You guys are masters at juxtaposing the band’s performance into parallel sub-plots. Spectacular narratives unfold around the artists, and in your latest video for Arcade Fire the landscape plays a major supporting role too.

The framing of the pylons, the angles of the power lines, the children playing in burnt out relics, all contribute to a feeling of disconnection and dystopia. What was behind your decision to use these particular landscapes?

The overall ambition was to make a video that felt magical but also had a darker vein running through it. We wanted to create a parallel world – something both familiar and strange. And rather than tell a story we wanted to capture the mood of this world.

Please tell us the creative process of writing the storyline for Everything Now. Was it fuelled by discussions with the band, with the lyrics or was it solely your interpretation of the track?

The track is both anthemic and melancholy. It’s a strange mix. A lament that is also uplifting. So trying to create something that worked for this contradiction was very important for us.

It was also a collaborative process with the band. We spoke on the phone repeatedly in the short time we had to prep. The idea started out as a video about all the different phone calls taking place in America at one moment in time. This evolved into us thinking about the infrastructure of a country and the corporatisation of a country. And then this started us chatting about the distance between adults and children.

To what extent was the framing and the pacing of the visuals pre-planned – did you have detailed storyboards that you stuck to? Was everything shot in camera or were some of the effects created in post?

Almost everything was pre-planned and storyboarded. A lot of the scenes required either art direction or post FX. There were huge set builds like the crashed satellite which was all in camera. But even a scene like the two children with the trolley under the pylon required us to build a cement floor in order for them to be able to swing the trolley round.

We also had an extremely short post schedule so we had to make a pretty tight plan with MPC with regards to how many shots would need post.

In terms of the edit, certain shots were planned for specific moments of the song, like the opening shot. But the majority of the edit was very open. We shot 27 hours of footage over nine days and then our editor Sam Bould at Big Chop only had five days to cut it in order for us to deliver in time. This was the opposite with Royal Blood, where each section of the song was planned out beforehand because of the post involved.

What were the main challenges of the production?

On the one hand this is a performance video. On the other it’s a fictional world for the viewer to get lost in. A performance normally reminds the viewer they are watching a music video, which sometimes doesn’t help them get lost in the emotion of a fictional world. So we wanted to make it feel like the band were part of this world and subject to it, rather than it feel like we were cutting between band shots and then some cool visuals. It all needed to add up to create the mood of this magical parallel world.

We love love Lights Out for Royal Blood too which is a phenomenal feat of VFX and story-telling. Do you both think in “effects” when you’re creating narratives?

We usually start with a concept. Then we discuss how we’d like to achieve it. Early in our career we were very into the feeling you get from doing things in camera and the tone or feeling that gives you. But then we began to experiment with post and found that post offers a whole host of different textures too. With Royal blood the key thing was to shoot all the elements needed in camera (all the people in the different walls) but then put these elements together in post. That way the VFX have a tangibility. It feels satisfying because all the lighting and angles are right, it’s just the physics that is impossible.

How do you operate together – do you both work on the same task simultaneously or separately. Do you have different skill sets?

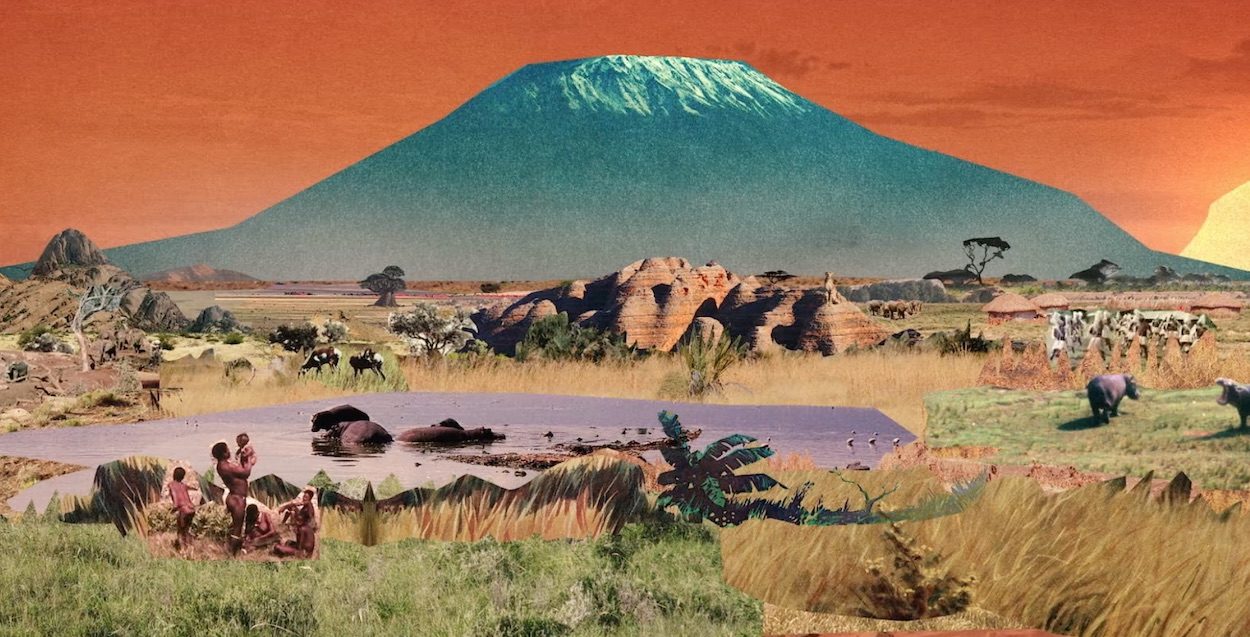

On Arcade Fire we had to split up for a few days. One of us filmed the band in Death Valley while the other prepped the second part of the shoot in South Africa. We sometimes operate multiple cameras on set and will be responsible for slightly different areas of the job. Often simply because of time we have to shoot simultaneously in order to get everything we want in the day. The main thing is that we’ve planned and prepped the job together so that our heads are in the same place.

Your recent ads for Finish and Mailchimp are distinctively art directed in clean lines and palettes with whacko scenarios. Being former creatives do you contribute to the creative ideas of campaigns?

We know all too well that the process of getting scripts past a client can be tricky. Agencies often come to Riff Raff when the script isn’t entirely locked down and they want a director who pushes the idea further. As a director you sometimes get more leeway than the creatives, which means you can help the creatives get some of their more original ideas through.

Both Finish and MailChimp were interesting because they were quite open. For MailChimp they challenged us to do whatever we wanted. They said it should be to do with words that rhymed with the name MailChimp but were totally open apart from that.

We wrote around thirty scripts for them and they consistently pushed us to go stranger. And they were the ones who decided to remove any branding / endline from the ending. It was quite a tough two month pitch process to get to the final three scripts but making the films was then extremely smooth.

Do you have a special relationship with a post production team where you plan out what’s possible or, rather, how to create the impossible?

MPC do all our post and have done for almost our entire career. They’ve really invested huge amounts of time and resources in our projects and we’re very grateful for that. We always meet with them throughout the project, starting very early on, and it’s by listening to them that we’ve learned about what looks good and what doesn’t.

Is there anything else you’d like to share?

We decided we wanted to do a documentary because that seemed like quite a different area to our usual work. Could we introduce something a little magical into something factual. It’s a two-minute music documentary that will be out around October.