head of Roman at some point – so that it felt like we were coming close to breaking the fourth wall – but the aesthetic of the film was poetic and ephemeral, so, in the end, it felt right to leave that out.

You also use dance throughout the piece to show his experience of war; why do you think this is such an effective vehicle for pushing the story forward?

The entire premise of the Exit 12 Dance Company is to show that conventional methods of coping with the effects of war don’t always work. The film has two languages – English and dance. Dance conveys what words cannot; and when relaying the experience of war on-screen, there were moments where we couldn’t rely on words to structure the film’s narrative and message. We needed dance to help the audience understand what Roman and the other protagonists – Angela Scimonelli, and Everett Cox – had experienced. The dance company teaches veterans that movement is vital for undoing the effects of war as it can help to release whatever is buried inside. Dance heals by providing a new language to communicate traumatic experiences to others.

Why did you decide to use captioned chapters to structure Exit 12?

This decision helped to show the impact that the Exit 12 Dance Company had on its participants and in particular, on the three characters portrayed. It also meant that we could show how war has impacted people across generations.

Roman served in the Iraq war and represents the post 9/11 experience from a soldier’s perspective; while Angela reminds us that war affects more than just soldiers; and Everett, a veteran of the Vietnam War, reveals the lifelong effects of war on the spirit.

For each storyline – which is consistent with how Exit 12 creates its dance pieces – we examined each character; interviewed them about their experiences, then watched as they interpreted their memories through dance.

What was it like filming the veteran dance class? Tell me about the atmosphere of that session?

It was powerful. I watched as a room full of veterans opened up, expressed their horrors and healed themselves in real time. We were so fortunate to capture that. There aren’t many people who have seen veterans act vulnerably without appearing helpless on screen. They really took control of the adversities that had taken place throughout their lives and redefined it in front of us to show the strength in humanity and our inherent sensitivity. It made me appreciate the power of art and dance, especially.

You’ve also worked on some commercials and a filmic series as well as adapting one of your shorts into a feature film. What’s next on your agenda?

I have a couple of projects I’m working on, but I’m really excited about developing a narrative feature based on my film, Refuge, which came out in 2014. It’s a timely story about immigration, diasporas and class struggles set in the near future as a cyberwar erupts between the US and Iran. I’m looking forward to expanding it.

Interview by Olivia Atkins