Fred, what was your process of writing the narrative and treatment – did you feel you had clarity about where you were going from the get-go, or did the script evolve in intense fits and starts?

There was a lot of fitting and starting, and ‘intense’ is definitely the right adjective! It’s funny because, as I’m planning the next instalment in the series, I’m going back over some of my original ideas that Olly and I discussed, to see what could be recycled. All we had at the start was: a sci-fi world, in which society revolves around entertainment, and the concept of gender has faded from memory. So, to be fair, that’s pretty much what you have on screen, but there are lots and lots of things that got left by the wayside, like – to name a couple – a decades-long dust storm which meant that there was zero visibility, and that people were covered in filth every time they went outside – and a concept of people possessing one another and transforming in a blur, into someone else.

Were there moments when you thought the film wasn’t working at all?

Not exactly, but there was definitely a feeling of sewing the parachute after we’d jumped out of the aeroplane. It got signed off as a treatment, but we had no script. And we had a brief to make two music videos (Sanctify and If You’re Over Me) which would fit into the film somewhere, but just be single scenes. So, alongside prep in the UK, I had about a week to write the script – usually I like to take much, much longer on a screenplay that would end up being a third of the length of Palo Santo.

This time I was in collaboration with Olly, his manager, Martha Kinn, and also Blink’s Paul Weston, and the four of us had several story conferences to make sure it was working. But it was tricky! I also had to design elements of the film – like the dance sequences – to be multi-layered, so that they could be used to tell the story one way in a music video, but another way in the film, without overloading our shooting schedule. So it was like a giant emotional jigsaw puzzle, with no moment to step back and critically assess whether the script would work. Which meant that I had to go and shoot it as full-throatedly as possible and then hold my breath and wait for the edit.

Was it a harmonious process collaborating with Olly Alexander?

Always. There’s often a sense, in the world of videos, that a director only has one chance to get an idea right – and if the artist or commissioner feels that the treatment’s not quite there, then that’s it. This was the exact opposite, not just because Olly and I had long meetings talking about the world of Palo Santo and experimenting with ideas, but because Olly is such a thoughtful and generous collaborator. He’s got a great skill at teasing the best ideas out of me and refocusing me when I was going off on a tangent. We also share the gift of not being too precious – we dumped a lot of ideas, with no remorse, before we settled on the right one.

The production feels big budget – was it?

That depends who you ask! The size of a budget is always a matter of perspective. I think that the size of the budget ultimately reflected the esteem in which the label holds Years & Years as one of their major pop acts. And, as for it feeling big budget, I always saw this needing to feel like blockbuster filmmaking: grand scale and big emotions. Not esoteric. The top 5 acts in the charts – which, right now, is Years & Years – are the music world’s version of The Avengers or Star Wars. I wanted our film to reflect that.

How did you go about finding the locations and sets in Thailand?

We were lucky enough to have on board the services of an excellent production company based in Bangkok, called Indochina Productions. Their main work is commercial filmmaking and feature films (they worked on Kong: Skull Island). So they found the locations ahead of us arriving. We were blessed, in that they really understood the creative and devoted themselves to enhancing it. I’d say 90% of the places that you see in the film were the first locations that they showed us. That, and their dedication to the story, was rare for a service company.

What were the main challenges for you during the production?

Time and energy! As always. But particularly so here. It was a very long (4 day) shoot. Preceded by a tech recce that ran over two days, but which easily added up to 26 or so hours in total. So we were battling against heat and exhaustion, but it wasn’t too bad because we knew what we were getting into. I do remember on our day of shooting the big dance sequences, we walked onto set pretty resigned to the fact that we weren’t going to get everything …but we did.

How did the film change in the edit? Were there extra scenes that were cut out or did you need to pick up shots or did everything hang together with the material you got?

It’s a boring answer, but it came together as planned – more or less. There was one scene – the moment where the androids recharge on the steps – that floated around a bit, like, we weren’t sure where it was going to live but we knew it had a place in there. Unsurprisingly, one element really, really helped: by the time we recorded Judi Dench’s narration, we weren’t too far off picture lock and were feeling like ‘okay, this isn’t going to be terrible, it actually works’. We sent our recordings ahead of us, and by the time we were back in the edit, Sacha, our editor, had already layered them onto the film. That was a big turning point, when we realised that we might have gotten away with it…

Is there anything else you’d like add?

