Why Tibet?

The non-profit institution “Brontosauri v Himalajich” (The Brontosaurs in the Himalayas) has worked in Little Tibet since 2009 in a village called Mulbekh. They built a school there and every year volunteers come to share their education with the locals and in return the locals teach the Czechs Buddhism, meditation and about their deep connection with nature. There is nobody higher or lower in this relationship – it is an equal partnership.

At the end of last year the director of the organisation came to me with an idea about a project to introduce Czech hockey to Tibetan children.

The winter in Little Tibet is very severe and due to this it’s not possible to heat the school. Therefore schooling is interrupted for four months, during which boredom becomes a real problem. The older ones fight it for example with alcohol. The Brontosaurs decided to build an ice-hockey pitch in the village and bring Czech trainers to teach the children to play ice-hockey.

The project is planned to run for five years and its purpose is to keep the children busy to deter them from negative behaviour. The secondary motivation is to raise an Indian national team and a new generation of ice hockey players in Mulbekh.

Our mission was to create a video that would raise public awareness of the project in the Czech Republic. And I think that has been achieved. The reach of the video on social media was around 1 million people.

How did you win over the cast to perform in your film Jágrlama – you’ve managed to get very natural performances from them. Did you get to know them for some time before the shoot?

The way we chose the actors was very similar to a usual casting. There was one man who had a crucial role in the production process – Samphel Tsering, a builder in the Mulbekh village. He was a local character who knew every corner of the village and almost every resident and he organised a meeting with a bunch of locals. We chose our heroes from them.

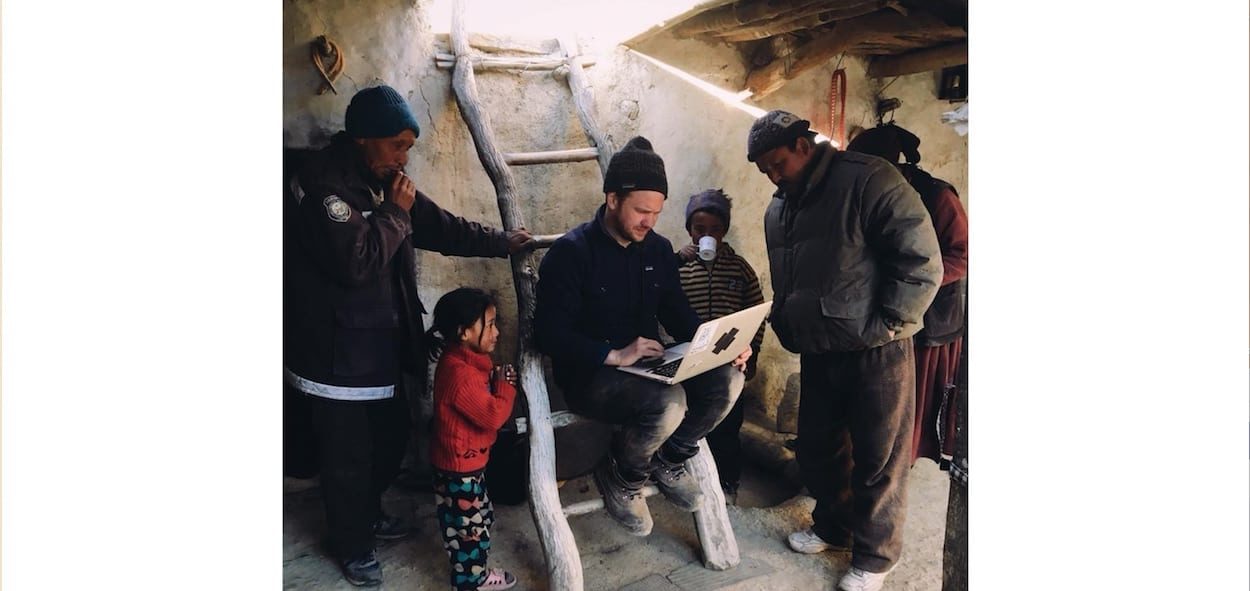

It was a communication adventure – apart from Samphel nobody spoke English. So when the verbal language failed it was necessary to talk with hands and feet. Thanks to that a unique atmosphere was created on the set. We laughed a lot and became closer to each other. I was surprised how similar we resemble each other. Maybe because of this the actors were more relaxed and natural.

Was Jágr on board from the start or did he think you were a crazy bunch of Czechs and didn’t realise you were about to make a warm, wonderful film that was going to pick up awards?

The head of the foundation discussed the topic with Jarda Jagr through his close friend and honestly he didn’t pay much attention to it. Reportedly the video amused him and he’s about to answer but his hockey career is going through hard times now and he has many more important things to deal with.

Did the story come together in the edit?

No, I made the script up before leaving for Little Tibet. I wanted to be sure that we knew what we were shooting and where we were heading to. It would have been too risky to make the script up on the spot.

Did you have lots of surplus footage or had you mapped out the narrative and storyboard fairly tightly before the shoot?

I was not that specific in my preparation. There was a script but not a storyboard. I think that in this kind of project the storyboard only kills the openness towards various situations and the dynamics that can arise during the shooting. So there were some basic scenes given such as Lobzang’s training, sewing the number or praying to Jagrlama but for example the scene with the cellphone came up during the shooting.

What were the main challenges of the production and how did you resolve them?

As I’ve mentioned before, the biggest obstacle was communication. But also the cold and the altitude. During the first days it was really exhausting to climb a small hill due to these factors. The crew consisted of three people only – the DOP Dusan Husar, AC Ludvik Otevrel and me – so any transfer and manipulation with the equipment was as demanding as all-day jogging. However not all the production issues were more difficult than usual – for example it was much more simple to ensure the locations.

Did you end up loving Tibet or rather pleased to get on the plane home?

The first option, absolutely. The locals live in difficult conditions but despite that they are very obliging and always in a good mood. It is probably also influenced by Buddhism which is the dominant practice in the village. The inclination towards solidarity and caring for nature wins over materialsm in every respect. I think we have a lot to learn from them.

Anything else you’d like to share?

For me this project was also a confirmation of the fact that a film often lives its own life and it can influence things beyond what the creators intended.

About a month after the release of the film, the director of the foundation told me that Lobzang – the main hero of the film – is in the spotlight of the whole village and everyone started to call him Jarda.

Until that time he had been perceived as a naughty child with no interest in school. Now he’s a hero.

Norboo, the director of the school, wrote to me saying: I realized that we evaluate children only as good or bad according to their study results. But if someone is talented in sport it is understandable that he won’t be so interested in studies. I’ve completely revised the way I think about children and I will try to reflect it also in evaluating the students at school.

For me that’s a clear message that videos have the power to make change.

Apart from making wonderful charity ads what else do you create?

I like short formats of any kind. It doesn’t matter if it’s a charity commercial, a music video or a fashion video – the only thing important to me is that the project resonates with my soul and is in compliance with my creed. In these cases I love the process more than the result.

LINKS