Were you born and raised in Africa?

I was born in a township in Zimbabwe during the liberation war. We saw a lot of things that perhaps children shouldn’t. Everything around us was extremely raw, sometimes despairing, many times inspiring and every feeling in between. I managed to get a scholarship at a top private school, which is where my passion for theater was really nurtured. Going to a private school with super wealthy kids, while during the holidays living in an overcrowded home where finances were often short, helped to develop this attitude that I had to excel at whatever I did in order to have a voice in the world. It also helped develop a sense that you cannot step backwards or cower at anyone based on material things. Be proud of where you come from, because those are the things that will define and separate you as a filmmaker.

My upbringing played a massive role in defining the kind of filmmaker I want to become. I want to maintain a distinctly African aesthetic while telling stories that cross cultural, ethnic and racial barriers.

How did your knowledge of filmmaking evolve?

For a long time, I tried to shy away from my African heritage because I kept being told no one wants to do African films and Africa films won’t travel. After living in LA for eight years and having done my first studio film, I found that the only way I was going to stand out was by bringing my African heritage and aesthetic into my work.

I learnt that from watching people like Alejandro G Inarritu, Mira Nair, Alfonso Cuaron, Amma Asante, Fernando Meirelles, Guillermo del Torro and the indomitable Ava DuVernay, who brought in their unique aesthetic from their backgrounds and cultures into mainstream films. Films like Children of Men, City of God, and Pan’s Labyrinth were astounding. I want to do that for Africa. I look at my friend Sharlto Copley and Neil Blomkamp’s District 9 and I feel they really did something that encouraged me as an African to use and explore my African heritage in whatever film I’m working on. That film crossed boundaries in so many ways and that’s where I want to be as a filmmaker.

Please tell us about making One Source for Kuli Chana…

The biggest challenges were getting all the artists together in one place and trying to shoot in a foreign country with a tiny crew, which consisted of a director, producer, DoP, camera assistant and production manager. We then had helping hands on the ground to help carry gear, etc, and amazing local fixers who made it happen against the odds.