Just a massive thank-you to a few people. Olly and I are both very lucky to work closely with Years & Years’ manager Martha Kinn who, aside from being machine-like in her determination to get the film made (alongside, you know, getting the whole album finished, promoted, etc.) is a creative force in her own right, who came up with a lot of scenes, details and emotional beats in the script – especially helpful in the moments when Olly or I were feeling a bit lost.

Corin Taylor and Paul Weston, too, for much the same reasons: not only did they go above and beyond their roles as Producer and E.P., they also have an indispensable creative eye, and contributed key elements to the film… as well as making the whole thing happen.

…and then finally, a thanks to my favourite DoP, who I was lucky enough to tempt out to Bangkok: Jaime Feliu-Torres. He shot my very first film for me, when I was 19, for no money, and he has stuck around ever since. I like to wonder how we’d have felt if, knee deep in a rat-infested river in Catford, shooting one of my bizarre suburban tales, we could have had a sneak preview of where we’d end up.

Edited transcript of Munroe Bergdorf’s interview with Olly Alexander and Fred Rowson:

Munroe Bergdorf: The video has so many undertones. How much of it reflects society?

Fred Rowson: All of it!

Olly Alexander: We wanted to make something that you could watch and feel like, “Is this a commentary on what’s going on?”. I love an ambiguous piece of work. I wanted people to infer their own thing.

Fred Rowson: I don’t know if it’s laugh-out-loud comedy but we always wanted it to be really fun to watch, and not feel like you were being force-fed a message.

Olly Alexander: Exactly.

Munroe Bergdorf: It’s very emotional.

Olly Alexander: I find it more emotional than I expected it would be.

Munroe Bergdorf: How do you feel seeing yourself up there?

Olly Alexander: It’s quite intense. My face is so big. I dunno, I loved it. It was such a magical time, we went to Thailand to do it. If I could explain to you the monumental feat it seemed to require….

Munroe Bergdorf: How did it all start? How long has the timeline been?

Fred Rowson: We officially started to properly do it around Christmas. I had written up an idea, then sent it back and forth to Olly. We were always talking about two videos and always knew they were going to be connected, and then at a certain point Olly was like, “Yeah but we’re not making a film yet.”

Then I said, “Well hang on, why don’t we also make a film and connect the whole thing?” We knew that we wanted the videos to tell a story, so why not go the extra mile and add something where the videos work by themselves, but the film adds that extra layer. So, after Christmas I went away and wrote that film. We sent it backwards and forwards, and tweaked it and changed it, and finally said, “We’ve got two days before we fly into Thailand so this has to be it,” and it worked out.

Olly Alexander: And we did it in four days? Five days?

Fred Rowson: We shot the whole thing in four days.

Munroe Bergdorf: Four days! And the iconic Judy Dench? How did that come around?

Olly Alexander: I met Judy Dench a few years ago in a play and I’ve been trying to get her involved in a Years And Years video ever since but it’s never really worked out, and then this time . Fred and I were talking about an omnipresent voice like the Wizard of Oz that’s blared out in Palo Santo to tell the androids how to feel.

Munroe Bergdorf: How to think.

Olly Alexander: Exactly. When to charge by the moon. And we thought Judy would be so perfect for that.

Fred Rowson: We were in an alleyway in Bangkok at about midnight, dripping with sweat, really, really wanting to go to bed and Olly got a message from Judy’s assistant saying, “Yes, she’s really up for it,” so that was a good pick me up.

Munroe Bergdorf: Also, I’m loving your knees.

Olly Alexander: Oh, thanks!

Munroe Bergdorf: I haven’t seen them since the first video, Sanctify, but how long did that all take to put together, because it seems there’s some very serious choreography you’ve got going on there.

Olly Alexander: Well, we worked with a very good choreographer, [Aaron Sillis ], who’s in the building right now.

Munroe Bergdorf: It feels like that whole Christina and Britney era of the Naughties, ‘Baby Come On Over,’ that kind of thing.

Olly Alexander: But in space.

Munroe Bergdorf: But in space. And a more sexual Britney.

Olly Alexander: Well, basically before we shot anything we had a few days together with Aaron Sillis in the studio and he’d play some music and said, “What can you do? Freestyle. Do a trick! Do something.” And I was like, “What about this? What about this?” And he half based everything on that.

Fred Rowson: We had four hours of rehearsals.

Munroe Bergdorf: Four hours? Wow!

Olly Alexander: Oh, because we ended up doing it differently at the very end.

Fred Rowson: Quite last minute.

Olly Alexander: It was quite last minute, yeah. And Jacob came out with us as well. He’s sat next to Aaron. Can’t see him but he’s there. He plays I guess my love interest in the video.

Munroe Bergdorf: I think on purpose he became the love interest.

Olly Alexander: No. No, we weren’t allowed to bring any people over so it was … yeah, work, such as it was.

Munroe Bergdorf: So having to perform over and over again for an audience of androids, is that how Olly Alexander feels sometimes? (laughs)

Olly Alexander: Well, maybe sometimes but I think watching it, and I see how the visuals come together and the storyline and everything is stuff that I’ve been obsessed with ever since I was a kid and I’m obviously a performer and I’m really interested in how we change identities on and off stage, and the tension between that and when you do something you love like you’ve dreamed about all your entire life, it’s not always as sweet as you would like it to be. Obviously I’m not being forced to perform by an android.

Munroe Bergdorf: Not literally anyway.

Olly Alexander: Not literally.

Munroe Bergdorf: So many lovely things in there though about accepting people and I liked the lines, “What do you look like underneath your clothes, much like you probably.” It felt very child-like, examining each other’s bodies. How did the ideas come around or who wrote the ideas?

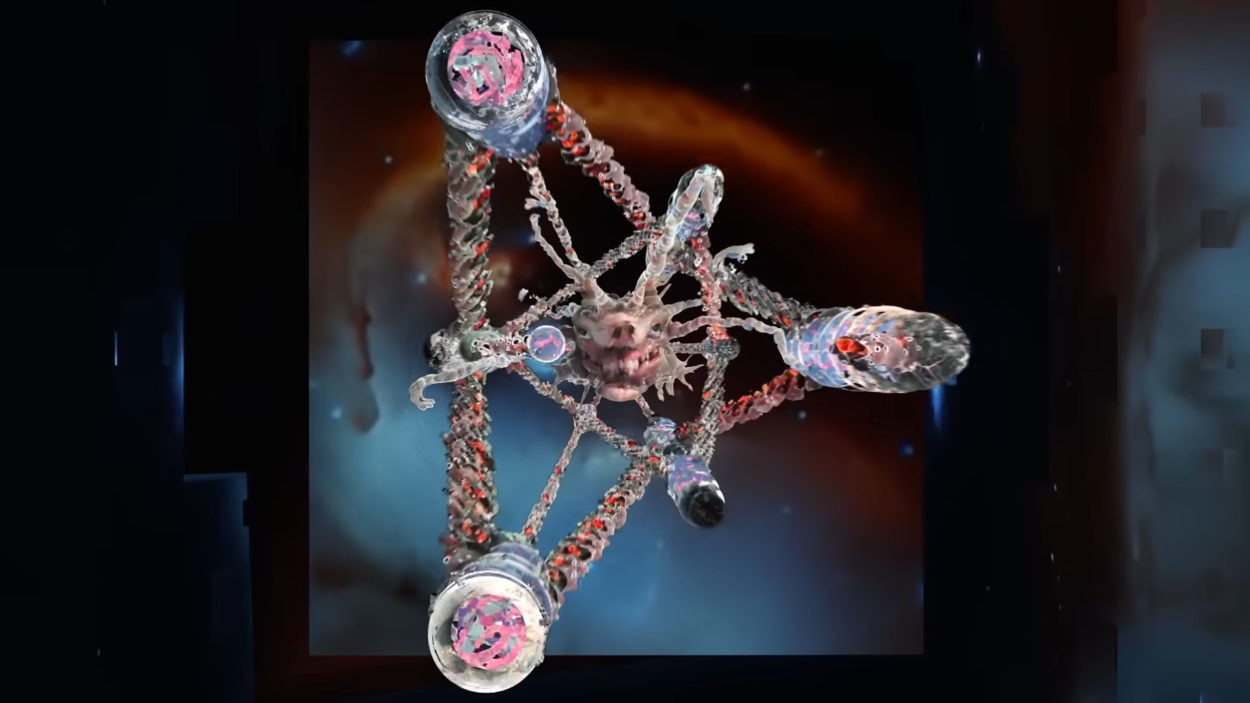

Olly Alexander: Well, I always wanted there to be… sorry, I’m talking a lot aren’t I? One of the reasons we ended up with androids… because we went through loads and loads of different ideas, didn’t we, and then ultimately we ended up with androids and an android society and what we liked about that was imagining what android sexuality would be or what an android’s gender would be or how they would view human sexuality. We could completely step outside of all normal society.

Fred Rowson: It was to do with emotions. We were interested in what does it look like when you perform in a very emotional way and you get no response, and how does that make you feel? It’s that we wanted to have these scenes where Olly’s performance on stage was being interpreted by an audience in a very bizarre way, to make it feel a little more uncomfortable. A lot of the film, and that scene in particular with ‘what do you look like under your clothes,’ was designed to make people feel a little bit uncomfortable.

Olly Alexander: Yeah to feel like, “Are they gonna fuck?”

Munroe Bergdorf: It’s very emotional when the Android Ten gets decommissioned.

Munroe Bergdorf: So there’s lots of symbology obviously, and I’ve been seeing your Instagram and it’s very spiritual, so how did you come up with the name Palo Santo?

Olly Alexander: Oh, well, I wrote a song called Palo Santo a couple years ago and the song was inspired by this guy I had a weird love triangle situation with him and his partner and he was burning these sticks of Palo Santo and I’d never encountered it before, and I love anything that smells good and burns –

Munroe Bergdorf: Will there be a Palo Santo 2?

Fred Rowson: We’re figuring out what happens next.

Olly Alexander: Yes is the short answer, but we don’t know quite-

Fred Rowson: Well, we’re working out where it goes from here. It’s going to go somewhere because we’re going to do another video.

Olly Alexander: There’s a lot to see, don’t rush it.

Munroe Bergdorf: What can we see from you next?

Olly Alexander: Our album’s coming out and we’re touring and making more videos with this one.

Fred Rowson: That’s right, that’s all I’ve been doing all day. In Years and Years world, listening to the next song and pulling my hair out thinking, “Where’ll Olly end up after that?”

Olly Alexander: And we’ve taken this film as the inspiration for the live show… we’ve done it a couple times already but we’re still creating it…

Munroe Bergdorf: When’s the next big performance?

Olly Alexander: The next? (laughs) Well, we’re playing The Round House on the 9th? 10th of July, so we’ll be there.

Munroe Bergdorf: Amazing. If anyone’s got any questions stick your hand up.

Audience: Why did Android Number Ten get decommissioned?

Fred Rowson: Because everything comes to an end.

Olly Alexander: It’s like you don’t really care about the androids because they don’t have any emotions and they’re robots so you can’t, but then you do. Actually, my mum asked me that earlier and I remembered that we had some different versions of the script where different things happened.

Fred Rowson: Different awful things.

Olly Alexander: Different awful things to Android Number Ten, the showman, because we had all these different theories about maybe androids have a shelf life where they only live for six months and then they have to get changed, or maybe he had done something that was against android code because he was falling love with me so they were like, “No, he must die.” In the end we wanted to leave it open.

Fred Rowson: Yeah, it’s ambiguous, but everything comes to an end.

Munroe Bergdorf: I thought it was very nice that Android Ten was becoming a little bit more human as well. There’s these parallels between humans and androids and it felt very bitter.

Fred Rowson: It’s learning which emotion fits which situation. He felt the right emotions at the end.

Munroe Bergdorf: Do we have another question?

Audience: I was wondering about the influences, the inspiration….

Fred Rowson: The Muppets. Mulholland Drive.

Olly Alexander: I can’t think what else.

Munroe Bergdorf: I’m getting some Blade Runner in there.

Fred Rowson: There’s a bit of Blade Runner, there’s always a bit of Blade Runner, you can’t recycle without Blade Runner.

Munroe Bergdorf: I really loved musicals like Chicago and some light Bob Fosse like…

Fred Rowson: All That Jazz.

Munroe Bergdorf: Yeah, but generally a love of science fiction as well like Fifth Element, Star Trek.

Fred Rowson: Showgirls was the really big one.

Munroe Bergdorf: It really was. Showgirls in space.