A brief account of your journey which led you to becoming a digital artist please and what was it about CGI that appealed to you.

I studied Critical Practice at Brighton, then went on to Escape Studios in London to study Visual Effects. Since then, I’ve bounced between art and commercial animation work. One pays the bills, the other is where the fun experimental stuff happens. My commercial work takes in realistic 3D visual effects as well as more traditional 2D animation. Working in commercials as opposed to film means that I’m constantly jumping from one technical challenge to the next, adapting my styles and practices to suit, which is an amazing background to explore CGI and animation as it means I have a good overview of current technologies and approaches to the digital moving image. The toolset is amazing, and if you disregard the steep learning curve, the potential for creation is unrivalled – you are a sculptor, a writer, a cinematographer, a choreographer… all from the comfort of an ergonomic chair.

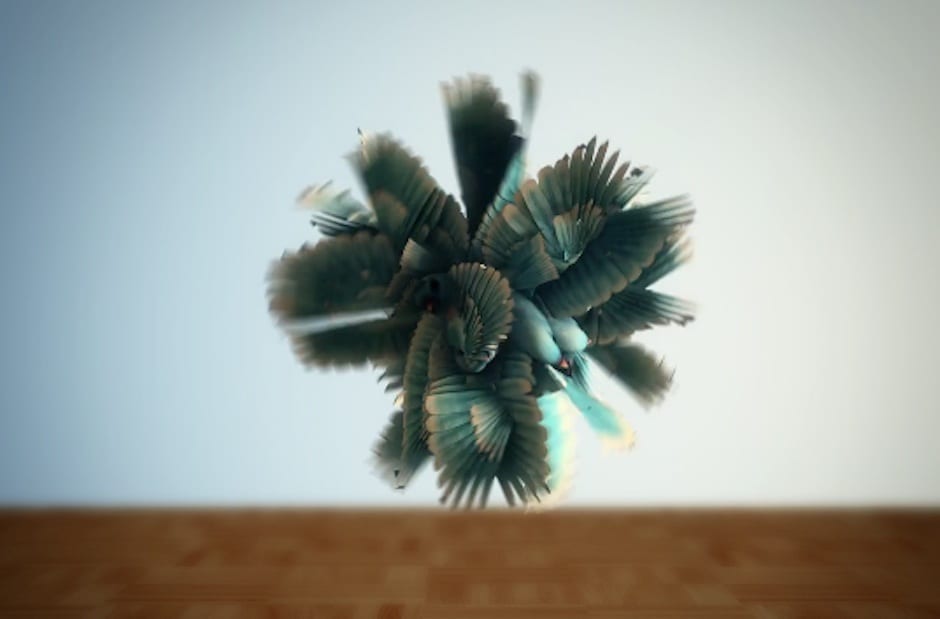

What were the challenges of the brief set by The Photographer’s Gallery and Animate Projects for Spherical Harmonics or was it an open creative brief?

The brief was for their digital wall and the commissioners really wanted to explore the intersection between photography and animation. My first port of call was how current digital techniques dovetail with traditional photographic practice, and how CGI especially can create images and worlds that extend the representation of reality into more ambiguous territory.

Please tell us about your ongoing series, Assets.

Assets is a series of images that present digital readymades, as found online in 3D object warehouses. These sites – like Turbosquid – have vast collections of virtual objects that range between amateur video game assets to professionally crafted architectural models with everything in between. Digital humans and animals sit alongside modernist architecture, weaponry and cartoon characters. It’s a fascinating resource that brings up all sorts of themes to do with iconography, indexes and ideals.

How has the visual reference library of CGI evolved amongst digital artists? Fifteen years ago the digital world was struggling to create realistic water or human skin textures. What are the current benchmarks of cgi excellence and which areas do you feel need developing?

With every new special effects blockbuster – or each Pixar or Disney film – a new area of physical simulation is refined. Life of Pi perfected water, Pixar’s Brave pioneered hair, World War Z raised the game with regards to crowd simulation. The funny thing is that what seems to us now to be ‘realistic’ may well seem quaint and naive in ten years time, so I’m hesitant to comment on what is ‘state of the art’. Facial animation on digital humans is the holy grail of visual effects, though – the minute muscular movements and complexity of emotion portrayed in the simplest of reactions seems to elude animators still.

Advertising images from cars to kitchens to the human form are entirely created digitally to an “unrealistic perfection” and are now part of our everyday visual language. What impact do you think CGI is having on our lives? Do you think people will forever strive for an unrealistic perfection or do you think we absorb the deception on a subliminal level as part of contemporary culture?

I think that there’s certainly a creeping visual ideology being created by CG images, though most people are aware of it and have a level of distrust towards images. What interests me is our relationship to the natural. Better technology and faster processors mean that we can more directly represent nature: whether that’s natural beauty or natural disasters, what is natural is increasingly becoming engineered. And film directors all have their own way of making things seem natural. The worry is that nature starts to fall short of aesthetically refined on-screen reality.

On the other hand there is a new fantasy world created by CGI artists for music videos, film and commercials too where the special effects are the key idea of the narrative. And there is a new exciting digital beauty as in your art work. Do you feel there has been a new emotional dialogue between the viewer and CGI work over the past decade?

CGI is the sort of artform that fights to be tamed – it’s hard to understand and time-intensive to produce, so the artists that play open-endedly are few and far between. That said, there’s a huge culture of digital experimentation that is still in its infancy, though this culture is not without it’s limitations: there’s a bit of a battle to liberate digital techniques from the commercial world as it’s often only there that artists get the incentive to experiment. Another problem is the preponderance of nostalgia in contemporary moving image work – a lot of animators spend time trying to ape the craft of past arts – puppetry, stop-motion, cel animation and so forth. I think that’s symptomatic of an uncertainty over the characteristics and strengths of the digital image.

Do you ever introduce intentional imperfections like a good Persian rug that has a flaw purposely woven into it?

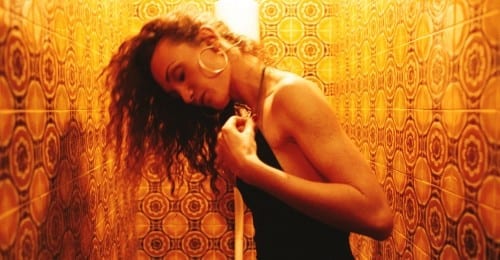

I find that I don’t need to as CGI only ever sabotages perfection. That is the singular defining paradox of CGI images and the theme runs through every aspect of digital image making. For example, the bathroom tiles in Spherical Harmonics are perfectly flat. And no matter how far we’ve come with industrial techniques, no bathroom tile is ever perfectly flat, despite the best efforts of engineers and product designers. So CGI has won, but also lost – it’s too perfect and not perfect enough.

We’re assuming you spend days locked away rendering and manipulating as is the want of the CGI artist – is this the case with you and how would you describe your working space?

When I’m working on a project it is incredibly intense. Time is of the essence because as soon as you stop animating and constructing, you need to start rendering (getting the computer to do all the complex calculations that create the final image). If there’s a complex 3D scene that you need to review the next day, you have make sure that there’s enough time overnight to render the scene for review in the morning. There’s this delay between working and seeing what you’ve made that can be debilitating, but is more often just exhausting! There are computers (and CG artists!) all over London that haven’t been shut down for months!

Where do you think the computer graphics industry is heading? And who is leading the way – the scientific engineered world or digital art and graphics?

The CGI industry has the commercial impetus to push the boundaries. When you’re talking about hundreds of millions of dollars in profit, there’s real incentive to develop new and groundbreaking tech. Graphics card manufacturers are catering to the escalating needs of movie studios to produce more complex scenes in shorter time spans at higher resolutions. So tech follows art in a lot of senses. Scientists reap the rewards of so many technical leaps pushed through by the demands of the entertainment industry.