You’ve been packing them in lately: brilliant films for Naughty Boy, Parisi, nolax and now this Nike series which is an interesting grittier detour from the usual legging-it-for-well-being films, so please tell us about this first…

The shoot was intense and amazing spanning Moscow and Istanbul where we tried to keep up with five young ‘influencers’ – photographers, models, artists, fashion designers and singers – to shoot a “day-in-the-life-of” that conveys the energy, pulse and grit of the cities they inhabit.

It’s really exciting to have been part of making films that position Nike in this gritty urban context, a different move for the brand I think. For me as a director they came from a place that is really intrinsic to the way I work – instantly connecting with a location, with individuals, and telling their story both through captured reality, and an injection of surrealism that moves the story out of the mundane and into the inspirational and poetic.

Did you have everything pretty well mapped out before you began the shoot?

In short, no. There was a rough outline based on Skype calls with the influencers, but the actual scripts evolved there and then. The more I work like this I’ve learnt how locations play such an important role in shaping a story especially with something like running at the core of the concept where the subject moves through multiple spaces. We had one day prep per film, which is tough, but I guess the restrictions add something to the film. I do love the challenge and having to think on the spot and react to the limitations and discoveries there and then.

Nolax looks as if it was very complicated to shoot and create – was it? What were the main challenges?

The brief was super broad. nolax is a company that supports entrepreneurs and start-ups. I was basically given a blank slate to come up with a sequence of interlinking visuals that would convey the preciousness of the spark of creativity, which drives start-ups to succeed in new areas. I loved the opportunity to come up with various set-ups that would create a driven and engaging narrative. These ideas are about dreams and I wanted to bring in visions that I’ve had in dreams, those unreal moments that can bring magic into everyday life.

It was tricky realising so many scenes in so little time, and finding characters who would make it all come to life. Street casting is one of my recently discovered joys as a director. I wondered around this little town in the highlands of Switzerland, and came across some kids hanging outside the local art school and luckily we found those faces that would make the film distinctive.

Does the process of making music videos inform your work as a commercials director?

I’ve learnt a lot from doing music videos, they train you to be able to tell a story in no time at all, to take a stimulus and interpret it into a strong innovative visual concept. While you might not always have the same level of freedom in commercials, you can definitely bring elements of this into every job. I also always find that when receiving briefs you need to deconstruct the narrative given, and reconstruct it with your own visual language and personality in order to make it yours.

However, with both music videos and commercials you have to be ready to kill some of your darlings, reject previous ideas, restart, re-write. You can’t be precious. You need to get to that kernel of what differentiates this idea from everything else you’ve seen or come across.

Parisi is powerful and mysterious, yet simple. Please tell us how you evolved the idea for this script. Were there more complicated ideas you shelved for this simplistic approach?

Parisi evolved really from a strong response to the music itself. There’s this amazing riff that runs through the whole track, and to me it sounded like some sort of slave spiritual, or jail crew anthem. This was before the track had any vocal element, so the riff was even more central than it is now. There’s a heavy embodied movement to the song, that loops, which to me felt like a trudging collectivized sound that emanates from a group of people, who are lost and downtrodden, and seeking elevation through sound.

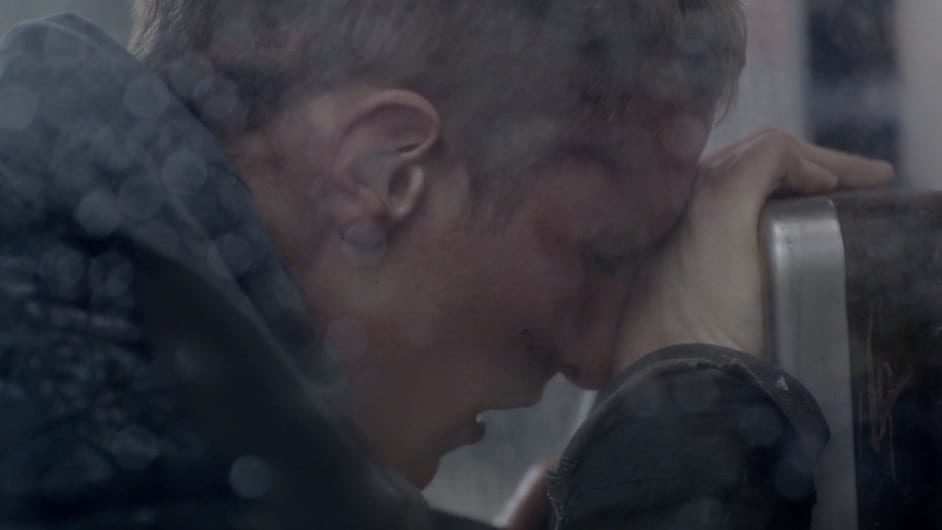

At the time of course, and still now today, the refugee crisis is raging throughout Europe, and it felt fitting to contemporize the spiritual with the idea of a dispossessed body of people moving through the no-place / every-place of northern Europe. A cold winter light, a bleak and generic setting in the mist.

The looping of the song is echoed in the looping of the action – with a repeated choreography and the return of the bus at the end, to make their journey unceasing and hopeless. The hope really comes in through the communality of their actions together, the fact that they are individuals is reflected in the syncopation of the choreography, they don’t move as one, but they are united.

I’d seen the amazing documentary, Fire at Sea, recently and some of the movements in the choreography are based on movements of the refugees during harrowing scenes of desperate prayer.

What were the main challenges of the production?

The main challenge was the delicacy of the subject we took on; that of refugees and migration. I hope that it doesn’t come across as trivialization. It was a really fine line to tread, and I had lots of discussions about how to realize it, from styling to choreography, photography to location. The generic nature of the setting elevates the action into the symbolic and metaphorical – I didn’t want to position the piece as being a reality or documentary. The syncopation of the choreography breaks the stylization enough without sacrificing the emotional impact. Even the choice of lenses was important; they are arguably very aesthetic, they add a weight and cinematic gravitas that elevates the subjects again into the symbolic.

My production company in Paris, Sovage, were an incredible support throughout the project, and without them the film wouldn’t have gotten off the ground. It’s vital to me to work with producers and DOPs who are able to bounce ideas around with me, especially with a subject as contentious and difficult as migration.

Naughty Boy was a completely different approach to Parisi – a short film about skateboarding in Uganda, a subject we wouldn’t easily have connected with Naughty Boy. How did this video come about? What was the initial brief?

The brief was really open, and was staged more as a response to the track rather a specific direction from Naughty Boy. There were videos that were given as references, and I worked from there.

I’d come across this skateboarding park in Uganda through some documentaries and photography and had always been moved by the story, and struck by the determination of young Ugandan kids to make a place to skate out of the mud and dust of the slums. The riff of the track summoned sunshine to me, so it seemed natural to bring in this story, and an amazing opportunity to use the mechanics of a promo to bring more awareness to the skate park, which is always in need of donations to keep it going – which is something we were able to contribute to through shooting there.

On location the film morphed from being a cinematic documentary, to following one young kid – Trinity – over a day. We captured the energy of the young people, and the transformative joy that skating brings them. The park has had such an impact on crime rates, getting kids out of the rut of stealing and focused on physical activity.

What is next for you?

I’m currently prepping a short film ‘Land’s End’, which is generously being funded by Creative England and that I co-wrote with my wife, Natasha Hoare. It’s a coming-of-age story set in a bleak, but lyrical world on England’s south east coast. After spending some time away in Europe I’m excited to return to the UK and find a new production home to direct commercials, branded content and music videos.

LINKS

CONTACT: benstrebel@me.com