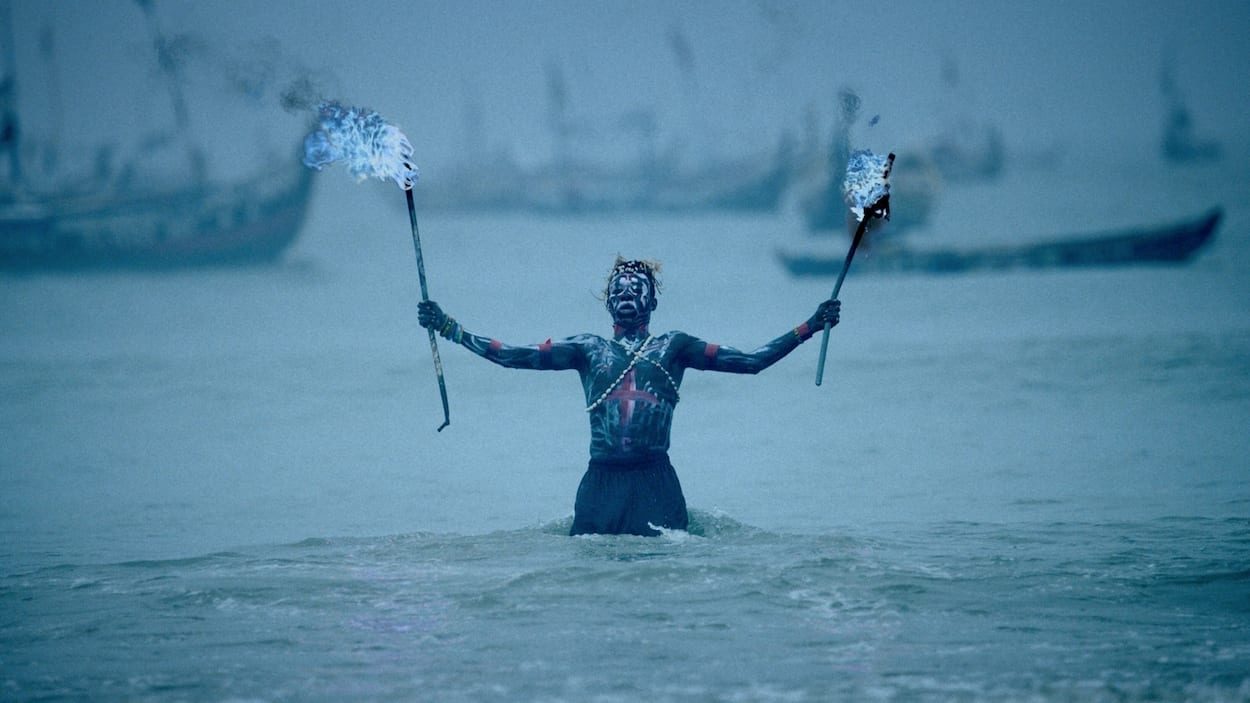

Both those challenges actually helped us, forcing us to be creative with what we had. The attitude of Africa – “make do with what you have” – really kicked into high gear and I feel it’s the reason the film became so immediate and visceral. We moved at a rapid clip to get the shots and did not overthink anything. Everyone had to jump in to make the shots work.

Throughout your work, each frame is an extraordinary event or location. What is your process for choosing your shots list?

I had put together mood boards of shots and locations I’ve always wanted to shoot. It’s a collection of images I’ve kept for the last 14 years but have never had the liberty to shoot because of the restrictions forced on us in advertising.

I wanted the artists and people of Africa to be front and centre, in their full passion and joy. When this job came up, Native VML and Absolut both encouraged me to do whatever I felt would make this film stand out and be proudly African in every facet.

We found locations that people shy away from and juxtaposed these amazing musicians and dancers against those locations. We used whatever we found in the location for art department and also for wardrobe. For example, in some shots we picked up tufts of grass and tied them to pith helmets or fallen leaves and glued them to clothing then put them on the dancers. I really wanted the film to feel like it was showing Africa to the world from the inside out, in all its glory.

What’s your camera and lens of choice – especially the kit you used on One Source?

We had an Amira camera package, with 15,5-45mm Alura zoom, 45-250mm Alura zoom, and 35mm zeiss 1.3 super speed prime.

For most of the night shoots we used the 35mm zeiss prime. I love the shallow depth of field it gives you, while still giving a sense of geography in the background. Because we had little lighting, it became our main go-to lens.

I love the efficiency of the Amira and its light weight, which allows you to move quickly. We shot most of the film handheld because I was keen to work instinctually and capture the passion, movement and mercurial nature of Africa. Dollies, cranes etc would have hamstrung us. Things happen so quickly and we wanted to be able to capture everything. My DoP Rory O’Grady was one of the stars in making this film.

We worked with available light for 90% of the shoot. Thankfully Ghana always seems to have this natural scrim, which helped a lot. We loved the flat, soft light. In post, I did push the highlights in the skin to get that kick in the dark skin tones.

The lighting package consisted of 2 x 1×1 LED panels; 2 x Red heads; 1 x Blonde; and 2 x light boards to bounce lights. And a lot of car lights, with red and blue gels on them in the night street scenes.

You have commercials and even a feature film on your reel – will you pursue making music videos (we hope so).

I’d always wanted to do music videos but I wanted my first one to really define the visual world and aesthetic I wanted for future projects. I will wait for the right artists, who are unified to push the boundaries as Khuli Chana was on this project. The song also has to be right. I was fortunate that Khuli allowed me to produce the song with him, which made a huge difference in really taking ownership on the project and having the freedom to express myself. I’d love to do some international projects. I’ve always dreamt of working with people like Coldplay, John Legend and Mumford & Sons to make visually powerful videos shot in Africa.

What are you next working on?

I’m working on a few more commercials and in 2017 I will finally be shooting my passion film, Riding With Sugar, which will take the visual aesthetic of what we started on the One Source project onto another level. I’ve tried to make Riding With Sugar for the last 14 years.

What I like about that project is that it takes place in the varied locales of Cape Town, from the upscale Camps Bay to Mannenberg and the townships of Langa and Gugulethu, to everything in between. It’s a great opportunity to tell a human story, a love story, while taking advantage of a visual language that is different from the vanilla or sterilised version of Africa that Hollywood likes to show, which is often a very different reality to what’s actually going on the ground.

Anything else you’d like to share?

I am excited about Africa, being African and really being part of the solution of pushing African film and stories to the world, without pandering to the lowest common denominator. I do believe Africa is rising and there is a creative tide on which we are now afloat. If we focus on telling our stories, our way, without losing sight that emotions are universal and bringing high production value and high quality craft to those stories, it’s only a matter of time before the world starts demanding more of our stories and our perspective. After all, this is the birthplace of humanity and there are over 1.2 billion of us… There’s a big market.

LINKS

Follow the One Source project at facebook.com/AbsolutSA or with #BeAbsolut.

View more of Sunu’s music videos and commercials here