What was the process for selecting moments from the 50 years of Gay Pride evolvement into two minutes?

This was a constantly developing conversation between myself, the creatives, and the team BMB, Pride in London, and also LGBT+ friends, family and collaborators. As you can imagine, it was a big conversation! Eventually, though, as a director, you need to steer that conversation, and make decisions.

I had several criteria by which I judged any event and whether or not it would work for the film: first of all did it demonstrate agency on the part of the community? We wanted this film to feel like a battle, with victories and setbacks. Secondly, was it visual? There were some shocking milestones that we discussed (like: ‘1992, the World Health Organisation declassifies Homosexuality as a mental illness’) but they weren’t necessarily cinematic (although we did do a lot with audio to make reference to more than just what you’re seeing on screen).

Finally, was this event representative? Alongside hoping that the film would depict a coming-together of the LGBT+ community, we also wanted to ensure that different groups within that community had their individual stories told. That was really important to us, and to the client.

Did you personally research the events or did the client brief you in detail on key issues?

We began with a list of events, as I’ve described, which evolved into a script. Broadly, all of these things were already known to us – Stonewall, the AIDS crisis – but as it became increasingly clear which scenes would be the ones to be filmed, I started my own process of research – academic and personal – into those events.

There were certain books which were invaluable for some of the older events: Randy Shilts’s massive And the Band Played Onwas very helpful to me in understanding the intricate medical and emotional horror of AIDS.

There’s also an amazing recent book called We Are Everywhere, by Leighton Brown and Matthew Riemer, which is a visual history of queer protest. Given that Protest is central to the film, that became incredibly useful.

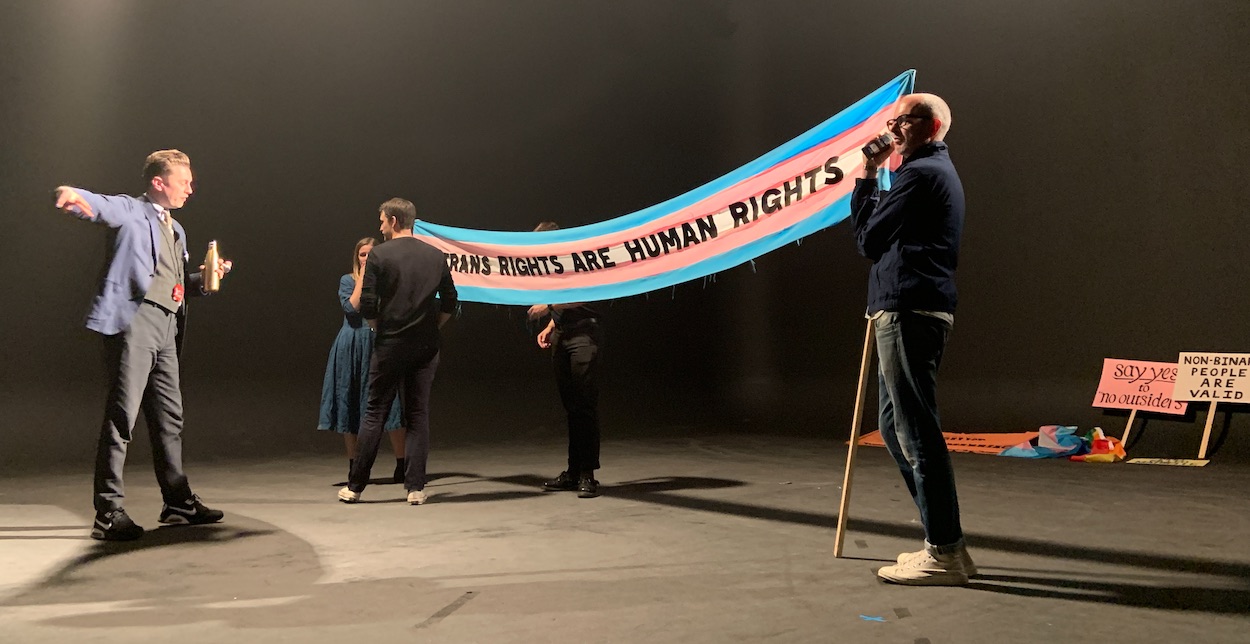

Mainly, though, my research was conversations with people who had either lived through the events depicted, or – for the more recent scenes – are still living through them. Conversations with Trans activists informed how we wanted to stage the final moments in the film, and conversations with queer friends and colleagues led to decisions such as how we wanted to cast and portray events like the legalisation of gay marriage.

The level of subtlety and sensitivity required for each scene meant that this kind of in-depth personal research was absolutely essential.

Behind the scenes: distilling half a century of Pride Protest

Straight man in stunning suits – what was behind the decision to give a non-gay director the job?

This was a question that I wrestled with throughout the process, and very much so at the beginning, when I was initially pitching and committing myself to the job. The last thing I wanted was to take ownership of a story that wasn’t my own. I know I wasn’t the only director on the table, but perhaps what made our treatment ‘the one’ was Blink’s commitment to an open and collaborative approach to creating this film; an approach which openly factored in not just my creative opinion, but the opinions of many different people from the LGBT+ community.

Making the film from that perspective, and populating our crew with LGBT+ talent, was the only way that we felt it could be done. Further to that, on the Blink side of things, I worked in extremely close collaboration with my EP, Paul Weston – who is gay – who had a big hand in formulating the script, and who pushed very hard for Blink to do this job because this is an important story to tell – especially this year, given recent events.

It’s really important to acknowledge (especially on a blog which celebrates the craft of directing!) that, as a director, you are only one piece of a much larger tapestry of people, all collaborating to create a final product. In the case of our film, no single person, whatever their background, can have ownership over this multitude of stories and events. Ultimately, I have to acknowledge that this isn’t myfilm; it belongs to the community for which we made it, and it exists in order to provoke and educate the people who aren’t perhaps aware or appreciative of the struggles depicted. Judging by the response from Pride, and the wider LGBT+ community, I hope that we managed to achieve that effect.

p.s. I’m glad that you noticed the suits – I always wear a tie on set…

The Thatcher speech was a timely reminder of how loathsome and shocking some politics were. Also the placards must have kept the art dept going for a while.

I agree – and that’s why we included it, along with some of the more period-correct, but politically in-correct placards that you might spot in the 70s scene. It’s worth noting that, throughout the production I, my crew, and my cast had to face the reality of some truly shocking prejudices and injustices in the events that we were depicting. Hopefully some of the emotional edge of the film is down to the fact that we didn’t shy away from the darker parts of this history.

What were the biggest challenges of the whole production?

Oddly, for what looks like – and was – a huge undertaking, the production ran incredibly smoothly. I think that everyone involved had the sense that we were shepherding something very important, and so the conversations and decision making processes were much more open and honest than they can be on some other commercial jobs.

The creatives at BMB, Ben and Alex, their CD Matt Lever, and our excellent agency producer Jessie Gammell entered very happily into this collaborative atmosphere, which was really refreshing and truly benefited the film. By nature of the fact that many people were giving their time either for free, or for a token fee, the biggest undertaking was just the fact that I had to spend a lot of time by myself working out things like complex camera moves and edit transitions where, usually, those would be group decisions. Luckily, I had an extremely talented crew who were able to fill in the gaps that I’d missed and bring it all to life!

What was your criteria for the cast and where did you find what feels like a cast of thousands?

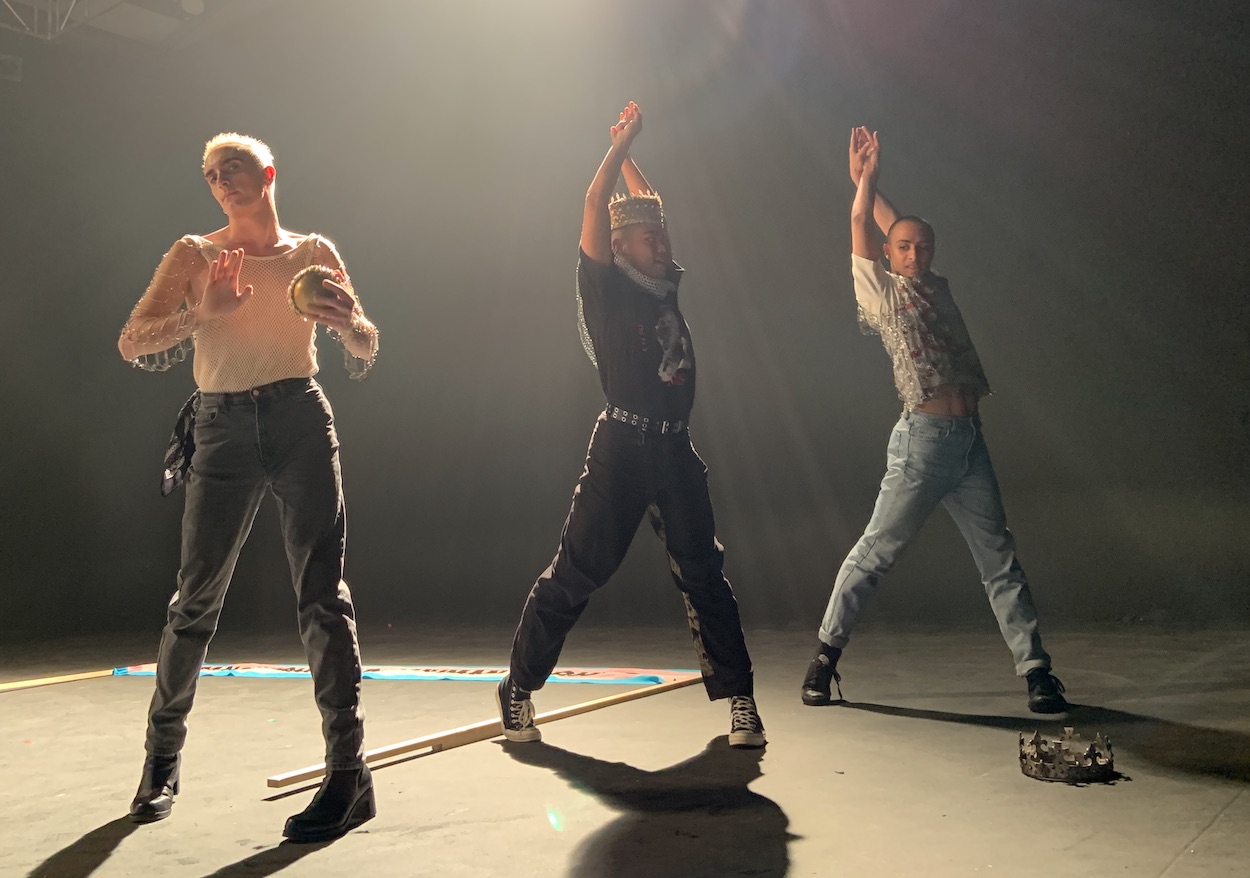

Our main casting criteria – above all else – was that the people on screen had to bethe people they were depicting. There is nobody in our main cast who, had they been alive at the time of the events, wouldn’t have been undergoing the same experiences as the characters. There was never even a conversation about any alternative approach. Had one been suggested (it never was) we wouldn’t have done the job. The tricky part came in doubling up our cast members. The effect is surprisingly subtle, which I didn’t think it would be until I met Kirsten Chalmers, our amazingly talented head of hair and make-up. But the idea was to give the sense of a theatrical troupe of actors, and have lots of performers reappear in different roles throughout the film.

It’s a testament to Kirsten’s work that, in many cases, you don’t even realise that you’re seeing the same person twice. This decision came partly from budgetary reasons, but also because we felt like it was a great way to depict the accumulating momentum of the queer rights movement. So what began as a practical solution to a budgetary problem became something much larger and more powerful.

Is there anything else you’d like to share?

I’d just like to take one more opportunity to thank our crew and cast for all of the passion and focus that they bought to this project. I think it truly shows on screen, and it made the job a thrilling experience to work on. It’s also worth mentioning that this is yet another collaboration with my long-time producer Corin Taylor, whose genius has been behind almost all of my bigger jobs in recent memory (Palo Santo and giffgaff, to name just two) I’m very lucky to have him!

LINKS: