At what point were you brought in on the creative process?

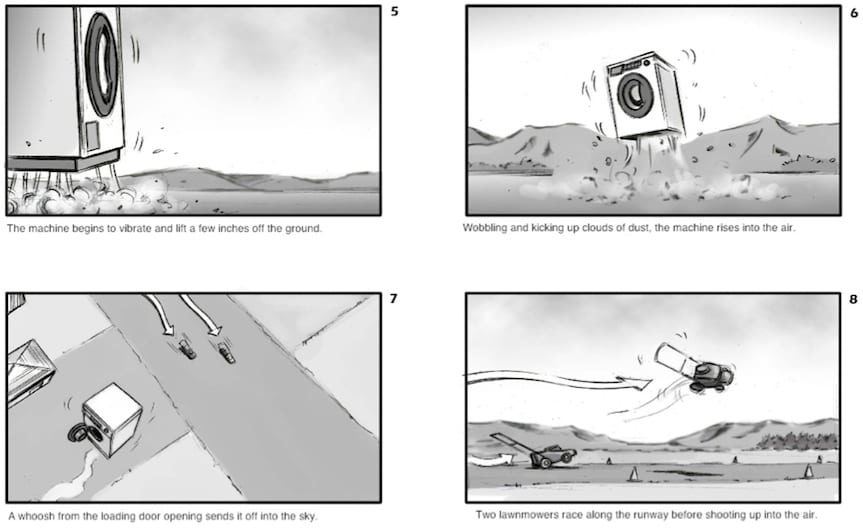

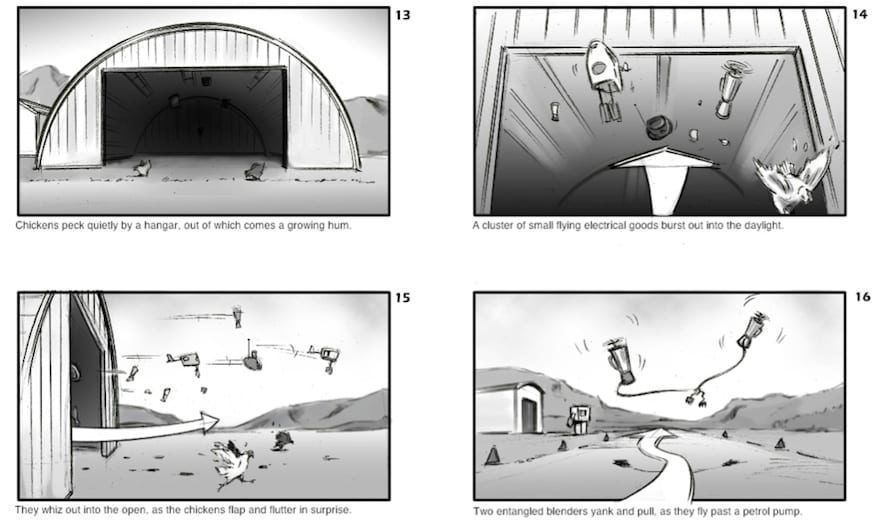

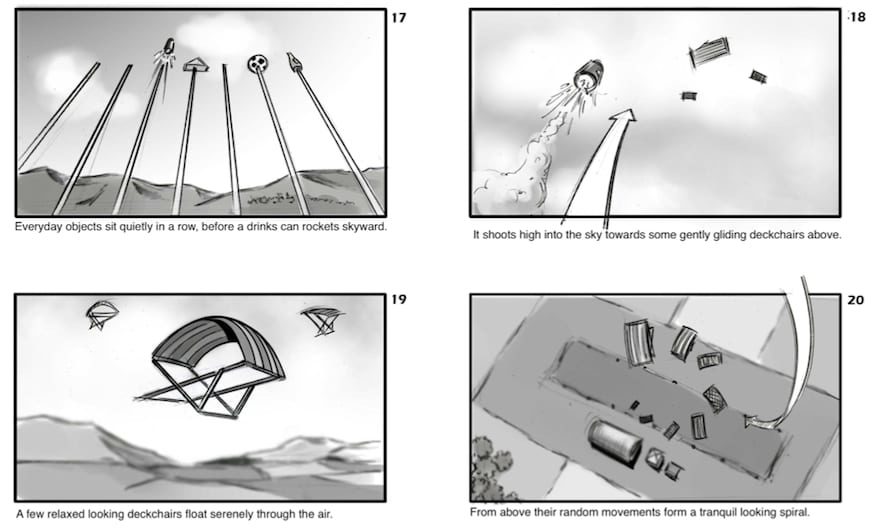

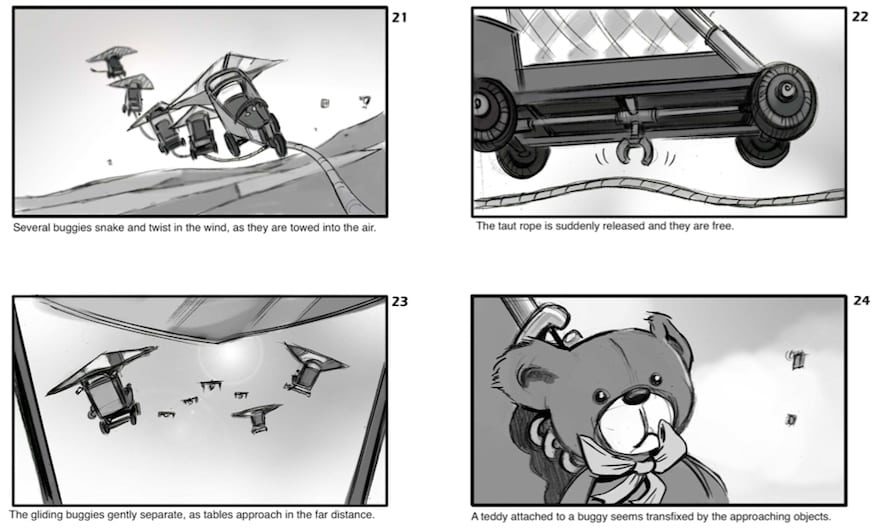

I saw the script early on and the whole thing seemed a bit weird especially as no one knew what or who Avios was. The idea had come from the agency, who explained that Avios was a new reward scheme that allowed people to buy just about anything to earn flights. The idea that everyday objects could fly was already established, but how they would and what the tone of the spot was going to be was still very much up for discussion.

What was the brief from 101?

Augusto Sola and Richard Flintham at 101 had come up with the concept that ‘Anything Can Fly’ and our brief was to make it happen. They had already discovered Rupert, but with no experience of commercials or film special fx, no one knew if he was going to be able to deliver what we wanted. I don’t think he really understood what he was getting into. But we visited him in Devon to see how things were progressing and immediately I knew we’d found our man. There was something in his commitment and conscientiousness to get it right and do it well, that impressed us all and if anyone was going to be able to make a washing machine fly in just a few weeks, he was.

The end result is a lyrical beautiful film – was this always the desired tone?

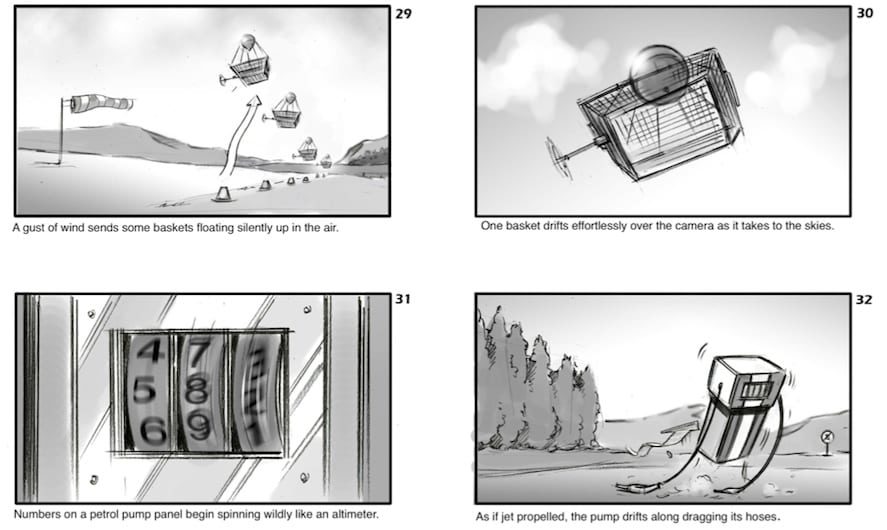

The idea was always to make a beautiful film, but it was only when we saw the various objects actually flying did we all realise what unexpectedly elegant and magical things they were. So when it came to the edit and finding music, it was a case of looking for something that brought out those qualities. We approached Peter Raeburn at Soundtree who came in with an array of tracks that he’d tried against an early cut to gauge our opinion. The intention was for Soundtree to compose a track, but he left us the tracks and, of course, we went away and started editing to them. One immediately stood out and it became the basis of a track that Peter and the recording artist modified and developed into the final piece.

What camera did you use? Were any cameras airborne too? Digital or film?

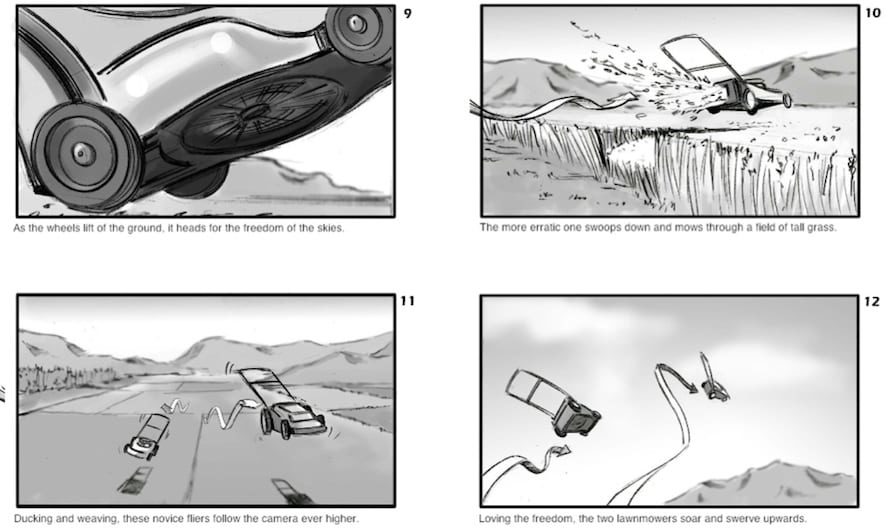

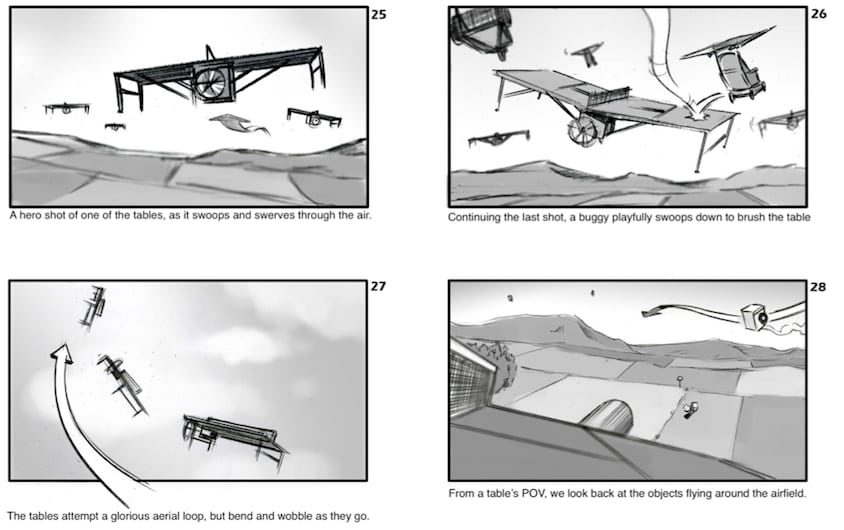

I wanted the audience to be able to fly with the objects, so this meant using a form of helicam that was incredibly stable and could get us very close to the objects as they flew. This meant shooting digitally. So for the sake of consistency, everything else was shot digitally and that allowed us a lot of cameras that simply wouldn’t have been possible if were shooting on film. For one lawnmower shot, we had a video camera flying above, an Alexa on a steadicam chasing the action from the ground, another on long legs sniping from a distance, a go-pro attached to the lawnmower’s side and a raft of Canon 5Ds in varies people’ hands including one directly in the path of the lawnmower as it took-off. It seemed like overkill at the time, but then we didn’t know quite what was going to happen and how many takes we were going to get before a crash or a technical problem.

Did you use only natural daylight?

We only used natural light, even though the day light hours available to us were greatly shortened by the surrounding mountains. I wanted it to feel charmingly amateur and filmed for real with no obvious polish or crafting. We were then blessed with three sunny days, though grey and overcast would have been just as welcome. That said, it wouldn’t have been nearly as beautiful, so we got very lucky there.

Did you ever consider creating the spot in post?

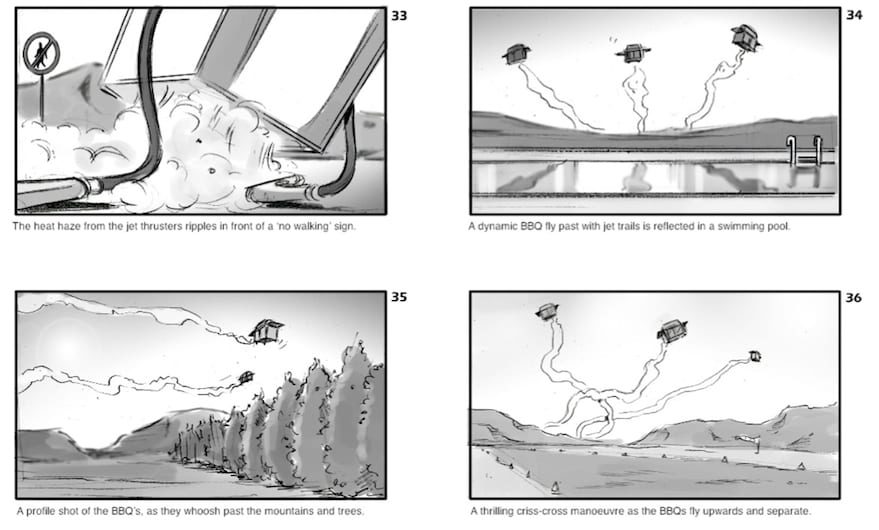

No. However, at that stage we didn’t know how we were going to get the objects off the ground or how they would behave in the air, or even if any of our ideas would be possible, but we did know that doing it for real was going to produce some surprising, if not surreal images and so that was our approach from the outset.

Were any of the appliances jettisoned? How many machines actually got to fly?

It would be easy to write a long list of objects that we wanted to fly but the real issues were what was possible. Rupert, along with professional remote control display pilot, Jason Platt, struggled with a whole range of things and I think in the end they discovered that just about anything was possible, it was just a matter of time and resources. So we chose the things you see in the ad and they went away and did their thing. And with a small team of friends, working crazy hours over a couple of weeks they achieved what no respectable special effects company was willing to take on.

It must have been rather an unpredictable shoot. What were the disappointments and magical moments?

There was a huge risk factor on the shoot, in that we were filming in the mountains with only a few hours of direct sunlight available to us every day, we had a limited number of flying objects, none of which were replaceable and the steep valley was prone to strong northerly winds. This was a real concern because the slightest breeze would make the objects uncontrollable in the air.

On top of that, one of our main cameras was to be flying around on a miniature helicopter rig. So, any mid-air collision was going to be devastating. Throw into the mix the fact that the English pilot flying the objects didn’t speak Spanish and the Spanish Helicam operator didn’t speak English and you would expect everyone on set to be pretty anxious.

But, it’s amazing what the sight of a flying washing machine can do to people’s moods. The moment the flying started, everyone either laughed or stood there open mouthed in wonder. And with clear skies, almost no wind and only the occasional crash, the mood remained relaxed until wrap.

Where did you choose for the location and why?

We wanted fine, stable weather, access to a good film centre and a beautiful airfield location. So, we decided on Barcelona as a base and began searching in the nearby hills and surrounding countryside. However, airfields, for obvious reasons, tend to be quite boring and flat and our search became wider and wider, until eventually we found ourselves at an altitude of 1000m in the middle of the Spanish Pyrenees at a tiny airfield where only microlights or two-seater planes could land. It was certainly remote, hundreds of miles from Barcelona and a pain to get all the equipment to, but absolutely beautiful and a great backdrop for a film about everyday flying objects.

You shot Sony Foam with 101 creative director Richard Flintham when he was at Fallon. That had some unexpected moments too didn’t it?

Foam was another beautiful and bizarre experience conjured up by Richard, along with creatives Sam Akesson and Tomas Mankovsky. It was similar to Avios in that none of us knew exactly what was going to happen and everybody took out their cameras and mobile phones to record it when it did. It also involved a crash, not a washing machine or BBQ, but a people carrier driving us all back to the hotel at night after the first day of a 7 day shoot. We all emerged from hospital several hours later with an array of imbedded glass fragments, fractured ankles, internal bruising and a sense of shock that we were all still alive. Hard to forget moments like that. Anyway, we headed to set for breakfast and carried on.

LINKS: